Course:ECON371/UBCO2009WT1/GROUP4/Article1

Group 4 - The Environmental Impacts of Agriculture in British Columbia

Article: [1]

Rancher Calls Water Order Attack on Agriculture (September 22, 2009)

Summary:

On September 18, 2009 the provincial government issued, for the first time, an order[2] to the Quilchina Ranch that uses water from the Nicola River for the purposes of irrigating alfalfa for cattle - instructing the ranch to stop using water for irrigation purposes. Mr Rose, a member of the ranching family who had been issued the order, estimates that the lost use of water will cost their farming business $150,000. Two other water licenses, Douglas Lake Ranch and a the Upper Nicola Band, at the request of the Ministry voluntarily stopped irrigating to support the in-stream needs of spawning Kokanee[3](landlocked Sockeye salmon).

Water limited years provide a number of water management challenges for local and provincial governments. The Nicola River, a Kokanee fish bearing stream, experienced low-flow conditions in 2009, in part due to reduced winter snow pack levels and compounded by a spring and summer of low precipitation.

Historically in the Province of BC, managing during times of drought have evoked the principle of first in time, first in right - which translates into the person with the newest water licenses loosing their water supply, and then the next junior license holder and so on until the required flows for a given stream are met.

This order issued by the Ministry of Environment to protect fish brings up some legitimate questions about compensation. First, to the agriculturalist for loss of use of water when a legal water license has been granted by the Province. Second, compensation for water storage. Throughout the Province water utilities and individual agriculturalists have developed costly infrastructure (dams) developed to store spring freshet water for use during the summer and fall - specifically to support the needs of agriculture. Using stored water, available only as a result of the infrastructure investment of a water purveyor, for in-stream flow requirements of fish raises questions of fairness, right-to-farm and compensation requirements for storage infrastructure costs. Over the years to come, these questions may be put to the test.

Analysis:

Governance Issues:

The order issued to the Quilchena Ranch sets a precedent under the newly revised Bill 25 [4] Section 9 (2) of the Fish Protection legislation ordering a farmer, during an identified period of drought, to cease using water. In the Rose case, bringing into question the value and certainty provided by a 130 year old water license.

Section 9 (2) of the Fish Protection Act states: "...[when drought conditions threaten the survival of a fish population], for the purposes of protecting the fish population, the minister may make temporary orders regulating the diversion, rate of diversion, time of diversion, storage, time of storage and use of water from the stream by holders of licenses or approvals in relation to the stream, regardless of precedence under the Water Act."

Externalities:

In applying the order option under the BC Fish Protection Act, the government must consider the trade-offs between agriculture economic considerations and those of the environment. Imposing regulations is rarely a popular action by senior government - but it can be a necessary tool to protect our environment. Due to lower water level, the number of Kokanee salmon is dwindling. There will be less salmon that will be available to fish. If there are no salmon available to fish, there will be no social benefit received fishing. In addition, the Nicola River’s ecosystem and food chain will change as Kokanee salmon die out. There are many animals that feed on Kokanee salmon that will be negatively affected. The destruction of habitat may reduce property values in nearby residential properties, reduce eco-tourism opportunities, and impact the costs of treating water to ensure safe drinking standards. The water decline, may cause a desertification problem - reducing arable land values and food production. As the climate change impacts are realized at a local level, water managers anticipate increased variability - more periods of drought and flooding than historically experienced. If the water flow continues to decrease, it may cause a serious local climate change issue later on - with the potential for long term impacts for residents in the area. The Fish Protection Act is one tool, tested by the Rose order, to deal with situations of water scarcity in BC.

Public Ownership and Fairness:

In the Rose order a number of important economic and resource economic ideas are put to the test. One question that policy makers may be concerned with is, during times of drought what tools may be applied to reduce water use to support environmental water needs?

The marginal external costs and, some may argue, the true marginal private costs of water during low-flow conditions, aren't accommodated for in the current licensing system. License holders pay an annual set fee for a volume of water.

Water in BC is "owned" by the Province. Anyone wanting to use surface water for a beneficial use requires a water license. Therefore water is a controlled resource and yet it has many of the characteristics of an open-access resource. An individual may license water giving them access to a certain volume throughout the year. Farms and urban centres have been developed based on the assumption that senior water licenses will ensure adequate water under all water supply conditions - for a set price. The application of Section 9 (2) of the new Fish Act puts into question the security of water license holders on a fish bearing stream.

Water supply does not meet the definition of a public good - it doesn't meet the test of non-exclusion (a percentage of water used by a household is sent to a wastewater treatment plant, treated, and released into the environment for use by someone else). Nor does water meet the test of non-rivalness because a percentage of water used on a lawn evaporates and is not available for use by anyone else in the system. Therefore, it seems reasonable that water is better described as a private good.

The Rose order may be an example of an unfair legislative tool. Land owners will be disproportionately affected in the application of this policy. It has been suggested that as a market based tool, in contrast to a regulatory one such as the order tool available under the Fish Act, that marginal costing of water may provides for a useful mechanism to reduce the use of water, whereby the highest and best use of the limited resource is achieved.

During a normal year, water supply provides all of the needs of a system - there is sufficient in-stream flows to accommodate fish. During drought conditions, when water is limited, external costs become significant consideration. One way to look at water conservation is by equating it to marginal abatement costs as discussed in the next section.

The Social Benefits of the Government Policy:

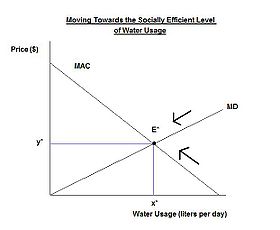

There must have been various economic and environmental reasons for the provincial government to take such strong action and strictly enforce its new legislation on fish habitat protection. By barring the irrigation and restricting the water usage of a large cattle ranch, there will be more water flowing through the Nicola River. This will in turn reduce the total (TD) and marginal (MD) damages caused by agriculture in the area such as dwindling fish stocks and a lower water level. The government is hoping that its policy will move toward maximizing the net social benefit and social efficiency. By spending more on abatement costs and curbing damages caused by agricultural water usage, the government believes that the industry will move toward the equilibrium between marginal abatement costs (MAC) and marginal damages (MD) (See Figure 1). This action is intended to increase salmon stocks and maintain or increase the water level along the river. The commercial and recreational salmon fishing industries, animals that depend on salmon for survival, and other residents who use and live along the river should benefit from the government’s actions. However, while increasing net social gain, the individual producer must face significant abatement costs.

The Costs to the Producer/Policy Alternatives:

For Quilchena Ranch, the current ban on water use for irrigation purposes has driven up cost of production significantly. On the ranch, irrigation, for which the water was being drawn from the Nicola River, allowed for the on-site cultivation of feed crops. To supplement the loss of crop, the ranch states it will need to purchase $150,000 of feed elsewhere Kamloops Daily News. An increase in marginal cost will reflect the increase in total cost. Assuming the market value of their final product remains the same, the Quilchena ranch will ultimately see a decrease in production and total revenue.

To avoid the financial hardship caused by such bans and treat the root of the issue, different action must be taken to reduce water use in the future. However, in the short term, though an unfavourable solution for the owner of Quilchena Ranch, the current action taken to increase stream flow by limiting irrigation seems to be the only option available. That is, it is the only action immediately available that may give the salmon a chance to thrive. A more realistic plan for the long term could not only lower the cost to society and the ranching business, but increase benefit to both parties. Such plans are already implemented but have not gone far enough. Ranches such Quilchena have already increased the efficiency with which they use their water through the environmental farm plan, a federally sponsored program Kamloops Daily News. To allow the ranchers to grow their feed as well as allow for sufficient flow in the river, greater incentives must be applied. Said incentives should include subsidies for businesses that increase water use efficiency as well as penalties for those businesses that do not. Increasing efficiency at ranches such as Quilchena will help treat the root cause of the problem, rather than export it to another locale. Thus, it poses to be a true long term solution; especially in a nation where agriculture is the fourth largest consumer of water Government of Canada Water Use Statistics

Prof's Comments

There are a lot of things wrapped up in this case. Fairness/equity is in there. I think a bit of careful thought about the nature of the externality and then carefully setting it out would be good. The analog to emissions is water use, and abatement is reduction in water use. The abatement cost is the lost profit from the use of water on the farm, and the damage is the lost value of the fish to society. Your figure suggests that you are thinking about it this way, but it was not clearly set out in the text. At the margin, it is the agricultural value of an extra unit of water against the extra social value of an additional unit of water for the fish. A particularly interesting element here is that the MD curve, and to a lesser degree the MAC curve is in a different place every year. In wet years, the MD has shifted down/out, water use would have to be very high before there is much damage. The MAC may also shifted down/in, if there is enough rain so that crop yield won't fall as much if less water is applied.