Indiana's Eugenic Sterilization Law 1907

Introduction

In the United States of America, the late nineteenth century was a catalyst for bringing about reform. When the turn of the century came about, America was experiencing transformations in industrialization, immigration, and urbanization[1]. The American population was receiving influence, in the forms or culture, ideas and people, from international borders and were not necessarily ready to welcome these different ways of life into their, otherwise, untouched American civilization.

This international change brought about cultural tensions between American peoples and “degenerates” living in American states, but specifically in Indiana. Degenerates can be categorized as those unfit to reproduce, such as mentally ill, homosexual, chronically injured, criminals, and peoples of minority cultures[2].

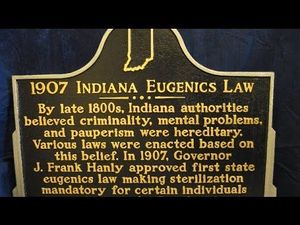

Between 1907 and 1974, the people of Indiana lived under rule of the state-sponsored Eugenic Sterilization Law. Sterilization can be defined as population control in order to regulate improper breeding[3]. In 1907, Indiana’s political regime implemented a eugenic sterilization law among society[4]. This law’s aim was to stop procreation of degenerate peoples and to promote national prosperity through elimination of these inferior people[5]. The discrimination against troubled peoples was purely an example of Intersectionality theory. Health and illness were concerned with categories of identity such as race, class, and ethnicity.

Theory

Before implementation of this law, many steps were taken. To begin, the social movement of eugenics through sterilization became apparent to eugenicists when the increase of degenerate type people was threatening American civilization. The most efficient solution was to end reproduction of these lesser people by compulsory mass sterilization[6]. With a varying array of backgrounds, there was uncertainty among the majority of American peoples, specifically the highly educated, that these degenerate peoples would have correct morals that would contribute to America as a country[7]. The biological background of peoples eventually became a worry to social elites who had influence in political power[8].

Indiana’s political parties and elites were supportive of the ideas presented in the theory of Social Darwinism[9]. This theory is similar to Charles Darwin’s (1809-1882) laws of natural selection of plants and animals but more aggressive as the weak were eradicated and the strong grew in power[10].In Indiana, human nature was of utmost interest, so in order for humans to prevail, society must be extremely strong. In order for society to be strong, there was no room for weak members[11]. This way of though of known as “Survival of the Fittest”, coined by Herbert Spencer who was alive during the process of Indiana’s sterilization law[12].

Through the theory of Social Darwinism and “Survival of the Fittest” the politicians and elites derived another theory: Degeneracy theory. This theory consisted of the belief that lower social and racial classes were predisposed to inferior status and disease causing the degradation of society[13]. Degeneracy was deemed a disease, and a vasectomy or hysterectomy represented an efficient way to prevent its transmission.

Key Actors

Highly influential people in Indiana, such as David Starr Jordan, Oscar McCulloch and Harry Clay Sharp, supported the compulsory Eugenic Sterilization Law. In fact, David Starr Jordan, was one of the leading men to work towards eradication of inferior peoples through sterilization. Jordan was the President of Indiana University of Bloomington, making him a highly intellectual man, which led him to be able to influence people, especially in the field of genetics[14]. His influence became widely known and recognized as he chaired the first ever committee regarding eugenics for the American Breeders Association in 1909[15].

Like Jordan, Oscar McCulloch held a high-ranking position, but instead of president of an education institution, McCulloch was church minister in Indiana[16]. After his own experiences, McCulloch viewed the inferior race as “parasitic” as they were vastly different to the norms of society[17]. Jordan and McCulloch had the same views of inferior groups, and banded together, after previously meeting at McCulloch’s church. McCulloch did not experience life after the Eugenic Sterilization Law was implemented as he died in 1891, however he was a key member in producing the final law[18]. With support from Jordan and McCulloch and the movement on “degenerates”, Harry Clay sharp put the law into practice, as he was a trained physician[19]

Sharp performed copious amounts of vasectomies and hysterectomies, as this was the trained way to practice the eugenic sterilization law[20]. Before the 1907 law was implemented, Sharp had been greatly persuasive to Indiana legislature. After years of convincing to prevent the reproduction of degenerates, Sharp’s pleas caught the ear of Indiana Governor James Frank Hanly, who signed the compulsory Eugenic Sterilization Law mandating sterilization for degenerates[21]. Sharp was one of the most famous physicians and continued to practice sterilization until his death in 1940[22].

Nazi Similarity

Indiana’s Eugenic Sterilization Law can be closely compared to the eugenics practiced in Nazi Germany during the Holocaust. Nazi Germany also conducted compulsory sterilization to eradicate the Jewish and inferior people in order to make the perfect race[23]. The theory of Social Darwinism is also used when describing Nazi eugenics, sterilization and racial policies[24].

Conclusion

By the early 1960s, more than 63,000 Americans were forcibly sterilized under the authority of Indiana’s Eugenic Sterilization Law[25]. On the thirteenth of February 1974, Indiana declared the official end to state-sponsored eugenic sterilization in Indiana[26]. Indiana’s past has not been openly revealed but is known, however, today eugenics and sterilization are controversial subjects that have been debated. Is it a breach of human rights or a benefit for the greater good?

References

- ↑ Lombardo, Paul A. A Century of Eugenics in America: From the Indiana Experiment to the Human Genome Era. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2010., 27

- ↑ Ibid., 28

- ↑ Levy, Leonard W., Kenneth L. Karst, and Adam Winkler. Encyclopedia of the American Constitution. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 2000., 2

- ↑ Hassenstab, Christine M. Body Law and the Body of Law: A Comparative Study of Social Norm Inclusion in Norwegian and American Laws. De Gruyter Open, 2015., 35; Lombardo, Paul A. A Century of Eugenics in America: From the Indiana Experiment to the Human Genome Era. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2010., 11

- ↑ Levy, Leonard W., Kenneth L. Karst, and Adam Winkler. Encyclopedia of the American Constitution. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 2000., 2

- ↑ Lombardo, Paul A. A Century of Eugenics in America: From the Indiana Experiment to the Human Genome Era. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2010., 28

- ↑ Hassenstab, Christine M. Body Law and the Body of Law: A Comparative Study of Social Norm Inclusion in Norwegian and American Laws. De Gruyter Open, 2015., 37

- ↑ Lombardo, Paul A. A Century of Eugenics in America: From the Indiana Experiment to the Human Genome Era. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2010., 12

- ↑ Hassenstab, Christine M. Body Law and the Body of Law: A Comparative Study of Social Norm Inclusion in Norwegian and American Laws. De Gruyter Open, 2015., 35

- ↑ Birx, H. James. Encyclopedia of Anthropology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006., 2

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Hassenstab, Christine M. Body Law and the Body of Law: A Comparative Study of Social Norm Inclusion in Norwegian and American Laws. De Gruyter Open, 2015., 34-35; Birx, H. James. Encyclopedia of Anthropology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006., 2-3

- ↑ Lombardo, Paul A. A Century of Eugenics in America: From the Indiana Experiment to the Human Genome Era. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2010., 13

- ↑ Ibid., 11

- ↑ Ibid., 17

- ↑ Ibid., 16

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., 11

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., 20

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Largent, Mark A. Breeding Contempt: The History of Coerced Sterilization in the United States. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2011., 139

- ↑ Birx, H. James. Encyclopedia of Anthropology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006., 2

- ↑ Largent, Mark A. Breeding Contempt: The History of Coerced Sterilization in the United States. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2011., 1

- ↑ Lombardo, Paul A. A Century of Eugenics in America: From the Indiana Experiment to the Human Genome Era. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2010., 37

Submitted by: Isabelle C.R. Durrans