Course:ECON371/UBCO2009WT1/GROUP6/Article4

Group 6: Carbon Tax in Canada

Article 4: Carbon Credits: 'Cure worse than the disease'

Complementary Reading: How to Get Climate Policy Back on Course,A Market-Based Solution to Acid Rain: The Case of the Sulphur Dioxide (SO2) Trading Program (Available on JSTOR),New Climate Plan Would Favour Oilsands,Cap-and-Trade: Recipe for Disaster, Economist Says

Summary

Premier Jean Charest wants his province to lead Canada in the implementation of a cap and trade system to reduce carbon emissions. The Premier wants to establish a carbon market before 2012, an agreed upon date of the Western Climate Initiative (WCI) which Quebec, along with Ontario, Manitoba, BC, and several American states are members of. Charest presented his plan likening it to an initiative of the 1990s where Canada created a cap and trade system for sulphor dioxide. Charest credited cap and trade for successfully reducing SO2 emissions and resolving the accompanying acid rain problem. However Christopher Green, a McGill University economist is against a carbon market, and instead wants to see a carbon tax.

Christopher Green says a carbon market won't work for many reasons. First, he dismisses Charest's claim that a cap and trade system would work with carbon just like it did with SO2 in the 90s, because back then SO2 was only being generated from roughly 300 coal burning plants making a cap and trade system easier to implement and because a cheaper low-sulphur coal just got on the market. With Carbon there are too many emitters, from cars to lawnmowers and gas barbecues. Also it's not just the number of emitters but the different amounts they emit; for example Alberta's oilsands in being so carbon-intensive would make a cap-and-trade system complex. There is also not only the problem of offsets in developing countries that is a concern, but so too is the fact that such countries depend on carbon-intensive energy sources. Green criticizes the proposed cap and trade system's high prices of carbon, calling them unrealistic. Instead of a carbon market, Green suggests a carbon tax of $10 per tonne of CO2 emissions. When compared to a cap and trade system, Green argues a carbon tax will create a greater incentive for technology innovation. Christopher Green concludes by expressing frustration in the political support for a cap and trade system over a cabon tax.

Analysis

Cap-and-Trade And Carbon Tax In Brief

A cap and trade system creates a new type of property rights: rights to the property of emissions. The transferable discharge permit (TDP) system creates permits that allow the owner of said permits to emit a certain quantity of emissions. A market is enabled where prospective buyers and sellers can engage in trade to maximize their levels of emissions and costs of abatement. A carbon tax on the otherhand simply places a price on a given unit of emissions, and firms will adjust their emissions until the tax rate equals their marginal abatement cost (MAC). In not utilizing market forces, a carbon tax is more centralized in this regard.

Cap And Trade: SO2 Ain't Carbon

In 1995 the Acid Rain Program was initiated in the United States, it created a market in which a limited number of allowances for sulphur dioxide emissions could be bought and traded among emitters. It's goal was to reduce SO2 emissions from 17.5 million tonnes to 8.5 million tonnes by 2010. It has for the most part achieved this and at a fraction of the estimated cost. Premier Jean Charest has inferred that since cap and trade worked in reducing sulphur dioxide emissions in the 1990s, a cap and trade on carbon will have a similar effect in reducing carbon emissions; however Christopher Green offers counterpoints that suggest no such inference can be made.

Mr.Green reasons that a comparison between a cap and trade of SO2 and carbon cannot be made because of the differences in emitters. The cap and trade system had relatively very few SO2 emitters making it easy to administer. For instance, phase 1 of the acid rain program only had 263 polluting units, with 110 of those being coal-burning electric utility plants. Carbon on the otherhand not only has millions of emitters, but has large differences between those emitters making any potential carbon cap and trade system more complex. It must be acknowledged that trading permits cannot apply to the millions of average Canadians who emit carbon daily and as for larger emitters a cap and trade system would have to apply to industries of varying magnitude from small factories to the carbon-intensive Albertan oilsands.

The complications involved in such a cap and trade on carbon were recently reported on by the Toronto Star. In early September Environment Minister Jim Prentice announced a two-tier cap and trade system, one that would restrict emissions from Ontario and Quebec, but not Alberta and Saskatchewan. The article cites Andrei Marcu, an International Emissions Trading Association board member, who suggests that a system based on different treatment for different industries risks being too complex to manage.

In this situation the cap and trade system would be too complex because it effectively establishes two markets, not one. One market for the region of Alberta and Saskatchewan that would allow industries to continue increasing emissions, their permits would not be absolutely fixed, and trade would only be between those emitters; the other market would be for the rest of Canada, where permits would be fixed and consequently most likely be a higher price. If stratification of a carbon market was pursued, besides the increase in transaction costs to reflect the additional administrative burden, the overall effect would be a decrease in efficiency.

With the two tiers, there would be two prices, and assuming each market has the same marginal demand curve (considering CO2 is globally damaging, there is no reason to suggest otherwise), then there will be situations where buyers or sellers of TDPs in one market are willing to buy or sell in the other market but are restrained from doing so. Firms' marginal costs of production are therefore unable to be equalized, and the resulting inefficieny is a violation of the Equimarginal Principle.

Price Volatility: The Cap And Trade Disincentive to Innovate

In analyzing the SO2 cap and trade system of the 1990s, the price of permits was found to be quite volatile which could have theoretically resulted in negative impacts on any incentives the system offered to Research and Development (R&D). When the acid rain program was created the expected permit price was $1000, however as time progressed the price fluctuated wildly; from $70 in 1996 to $212 in 1999, all the way up to the $700 range in 2005 and eventually back down to a low price of $88 in Aug of 2009. Though it is difficult to attribute exact causes behind these fluctuations, the price volatility that was exhibited furthers Mr.Green's case that a carbon tax is best for encouraging research and development.

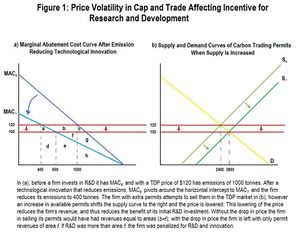

A clearer example of price volatility discouraging investment in research and development can be seen in Figure 1. If a firm was to make an initial outlay of funds for R&D and eventually produced a technological innovation that reduced emissions, the Marginal Abatement Cost (MAC) curve would pivot from MAC0 to MAC1 reducing emissions from 1000 tonnes to 400 as seen in (a). As one permit allows for its owner to emit one tonne of carbon the firm would then have 600 extra permits. In theory the firm could then sell its permits at a price of $120 and generate revenue equal to areas (a+b+d+e+f), when the abatement costs are considered the net gain from the sale would be areas (b+f). However in reality, as the firm has a new excess of permits so will the market, making the supply curve shift out, as seen in (b). To sell the permits, the firm must lower the price from $120 to $100. In lowering the price the amount of revenue generated decreases to areas (e+f); now when abatement costs are subtracted, the net gain is only area f. This is an important consequence because if the original funding of the R&D was larger than area f, the firm will actually be worse off then if it didn't invest.

Volatility in a cap and trade system could come from numerous sources, a carbon tax however does not offer such unpredictability. One source for price fluctuation in a carbon market could result from few buyers and sellers; the price will be significantly affected by their actions. Other sources for price volatility could arise from energy-demand from weather or the prices of alternative fuels rising or falling. A carbon tax on the otherhand is better at providing R&D incentives because the price placed on each tonne of emissions is enshrined in law and thus more certain. A firm can safely plan to invest in research knowing that the permit price will not change and erode any possible gains. On this point it can be seen that greater investment in R&D will be encouraged with a carbon tax than with a TDP system.

In addition to Mr.Green's objection to a cap and trade market based on its vulnerability to price volatility, Keith Johnson from the Wall Street Journal draws out the implications that would naturally arise. First in his blog, Johnson adds to Green's SO2 example by citing the price fluctuations of CO2 permits in Europe, then he proceeds to suggest that having a carbon market in the US would lead to similar speculation that occurs in other markets. Such speculation he notes would consequently negate the intended environmental purposes of the system. A possible solution would to be create some type of central banking structure that would regulate the supply and price of permits, however as the blog entry points out such a structure would add complexity and would not only increase transaction costs but interfere with the market allocation of permits.

carbon tax Vs. cap-and-trade for number of emitters?

With a large number of emitters a cap and trade model is not efficient because enforcement would be unpractical. The resources and manpower required to put this into place would be huge, making sure there are no counterfeit bills on the market, and insuring currency used matches emission levels. Without the proper enforcement framework there would be not be a large incentive to follow the rules and the policy would be useless. Also we must compare the fact that wasted financial resources would be going into enforcement of the cap and trade model. When we look at the carbon tax model however the government can more easily gain revenue shown on the graph. With this model we see the higher the population the demand curve will shift out and the the government revenue will be higher, which Mr. Green points out can be put towards research and development to further reduce our carbon intake. There is also the problem with collecting data. With a cap and trade the government relies on the companies to divulge information about their own emissions in order to set a cap. With this amount of producers it’s very difficult to prove the reliability of them all. Unlike the handful of factories for the other cap and trade which would all be generally the same size how would the government compare the emissions allowed to be let out by the average farm for example in comparison to a large oil operation in Alberta. A simple tax would better account for the different needs of these varying industries.

Revenue graph( )

)

Will we make 65% by 2050?

From 2003 to 2006 carbon emissions fell by 2.8% most of this from reduced coal and oil usage in replacement for hydro, nuclear, and to some extent wind, the lower heating requirements from relatively mild winters during this time, and lower emissions from fossil fuel production. The 2006 level of 721 million would need to decrease to 469 million, or an average of 5.7 million a year. Which is not bad when you conceder over the past 3 years it has gone down by an average of 6.7 million a year. But the amount of carbon emissions is very volatile when we look at the numbers over ten years they have gone up by an average of 11.5 million per year. From 2003 to 2006 is the only substantial amount of time in our recent history carbon emissions have ever gone down, and we cannot predict variables like winter temperatures or price of oil in the future. However looking at how inconsistent the changes have been since around the year 2000 it is unlikely 65% is a realistic estimate without at least a strong government policy along with favourable other variables like the price of oil, the general welfare of the economy and temperatures. http://www.ec.gc.ca/pdb/GHG/inventory_report/2006/som-sum_eng.pdf

Conclusion

Though a cap and trade system is more decentralized than a carbon tax, both are similar in theory; both put technical pollution-control decisions in the hands of polluters, both are market-based, and both are identical in offering strong incentives for emitters to invest in R&D. In reality however due to price volatility that is associated with a TDP market incentives are hindered and can possibly be deterred.

In light of recent examples of price volatility in cap and trade systems, as seen in the American SO2 and the European carbon markets, Jean Charest's motivations in supporting a TDP market must be questioned. It could be that the Quebec Premier is merely recognizing the international political reality that a North American cap and trade system will be eventually established and he wants his province's industries to be well adapted to the structure beforehand. Indeed Charest could even acknowledge that price volatility in permits will exist in the short-term but perhaps will be minimized with the entrance of American firms in the system. Charest could see a cap and trade as more politically paletable; taxes are almost always viewed negatively, while on the otherhand giving firms rights to emit would be seen more positively.

Prof's Comments

Your criticisms of the cap and trade may be a bit strong. Both a cap and trade and an emissions tax require some means of measuring that which is being regulated. To tax emissions, you have to monitor them. To ensure a cap is being adhered to, you also have to measure emissions. Cap and trade for each individual carbon emitter will have a high transactions cost, relative to a simpler tax. However, a carbon tax is typically implemented as an input tax. A cap and trade could be implemented in the same way. If so done, the tradable emissions permits could be held by the fossil fuel suppliers, who simply pass the cost of the permits on to us as the consumers. To the consumer, it would essentially be a carbon tax. However, to the firms, it would be a tradable permit system. Now, this is not what is being suggested. Rather, the proposed cap and trade is supposed to insulate regular consumers and put the burden on large emitters. Politics at work.