Course:ECON371/UBCO2010WT1/GROUP2/Article5

Back to

Group 2: The Environmental Impacts of Natural Gas Extraction

Article 5: Marcellus air impact uncertain

Summary

On October 19th, 2010, the Allegheny county's Air Pollution Control Advisory Committee met to discuss the possible impacts of natural gas extraction on air quality. The Group Against Smog and Pollution, GASP, claims that natural gas extraction releases ozone. However, Allegheny County health officials inspected the three Marcellus wells drilled in the county and found the amount of air pollution to be low enough for wells to not require permits under county legislation. The county has yet to decide whether air quality monitoring is needed.

Analysis

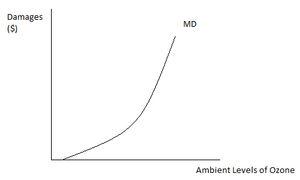

It appears that damages caused by ambient levels of ground-level ozone are fairly well understood. Ground-level ozone is the main component of smog. It has many health effects, including irritation or inflammation of the respiratory system, reduced lung function, or aggravation of chronic lung diseases such as asthma. At low levels (Air Quality Index 0-50), no health impacts are expected, as per the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency ([1]). As the levels of ozone rise, sensitive people will be impacted first. As concentrations of ozone reach a high level, everyone's health will be affected. This increasing marginal damage is shown if Figure 1.

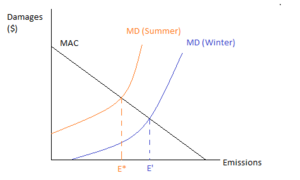

However, in order to regulate the ozone emissions released by the natural gas industry, the link between emissions and ambient quality must be understood. This is difficult due to the fact that chemical reactions of various pollutants can produce ozone in addition to that released by natural gas wells. These reactions are facilitated by sunlight, and thus contribute mostly in the summer months. As such, we expect to see seasonal variations in the damages caused by an additional unit of emission released by the natural gas industry as ozone concentrations reach unhealthy levels. This results in multiple marginal damage curves, while the industry's marginal abatement costs remain the same throughout the year. There will be multiple efficient points throughout the year, requiring regulations to be different in the summer than in the winter. This is displayed in Figure 2. However, this would likely increase the costs of compliance as well as monitoring and enforcement costs.

Since the impact of tropospheric ozone on human health is well understood, and Allegheny county health officials didn't refuse the fact that wells release ozone, the question is, why is this emission allowed? The federal standard for ozone, as set by the U.S. EPA, is 0.075 ppm over an 8-hr averaging time. As per the U.S. EPA website[2], "to attain this standard, the 3-year average of the fourth-highest daily maximum 8-hour average ozone concentrations measured at each monitor within an area over each year must not exceed 0.075 ppm."(effective May 27, 2008). It is assumed that the three wells in Allegheny county are monitored separately, and are each meeting this standard on their own. However, there are three wells in Allegheny county plus numerous other wells outside the county, which also affect the county's air quality, since air cannot be confined within a county's boundary. If the air flow in the area happens to direct a large portion of the released ozone to Allegheny county, in particular Pittsburgh which is known for its ozone problems, then this uniform standard may not be adequate. A better approach would be an individualized standard for each well whose ozone emissions end up in Allegheny county. In this case, air flow in the area would need to be understood. However, as the number of wells keeps rising, this policy may become expensive. Another possible approach is the establishment of a zone around Pittsburgh, in which stricter standards would be in effect. However, this may not be required as the federal standard is expected to be tightened in the near future.

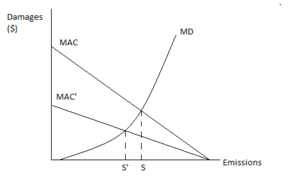

It seems that the current uniform federal standard policy has created some incentives to research for cheaper ways to reduce ozone emissions, as pointed out by Matt Pitzarella, a spokesman at Range Resources Inc., a company in the natural gas industry. He states that the industry is updating its equipment in response to reported spikes in air pollution in some regions. For example, GE’s current developments of a mobile evaporator would limit the amount of truck trips required and, as a result, decrease vehicular emissions of which are a significant portion of Pittsburgh’s ozone levels (while, also, in the long-run reducing the industry's transportation costs). With new equipment, firms may be able to lower their MAC and prepare themselves to meet the stricter standards that are said to be on the way. This idea is depicted in Fig 3.

Figure 1

on the right shows the marginal damage function in relation to ambient levels of ozone. For low concentrations, no health effects are expected. At slightly higher concentration, only sensitive people will experience damages. A high level of ozone poses a threat to everybody's health, especially causing problems related to the respiratory system. Therefore, the MD curve rises sharply.

Figure 2

shows the seasonal variation of the marginal damage function. Due to marginal damages being higher in the summer, tighter regulation is required in the summer, as shown by E*<E'.

Figure 3

shows the current (MAC) and future (MAC') marginal abatement curves for a hypothetical company in the natural gas extraction industry. A downward pivot of the curve is a result of innovation of cheaper abatement technology. A firm that adopts this new technology will be better prepared to meet the stricter standard S'. It is expected that the U.S. EPA will soon enact a stricter standard on allowable ozone emissions by natural gas industry.

Prof's Comments

Nice. I like your careful thought on the shape of the MD curve.