Course:LIBR548F/2009WT1/Gutenberg's Inks

While the inks of many incunabula have faded over time, those of the Gutenberg Bibles are of such quality, they continue to be admired[1] Only speculations about the recipes of Gutenberg’s inks remain, however, many of the components have been identified[1] It is uncertain as to whether Gutenberg purposely kept his recipes a secret like many contemporaneous and later printers, or if it was simply lost.[1]

Black Ink

Components

Gutenberg’s ink must have been among the first typographic inks.[1] Earlier inks were water-based and would not have adhered to the metal types and would have produced flaws such as smudging and clotting, unlike oil-based ones such as this.[1] It is quite possible that it is the high quality of the oil-base that preserves the ink and it has been suggested that Gutenberg based his recipe partially upon those of oil painters, who often used lead and copper in their compositions as Gutenberg also did.[1] In addition to these metals, Gutenberg’s ink comprises titanium, sulfur, and a carbon-base.[1] & Chaplin, Clark, Jacobs, Jensen, & Smith, 2005).

High Metallic Content

The high metallic content of Gutenberg’s typographic ink, which accounts for its glittering surface, is quite unique.[3] Copper and lead are the most abundant metals present in the ink.[1] Since the coloured inks are also oil-based and do not contain such a quantity of copper and lead, if any, the metals are not part of the oil-base but perhaps their addition has helped prevent fading of the black ink, which carbon compounds are susceptible to.[1]

Coloured Inks

Components

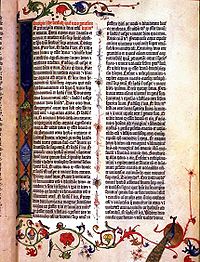

Of the seven analyzed copies of Gutenberg Bibles, the palettes consist of red, blue, green, yellow, white, and a few miscellaneous pigments.[4] The pigments found in at least six of the seven copies are cinnabar/vermilion, azurite, lead tin yellow type 1, calcite, and gold leaf.[4] The only pigment that could not be identified was an organic red ink found on four of the tested copies.[4] The ink is possibly derived from insect shells, brazilwood, or rhubarb root, such as a contemporary of Gutenberg’s used on his manuscripts.[4]

Regional Variations

Illumination on the bibles was completed after printing and prior to selling.[4] This, along with the variation in styles, leads to the likelihood that this process was completed in the same locale of the buyer, and perhaps even to the buyer’s taste.[4] Therefore, the illumination of the bibles was possibly done in many different regions in Europe, though, most in Northern Europe (Chaplin, 2005). In spite of this regional differentiation, the palettes and pigments used in the coloured inks are similar in all the analyzed books, most likely due to the limited resources available in all regions of Europe at the time.[4]

Methods of Analysis

Cyclotron Analysis

Richard N. Schwab and his team analyzed the black ink of some of the Gutenberg Bibles with a cyclotron, which uses particle-induced X-ray emissions.[1] The cyclotron accelerates and directs protons into a focused stream, which passes harmlessly as a beam, less than a square millimetre, through paper and ink.[1] Some of these protons remove electrons from atoms on the material and the atoms emit x-rays, which identify the present elements.[1] Since the beam passes through the whole material, the components of the ink were determined by comparing the chemistry of sections of inkless paper with those of inked paper.[1]

Raman Spectroscopy

This method was done in order to determine the pigments of all colours of inks. Laser light, which can focus on a single grain of pigment, was directed onto the selected area of colour.[4] The light was then collected back and transmitted to a CCD (charge-coupled device) detector.[4] This was done directly on a Bible as well as on glass slides of debris collected from the gutters of Bibles.

Ink as Evidence of the Production Process

The cyclotron analyses of Gutenberg’s black ink varied in the ratios of copper to lead, which lead some to argue that the Gutenberg Bibles were printed in six units concurrently, however, the evidence may not be enough.[4] The ratios could possibly be accounted for by environmental factors such as exposure to light.[5]

Footnotes

References

- Chaplin, T. D., Clark, R. J. H., Jacobs, D., Jensen, K., & Smith, G. D. (2005). The Gutenberg Bibles: Analysis of the illuminations and inks using Raman spectroscopy. Analytical Chemistry, 77(11), p. 3611-3622.

- Schwab, R. N., Cahill, T. A., Kusko, B. H., & Wick, D. L. (1983). Cyclotron analysis of the ink in the 42-line bible. Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, 77, 285-315.

- Schwab, R. N., Cahill, T. A., Eldred, R. A., Kusko, B. H., & Wick, D. L. (1985). New Evidence on the printing of the Gutenberg Bible: The inks in the Doheny copy. Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, 79, 375-402.

- Teigen, P. M. (1993). Concurrent printing of the Gutenberg Bible and the proton milliprobe analysis of its ink. Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, 87, p. 437-451.

Recommended Sources

Chaplin, T. D., Clark, R. J. H., Jacobs, D., Jensen, K., & Smith, G. D. (2005). The Gutenberg Bibles: Analysis of the illuminations and inks using Raman spectroscopy. Analytical Chemistry, 77(11), p. 3611-3622.

- Chaplin et al. primarily discuss the components and pigments of Gutenberg's inks, both coloured and black, in order to discern whether inks varied throughout Northern Europe in the illuminations of the Gutenberg Bibles. Though there are a few differences between all seven of the analyzed Gutenberg Bibles, using Raman spectroscopy, they determine the pigments are quite similar. An interesting read for anyone wanting to know more about the subtle variations.

Schwab, R. N., Cahill, T. A., Kusko, B. H., & Wick, D. L. (1983). Cyclotron analysis of the ink in the 42-line bible. Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, 77, 285-315.

- In this article, Schwab et al. delve into the possible reasons for the high metallic content of Gutenberg's black ink.

Schwab, R. N., Cahill, T. A., Eldred, R. A., Kusko, B. H., & Wick, D. L. (1985). New Evidence on the printing of the Gutenberg Bible: The inks in the Doheny copy. Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, 79, 375-402.

- Schwab et al. concern themselves with the production order of the Gutenberg Bibles in this article and conduct an exhaustive search for evidence in the ratios of lead to copper in the ink.