Course:GEOG350/Archive/2013ST1/Old Japan Town

Introduction

Japantown, Vancouver, Also referred to as Little Yokohama or Little Tokyo, was an area located north of China Town.

Japanese workers flocking to Vancouver in the late 1800's looking for work in the fishing and lumbering industries settled in the area. The community continued to grow as more and more immigrants from Japan continued to flow into the country and settle in this area. During World War II, Japanese residents were forcefully removed from their homes, and their possessions and property confiscated and sold. After the war ended, some of the area's former Japanese residents went back to the area even though they had no homes to return to, but the community never revived. Japantown ceased to be an ethically Japanese settlement, and the historic Japantown area is now interchangeably called the Oppenheimer District: an area within the larger Downtown Eastside (DTES).

The forced removal of an entire ethnic community is a sad chapter of Canada's history. The remnants of Japantown are historically significant, and an effort should be made to preserve what is left of its architecture and history. Acknowledging the history attached to the area will act as an opportunity to teach about the tragedies of war, Canadian history, immigration, multiculturalism and the industrial revolution. Additionally, it will honour the memory of the Japanese-Canadians interned during WWII. These issues will be considered in the context of the site's history, the present day demographic, and issues affecting the larger context of the DTES such as social housing and gentrification.

History

“The physical neighbourhood pre-dates Japanese Immigration, it's streets laid out at the time of the city's incorporation in 1886. [1]” The area played a large part in the founding of Vancouver because of it's proximity to the central concentration of business to the west of Gastown, and as a settlement for workers that supported the industry happening in the area. It was also home to many Aboriginal workers, many of whom lived and worked in the area. [2]

The area began to see an influx of Japanese immigrants in the late 1800’s and as wealthier residents left for the west end, Vancouver’s first cultural institutions and churches were established in the area. By the early 1900s, Powell street (300-400 blocks) and parts of Alexander Street made up the centre of Vancouver’s Japantown. Originally, only men were allowed by the Canadian government to immigrate, and they settled in boarding houses near the Hastings Sawmill where many of them worked. A growing population of immigrants setup shops, markets, and their homes in this community that was a part of a very young Vancouver at the time. The Vancouver Japanese Language School, Japanese Hall and Japanese Methodist Church were established in the thriving neighbourhood.[3] The Vancouver Japanese Language School and Japanese Hall established in 1906 remains even today, they are located at 475 and 487 Alexander Street respectively. The Methodist Church, now the Vancouver Buddhist Church at Powell and Jackson, was essentially the “Community Centre” for the Japanese-Canadian community that spread for many blocks from the epicentre of Oppenheimer Park, located between the four streets of Cordova, Powell, Jackson, and Dunleavy Streets.[4] The Japantown area, centered around Oppenheimer Park, was attacked by the Asiatic Exclusion League on September 7th 1907, a group opposing the mass immigration of people from Asian countries. [5] This attack began in Chinatown, and then proceeded to Japantown, causing considerable damage to the area, despite the resistance efforts of residents. The Powell Street Grounds, now Oppenheimer Park, was the location of a riot related to Bloody Sunday, a workers demonstration in 1938.

The Japantown neighborhood was a vibrant commercial and residential district which constantly mixed traditional Japanese culture with contemporary Canadian convenience. John Endo Greenaway lists 10 points that made this area unique:[6]

- Powell Street was a family neighbourhood. Many families lived in small apartments above or behind their storefronts. Larger homes lined East Cordova and Alexander Streets. Narrow alleys, or breezeways, connected the front of the street to the back alley.

- With both parents working, children had a huge amount of independence. They played freely in the lanes and empty lots. They attended both English and Japanese school. Many children took music, odori or judo classes as well.

- Powell Street was a treasure trove of special Japanese foods and ingredients. At least twelve Japanese restaurants served the area, confectionary stores sold freshly-made manju, and several tofu-ya were active.

- Powell Street was a thriving commercial district offering specialty Japanese goods and services. By 1921, the area bustled with over 578 ethnic Japanese stores and businesses.

- Japanese style ofuro (bathhouses) were found on almost every block. Many people did not have private baths in their homes.

- Both Christian churches and a Japanese Buddhist Temple were active in the Powell Street area. All the faith organizations on Powell Street were important social gathering places.

- Powell Street was alive with sound! From contemporary pop to traditional Japanese songs, music of all styles and genres could be heard on Powell Street.

- During special occasions, young odori dancers would dress in their finest kimono and proudly represent the Japanese Canadian community in elaborate parades.

- People on Powell Street loved baseball! Huge crowds loved to watch the Asahi baseball team at Powell Grounds, later renamed Oppenheimer Park.

- Sports and social clubs were popular among all age groups on Powell Street. Shibai (plays) or concerts were held at the Language School hall. The kenjinkai (prefectural association) hosted annual picnics.

The Japanese community's vibrant and bustling economic centre of the 1920s-1930s was socially destroyed during World War Two. During the Second World War, due to pressure from the citizens of British Columbia, the federal government forcibly removed Japanese Canadians from the area. During this period, Japantown became a dead zone [2]. The forced departure of the Japanese-Canadians and the sale or dispersal of all their property caused the local economy to take a downturn. The area has suffered through fluctuating economic and social conditions since then.[7] Even though the War Measures Act lifted in 1945, only a small portion of the former residents relocated to the former Japantown area. This was in part due to the conservative MP in BC, Howard Green, campaigning for the deportation of people of Japanese decent from BC. Japanese Canadians were not allowed to return to the coast until 1949.[8] In 1941, BC was home to 95.5% of the Japanese-Canadian population in Canada, but by 1947 the Japanese Canadian population in BC had dropped to 33%. [9] The city then attempted to rezone the area as a entertainment district in the 1950’s, however the decline in the local industries led to a local rise in unemployment.

During the mid 1950s to the mid 1970s the area was relatively quiet, and the cities redevelopment plans and blight clearance initiatives threatened to destroy its remaining history, making way for high-rise towers and freeways. In the mid 1970’s however, amongst the redevelopment, a cultural renaissance occurred, which saw the government focus on redeveloping the infrastructure and facilities in the area, including the Japanese Language School. The annual Powell Street Festival, a celebration of Japanese heritage, began in 1977 and continues today. This led to the symbolic start of Japanese cultural recovery in the area, which aimed to attract the descendants of immigrants back to inhabit the area. [2]

Unfortunately the renaissance was short lived. With the gentrification of Gastown, low-income residents were forced east. With the introduction of one way streets through the area, the former Japantown (now a part of the Oppenheimer District) became more of a drive through neighbourhood leading commuters downtown. With all of this occuring in the 1980’s, the area again experienced a cultural renaissance in the 1990’s, stemming from the work and passion of local residents and cultural associations.

The majority of the economic and cultural activity related to the Japanese community has moved in recent years to a small area called Little Ginza, now located around Alberni Street and Burrard and the West End's Robson and Denmann Streets. The Little Ginza area has several high end restaurants, shops, clubs and karaoke bars all targeted at Japanese tourists. This area has little true cultural significance as nothing more than a space for consumption rather than community.

Present Day Oppenheimer District

The former Japantown, concentrated between Gore St and Jackson Street, from the waterfront south to Cordova street, is now considered a part of the Downtown Eastside. The issues of drugs, crime, gentrification, affordable housing, and post-industrial neighbourhood decline associated with the Downtown Eastside define the current context of former Japantown. The users of Oppenheimer Park are overwhelmingly marginalized [10] . On top of these concerns is the issue of whether, and in what form, the preservation of the neighbourhood’s historical and cultural significance will take. [11]This question of how this lost historic neighbourhood should be remembered is worth analyzing because its history is threatened by the rapid changes and development happening within the Downtown Eastside and its surrounding neighbourhoods. Recently, gentrification and the possible ousting of Downtown Eastside residents has met with protests and arson [12]. [13] Resistance towards gentrification in the DTES has resulted in 'unexpectedly low indicators of gentrification' due in great part to policy that focuses on social housing provision[14]. Although filled with low-income residents, it is a relatively stable community which, year after year, has had to combat redevelopment in the area. For better or worse, change on the DTES is happening, and the frontiers of gentrification will likely close in on Japantown in a matter of time [15]. As such, policy and other initiatives will play an important role in the development of this historical area.

During most of the year, Oppenheimer Park and the surrounding area is characterized by the agglomeration of drug users in it’s streets [16]. Oppenheimer Park is also the site of the annual Powell Street Festival. The two day festival which began in 1977 is held on the first weekend of every August, and is a community celebration of Japanese heritage as well as the alternative street culture of the Downtown Eastside (DTES.)[17]

Transportation

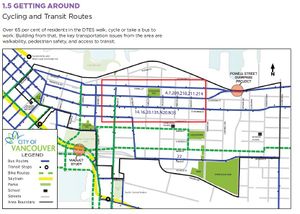

During the early 20th century, Japantown and the DTES became a major retail area, and as a result was a large hub for transportation which included the BC electric interurban substation (terminus for they city's streetcar program), North Shore Ferries terminal, and the coastal steamship piers. At the time, this brought a large amount of the population into the area simply as a terminal to get to other areas of the downtown core. The discontinuation of the streetcar program in 1958, along with the shutdown of the North Shore ferries service the following year greatly reduced the number of individuals who flowed through Japantown and the DTES on a daily basis, as these individuals were now routed through other areas of the city. [18]

Currently, transportation in the area is defined by one way streets, designed to allow people to drive through the commuter neighbourhood, severing the community's connectivity to the rest of the city. Public transportation in the form of street car’s once existed in the area before 1955 [19], however streetcars have since been replaced by buses that run through the area instead.

The DTES is currently undergoing major transportation changes. The Georgia and Dunsmuir Viaducts are "two elevated roadways connecting the Eastern Core area to downtown Vancouver – are remnants of a 1960s freeway system that was abandoned after public opposition [20]. The viaducts have been criticized because they prioritize car traffic, causing a barrier between downtown and East Vancouver for pedestrians, disconnection between neighbourhoods, and speeding in the residential zones connecting to the viaducts. The city is in the process of reviewing proposals to remove the viaducts. Currently in construction, the "Powell Street Overpass project is a $50-million major road and rail infrastructure enhancement for a section of Powell Street in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, just west of Clark Drive. [21]" This project will service the port of Vancouver by increasing the capacity to move goods, while aiming to improve conditions for cyclists and pedestrians commuting on the Powell Street traffic corridor.

A 2006 census shows that 65% of the DTES community commute to work by walking, cycling, or public transit, while 33% commute by car, motorcycle, or taxi. In Vancouver, this same statistic is 41% and 59% respectively. "Access has been difficult for low-income peoples in the DTES who can't afford transit or cars."[22] Currently, there is a large focus on pedestrian improvements in the areas surrounding Oppeheimer Park. The improvements are specifically aimed at increasing the safety and comfort of pedestrians along this area. This is proposed to be done by 2040, and will include more waiting areas, better sidewalks, increased lighting and seating, and better landscaping of the area. In effect this will result in an even greater percentage of the DTES population using sustainable means of transportation, increasing the walkability score and helping local residents reduce their cost of living. [23]

Demographics

One of the oldest neighborhoods in Vancouver, Japantown was home to over 8000 Japanese Canadians until their forced removal in 1942. Despite a majority of its residents being Japanese, the Powell Street Area was a multicultural neighborhood which housed many other nationalities as well. The waterfront community offered accommodations to First Nations and other immigrants who had no other place to stay.[24] After 1942, few Japanese-Canadians returned to the neighborhood. Only after heavy lobbying did culturally important building such as Japanese Vancouver Japanese Language School and the Japanese Hall on Alexander Street return to the community in 1952. Despite the role of Japanese in the areas founding history, "if you visit the area today, there are almost no signs of the large Japanese Canadian community and the activity that once filled the streets."[24]

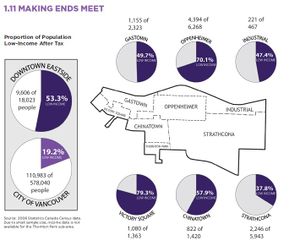

Currently, Oppenheimer is a main residential neighbourhood within the Downtown Eastside. The Oppenheimer area holds a population of 6,108 people or 33% of the Downtown Eastside population of over just 18,000 residents, despite being much smaller in total area than Strathcona. The area has experienced 5% growth in population between 2001-2011, which is the lowest percentage of population growth out of all Downtown Eastside areas, except for Strathcona.[25]

The Gender profile in the Oppenheimer area is split roughly 65% male residents and 35% female residents, which is close to the average for the Downtown Eastside which falls at 60% male and 40% females. Census data shows that the DTES area on average contains a higher percentage of peoples aged 45 and above compared to the rest of the Vancouver area. The average age profile of the Downtown Eastside area ranked as follows:[26]

| Age Profile | DTES | DTES | DTES | Vancouver | Vancouver | Vancouver |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 2001 | 2006 | 1996 | 2001 | 2006 | |

| Under 5 Years | 3% | 2% | 2% | 5% | 4% | 4% |

| 5 - 19 Years | 9% | 8% | 8% | 15% | 14% | 14% |

| 20 - 44 Years | 40% | 39% | 37% | 47% | 45% | 45% |

| 45 - 65 Years | 27% | 28% | 31% | 21% | 23% | 26% |

| 65+ Years | 21% | 22% | 21% | 12% | 13% | 13% |

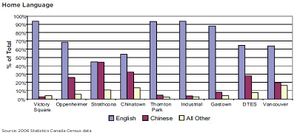

Statistics Canada Census data shows that while areas such as Chinatown and Strathcona are 45% non-immigrants with 55% immigrants, the Oppenheimer area currently consists of 60% non-immigrants and 36% immigrants. Within this, 70% of these households speak English as their main language, while 25% speak Chinese, and 5% speak other languages.[27]

The Downtown Eastside is currently comprised of 1,705 Aboriginal peoples, which accounts for 10% of the Downtown Eastside population, as well as 15,295 non-Aboriginal peoples.[28]

| Ethnic Background | Vancouver | DTES |

|---|---|---|

| Aboriginal | 11,140 | 1,705 |

| Non-Aboriginal | 560,455 | 15,295 |

"Although Vancouver is a city known across the world for its high standard of living, many groups across the city live in poverty, struggle with mental health issues and addictions, or are unemployed.Although Vancouver is a city known across the world for its high standard of living, many groups across the city live in poverty, struggle with mental health issues and addictions, or are unemployed[29]" Data from Statistics Canada shows that 44.6% of children under 6 are living in low income families in the DTES and Oppenheimer area. This number is 2.5 times greater than that of the rest of the City of Vancouver.[30] A study conducted by the City of Vancouver shows that there are 14 Childcare and School Facilities for the residents of the DTES: 11 of these 14 facilities are located in or in close proximity of the Oppenheimer area.[31]

Census data reveals that apartments make up almost 90% of housing in the DTES. 88% of the DTES consists of renters, compared to the 12% that actually owned homes in this area. These figures compare to Vancouver, which has a renter and owner ration of almost 1:1. Although this data is the average for the DTES as a whole, the residents of the Oppenheimer area most likely do not deviate too far from this trend.[32] Rent prices in Oppenheimer are slightly less than the rest of the city. Census data shows that more than 51% of DTES renters paid 30% or more of their household income on shelter costs compared to the 23% paid in Vancouver.[33]

The unemployment rate in the DTES in 2005 was 11.3%. 4340 men and 2640 women from the DTES area were working. This area has the lowest per capita income of any urban area in Canada, with 63.3% of the population considered as low income residents. The average earnings for these residences were $12,928 in 2005 from the $10,383 in 2000. A large portion of this population is considered part of the working poor.[34]

The level of education in the DTES area is extremely low compared to the rest of the city where 40% hold university diplomas while only 15% have below highs school level education. In contrast to this, 45% of Oppenheimer residents above the age of 15 had below high school level education: 25% had High School educational certificates, 10% had apprenticeship or trade certificates, 10% had college degrees and 10% had university diplomas.[35]

A high percentage of residences of the DTES are not living in families. Over 70% of Oppenheimer residents are single person occupants, while only 30% are multiple person families (usually 2-3).[36]

Life expectancy in the DTES is 4.6 years lower than the city average, with a large portion of this discrepancy coming from the male population. Crime is rampant and access to medical care services are disproportionately lower in the DTES than the rest of the city. DTES residents visited emergency rooms more than 10,000 more than Vancouver residents, yet there are only 15 medical specialist per 100,000 in the DTES compared to 232 specialists per 100,000 in Vancouver.[37]

| Crime Type | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Homicides | 5% |

| Serious Assaults | 30% |

| Sexual Abuse | 15% |

| Robberies | 20% |

| Break & Enters | 10% |

| Thefts | 10% |

| Public Intoxication | 15% |

Issues

One of the main issues involving former Japantown is how to remember and preserve the important history of the area, while continuing to serve the needs of the area's current residents [38] [39]. In spite of various initiatives by the city and Japanese community partners [40]to revitalize the area while in tandem acknowledging it's rich history, the solutions have been well-intentioned but superficial for the most part. Once a year, the successful Powell Street Festival gathers people at Oppenheimer Park in a celebration of Japanese-Canadian history and culture, drawing people to the area and creating a sense of community. During the rest of the year, the former Japantown is only recognized by innocuous signage scattered throughout the area. These efforts are a positive gesture, however there is potential to make deeper, more meaningful connections between the urban form and the history of the neighbourhood. By taking measures to preserve and promote the history of Japantown, we can remember this tragic piece of Canadian history as a means to promote peace and multiculturalism, bring communities together, and encourage tourism. Selling ethnic neighbourhoods as places of leisure and consumption is a rising trend, and the commodification of ethno-cultural diversity “creates new opportunities in otherwise blighted neighbourhoods.” [41]. Examples of this include Seattle's International District, which includes a significant Japanese history, and San Francisco's Japantown are established tourist destinations. The Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience can be found within Seattle's International District. The museum is housed in a historic former hotel, an act of preservation that will help future generations understand the experience of Asian immigrants. Wing Luke Museum exhibitions tend to focus on cultural understanding, Asian American history, and human rights. In Vancouver's former Japantown, opportunities to recognize and preserve the area’s historic significance should be examined by city planning to protect the few remaining historically significant remnants of the neighbourhood from being completely lost.

BT Vancouver: Historic Building Demolished

Analysis of Causes

The loss of Vancouver's Japantown is a direct result of the internment of Japanese-Canadian immigrants during WWII and the seizure and selling off of their property by Canadian authorities. The abrupt injustice forced upon the Japanese-Canadian community practically erased the neighbourhood as it existed. None of the property in the former Japantown was retuned to the Japanese community after the war, with the exception of the what is now the Vancouver Japanese Language School & Japanese Hall [42].

One main factor that effects the issues of historical preservation is the Downtown-Eastside/Oppenheimer District (DEOD) zoning designation. Vancouver's current zoning map states that “the intent of this District and accompanying official development plan is to retain existing and provide new affordable housing for the population of the Downtown-Eastside Oppenheimer area, and to provide for compatible commercial and industrial uses in some areas.”[43] The industrial roots of the area were the reason Japanese migrant workers settled here in the late 1800's, near industry occurring on and around the waterfront. Sometime after WWII, much of Vancouver's early industry moved to the periphery of the city, and the many of the DTES's industrial buildings fell into disuse. The DEOD zoning plan envisions this declining industrial zone as an opportunity to addresses social needs by prioritizing social housing and concentrating it in one part of the city. These plans fail to promote the preservation and promotion of the historical significance of the area. Social housing development trump historic building designation under the DEOD zoning bylaws, which could lead to the loss of buildings, some already on Vancouver's heritage register, significant to the Japanese-Canadian community.

The population of the Downtown Eastside is reputed to be the 'poorest postal code in Canada' [44] and this vulnerable population faces issues such as homelessness, crime, and addiction. Former Japantown is considered part of the Downtown Eastside, and these same issues must be addressed when talking about the revitalization of Japantown. Businesses that could play a role in the revitalization of the area may be discouraged from moving in given the area's demographics and the traffic routing that treats the area as a place to pass though. On the other hand, there has been resistance to gentrification of the Downtown Eastside that has been seen recently in the form of protests in the Gastown area.

Japantown Revitalization

Some may view the beautification of Japantown as an act of (or gateway to) gentrification, which would lead to the displacement of the neighbourhood's vulnerable population. Others may view assigning historical value to the areas buildings as a way to help resisting change, involving more communities in protecting the area. In 2008, the Japanese community successfully petitioned the Park Board's redesign of Oppenheimer Park, which would have seen the removal of commemorative cherry trees planted by the community in 1977 [45]. Current research on the revitalization of Japantown recognizes the complexity of revitalizing Japantown, drawing connections between the history of human rights violations to the present day context in the DTES[46]. In July 2013, the uninhabited Yamagashi building on Powell Street's 400 block was near collapse and demolished for safety reasons [47]. The state of many of these buildings indicates an urgency to address the issue of historic preservation. This can be accomplished at an individual scale through programs such as the US Federal Historic Preservation Tax Incentives could be a good model for promoting the investment of sweat equity into properties of historic significance. The issues are enveloped in the larger context of the DTES, which includes concerns of the dislocation of vulnerable groups associated with community revitalization and gentrification. Currently, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) funded “Revitalizing Japantown?” research project “engages Downtown Eastside (DTES) residents, organizations and artists who are working with a team of researchers with grassroots experience in the community. The goal of the project is to recover the long Human Rights history of the neighbourhood while doing our part to ensure that the rights of current DTES residents remain a public priority. To accomplish this we’re working with the 5 founding communities of the DTES: Coast Salish people, the Low-Income community, Chinese Canadians, Japanese Canadians and African Canadians[48].”

References

- ↑ Kobayashi, Audrey. Memories of Our Past: a Brief History and Walking Tour of Powell Street. Vancouver: NRC Publishing, 1992.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Birmingham and & Wood Architects and Planners. 2001. Historical and Cultural Review of Powel Street (Japantown)

- ↑ Bollwit, Rebecca. ""Vancouver History: Japantown." May 30, 2011. Accessed August 7, 2013. http://www.miss604.com/2011/05/vancouver-history-japantown.html.

- ↑ Anderson, Patrick. [http://www.vancouverweekly.com/my-vancouver/ "My Vancouver: Old Japantown" Accessed August7, 2013.

- ↑ "Commemorating a race riot", 2007

- ↑ Greenaway, John Endo. "Monogatari: Tales of Powell Street 1920-1941." The Bulletin. N.p., n.d. Web.

- ↑ Greenaway, John Endo. N.p., n.d.

- ↑ Hickman, Pamela and Masako Fukawa. Righting Canada's Wrongs: Japanese Canadian Internment in the Second World War Toronto:Lorimer, 2012

- ↑ Hickman, Pamela and Masako Fukawa. 2012.

- ↑ "Ellison, Simon. 2007. Oppenheimer park: A study of interconnectivity in the public realm. Ph.D. diss., Dalhousie University (Canada)

- ↑ Tiffin, Benjamin Tsuyoshi. "Revitalizing Vancouver’s Japantown: An Architectural Response to Japanese Food." Master’s thesis, Dalhousie University, 2012

- ↑ Mickleburgh, Rod. "Gentrification opponents take aim at Downtown Eastside condo project." The Globe and Mail March 25, 2013. Accessed July 15, 2013. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/british-columbia/gentrification-opponents-take-aim-at-downtown-eastside-condo-project/article10336053/

- ↑ Lee, Jeff and Zoe McKnight. "Anarchists claim responsibility for torching East Vancouver duplex." The Vancouver Sun. Sun May 17, 2013. Accessed July 15, 2013. http://www.vancouversun.com/news/Anarchists+claim+responsibility+torching+East+Vancouver+duplex/8394364/story.html

- ↑ Ley, David and Cory Dobson. "Are There Limits to Gentrification?: The Contexts of Impeded Gentrification in Vancouver." Urban studies. 45 (2008): 2471 - 2498. Accessed July 15, 2013. doi: 10.1177/0042098008097103

- ↑ Samuel, Sigal. 2013. "Bad neighbours: new condos are the start of gentrification in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside." This Magazine, March 3, 2012.

- ↑ "Homeless gather in Oppenheimer Park" The Vancouver Sun. August 9, 2008. Accessed: August 7, 2013. http://www.canada.com/vancouversun/news/westcoastnews/story.html?id=e4dcd78e-2293-47ac-8e0c-8079bdd8f0c1

- ↑ Powell Street Festival, Official Website.

- ↑ Strathcona Business Improvement Associatio. "Vancouver's Downtown Eastside: A Community in Need of Balance. 2011. http://strathconabia.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/DTES-A-Community-in-Need-of-Balance.pdf

- ↑ Vancouver Heritage Foundation. "Vancouver Transit: The Era of Street Cars" Spacing Vancouver. June 18, 2013. Accessed: August 1, 2013. http://spacing.ca/vancouver/2013/06/18/vancouver-transit-the-era-of-street-cars/

- ↑ City of Vancouver. "Georgia and Dunsmuir viaducts study" Last modified: June 20, 2013. Accessed: July 15, 2013. http://vancouver.ca/home-property-development/viaducts-study.aspx

- ↑ The City of Vancouver. "Powell Street Overpass project" Last modified June 5, 2013. Last accessed: July 15, 2013. http://vancouver.ca/home-property-development/powell-street-overpass-project.aspx

- ↑ City of Vancouver. "Downtown Eastside (DTES) Local Area Profile 2012. City of Vancouver. 2012. pg 19.

- ↑ The City of Vancouver. "Downtown Eastside Local Area Planning Program" July 2013. http://vancouver.ca/files/cov/downtown-eastside-local-area-plan-open-house-boards-07182013.pdf

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Greenaway, John Endo. N.p., n.d.

- ↑ City of Vancouver. 2012. 6.

- ↑ City of Vancouver. 2012. 7.

- ↑ City of Vancouver. 2012. 8.

- ↑ City of Vancouver. 2012. 9.

- ↑ "Downtown Eastside Local Area Profile 2012. Accessed August 1, 2013. http://vancouver.ca/files/cov/profile-dtes-local-area-2012.pdf

- ↑ City of Vancouver. 2012. 10.

- ↑ City of Vancouver. 2012. 11.

- ↑ City of Vancouver. 2012. 12.

- ↑ City of Vancouver. 2012. 14.

- ↑ City of Vancouver. 2012. 22.

- ↑ City of Vancouver. 2012. 23.

- ↑ City of Vancouver. 2012. 29.

- ↑ City of Vancouver. 2012. 27.

- ↑ SUNN Vancouver Historic Quartiers. "Revitalization in Japantown." Accessed July 19, 2013. http://sunnvancouver.wordpress.com/2011/06/19/revitalization-in-japantown

- ↑ City of Vancouver. Great Beginnings:Old Streets,NewPride: June 2009 Project Progress Report, Vancouver, BC, 2009. [1]

- ↑ Takeuchi, Kenneth. Letter to Mayor Michael Harcourt, 20 Jan, 1982. Japantown Beautification File: 5463-9, Vancouver City Archives, Vancouver.

- ↑ (Aytar, Volkan and Jan Rath. Selling Ethnic Neighbourhoods: The Rise of Neighbourhoods as Places of Leisure and ConsumptionNew York: Routledge (2012)

- ↑ Atkin, John. Vancouver Heritage Foundation walking tour by John Atkin. Vancouver, BC, July 15, 2013.

- ↑ City of Vancouver. City of Vancouver Zoning Map. Last modified September 21, 2010. http://vancouver.ca/files/cov/Zoning-Map-Vancouver.pdf

- ↑ Matas, Rober and Ingrid Peritz. "Canada's poorest postal code in for an Olympic clean-up?" The Globe and Mail , Aug. 15 2008. Accessed July 01, 2013. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/canadas-poorest-postal-code-in-for-an-olympic-clean-up/article1059406/. [2]

- ↑ "Save the Legacy Sakura of Oppenheimer Park! "Accessed: August 5, 2013. http://www.greenclub.bc.ca/Cherry_Fest/Memory/memory.htm

- ↑ Masuda, Jeff. "Announcing a New Research Partnership on Human Rights and Place in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside." Accessed August 5th, 2013. http://www.cehe.ca/urbanhealth

- ↑ "BT Vancouver: Historic Building Demolished" Accessed: August 5, 2013. http://video.citytv.com/video/detail/2565951196001.000000/bt-vancouver-historic-building-demolished/

- ↑ "REVITALIZING JAPANTOWN? A Unifying Exploration of Human Rights, Branding, and Place" Accessed August 7, 2013. http://www.revitalizingjapantown.ca/