Course:GEOG350/Archive/2013ST1/Gentrification Downtown Eastside

Group Members

Daren Johannesen, Alex MacLeod, Michelle Ho Suet Yeung

Neighbourhood Analysis: Vancouver's Chinatown

Location

Chinatown is primarily located on Pender Street, which is referred to as the 'main artery' of Chinatown, other streets include Main Street, Keefer Street, and up to Hastings Street (X). The center is located around the (CCC) or the Chinese Cultural Center which is on Pender Street. To get to Chinatown from the Downtown core you must pass through the millennium gate. This archway is a symbol of both the past and the future, combining traditional and modern Chinese architecture to further bring together the neighborhoods that are located around Chinatown. The whole area was declared a historic site in 1971, along with the surrounding neighborhood Gastown (X).

Figure-1. The Areas of DTES (in blue) and Chinatown (in red) in Vancouver.

Figure-2. The Millennium Gate on Pender Street in Vancouver Chinatown.

Historical Evolution

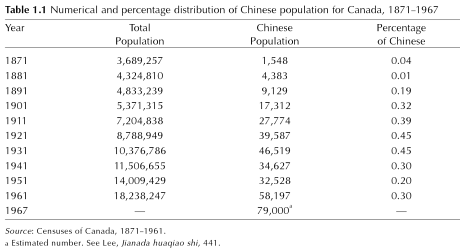

Vancouver has a large history of Chinese immigration, dating back to the late 1800's when Chinese immigrants came over to Vancouver to work on the roads and railroads. Immigration of Chinese immigrants was restricted and regulated in 1885, when there was a $50 head tax put onto Chinese labor workers. Between 1890 and 1920, early Chinese immigrants settled in a two locations that were named Shanghai Alley and Canton Alley. In 1898, a Chinese theatre that could hold 500 people was built, and this was the center of all entertainment and the locations where most of the community’s activities took place. In 1923, a new immigration act – “Chinese Exclusion Act” was implemented, which disallowed Chinese immigrants. Hence, there was a sign of decline in Chinese immigrants coming to Vancouver during the period of 1930s to 1940s. It was not for another 44 years before Chinese immigrants were allowed to immigrate into Canada on the same basis as other immigrants (X). As a result, the population of Chinese immigrant had risen from 39,587 in 1921 to 79,000 in 1967, a 50% increase. (Censuses of Canada, 1871-1961)

Figure-3. Numerical and percentage distribution of Chinese population for Canada, 1871 – 1967 [Source: Censuses of Canada, 1871 – 1961]

The 1986 World Expo attracted a large number of Chinese immigrants into Vancouver, of which the majority being from Hong Kong. This led to the nickname 'Hongkouver'. With reference to the 2002’s Citizenship and Immigration Canada Statistics, there is an average of 30,000 Chinese Immigrants into Canada each year since 2000, with no sign of slowing down to more than 40,000 in 2005. One of the buildings in Chinatown, called the Sam Kee Building, is very unique and it is considered to be Chinatown’s most famous landmark. The 1913 built building is steel-framed and is only 4 feet 11 inches wide on the ground. According to the Guinness Book of World Records, this is the narrowest commercial building in the world. This was all because of the widening of Pender Street in 1921 as well as the importance and knowledge of property owner Sam Kee and the architects Brown and Gillam (X).

Today, Chinatown has an authentic oriental atmosphere, and many of the buildings in that area have an authentic oriental style structure that has been well-preserved. Vancouver's Chinatown is near the top of the list of the cleanest modern day Chinatown's in North America (X). It calls home to a number of specially designed heritage buildings that bring about a rich history of early Chinese pioneers.

It is also interesting to point out how Chinatown’s exact contours formed. Edgar Wickberg, a UBC Chinese History professor, indicates that “as the population grew, the different associations and shops needed more space, particularly in the 1020s.” Consequently, the area has shifted east to Carroll Street and Main Street and into today’s Chinatown.

Demographic Characteristics

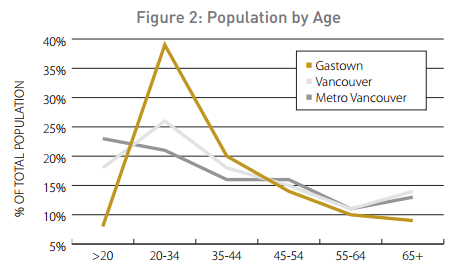

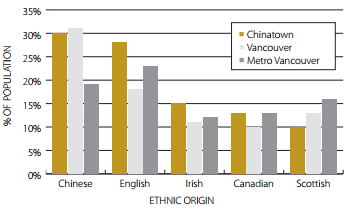

Chinatown is considered to be fairly concentrated with a population density of 5,810 per sq. km, only 5,039 for Vancouver and 736 for Metro Vancouver. This area has approximately a total of 26,600 residents, more men (57%) than women (43%), along with a much faster population growth rate than the Metro Vancouver city. The median age is between 25 and 44, with more elders than children. Also, a very large portion of Chinatown's demography lies in the immigrant population. Being one of the several neighborhoods of the Downtown Eastside, it has a common demography to those neighborhoods, the only large difference being that Chinatown has a larger Asian population than the surrounding areas. At least 71% of the population is Chinese, even though 66% of them listed English as their mother tongue.

Figure-4. Population by Age

Figure-5. Percentage of Ethnic Origin

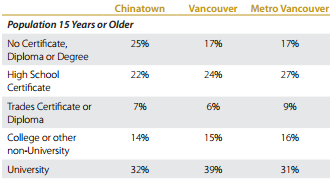

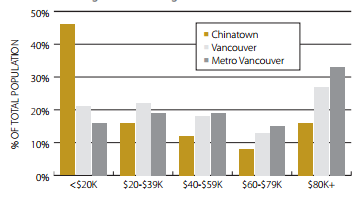

Another demographic feature of Chinese communities worth mentioning is the economic aspect of Chinatown. According to Figure 4 shown below, 25% of the residents have no qualification, as opposed to Vancouver’s and Metro Vancouver’s 17%. As a result, Chinatown has a relatively higher level of unemployment rate of 7.4% and only half of the residents are employed; as opposed to Vancouver’s 6% unemployment rate and 62% of employment rate. As witnessed, Chinatown isn’t as developed and as glamorous in comparison with the city or the region and therefore a lower level of income. Figure 5 shows that there are significantly more residents at the bottom level ($20k or below) of the income spectrum, and relatively fewer at the upper level of the spectrum ($60k or above).

Nevertheless, the average household income should not be taken into complete consideration. This is because most of the households are single-person, as opposed to big families in the city. This brings us to the next profile of Chinatown – Housing.

Figure-6. Education Attainment Level

Figure-7. Average Household Income

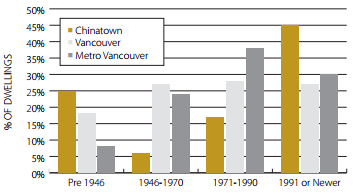

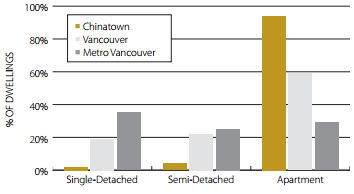

Despite being one of the places where immigrants first settled and a handful of heritage buildings, 45% of the buildings in Chinatown are built after 1991 comparing to only 27% for Vancouver. Chinatown’s dwelling structures are predominantly apartments (94%), which explains the higher than average population concentration in the region. Housing price and rents are extensively cheaper than those of its up-scale neighborhoods such as Yaletown. Nevertheless, Chinatown is a neighborhood with continuous gentrification, therefore pricing varies. Likewise, commercial lease rate is known the cheapest in the city as well. It costs approximately $15 to $30 per square foot, that is only a tenth of the average lease rate of Downtown Robson Street.

Figure-8. Age of Housing Stock

Figure-9. Dwellings by Major Structural Type

Current Urban Issues

Issue of Poverty

Many of the more western neighborhoods of Downtown Vancouver don't see as much drug use and disease infection, whereas places like Chinatown get a lot more due to how close they are to the Eastside (X). Chinatown’s Cordova and Hasting streets that were once the central shopping area of the city, but the shops that used to be flourished did not survive the area’s urban decay since 1980s. Since then, this area is infamous for its high level of poverty, homelessness, drug use, street prostitution, crime as well as violence.

Despite being a victim of significant urban decay, the community has been going through gentrification development. Many buildings are being renewed and new trendy businesses are operating in the community. Overall, this plan aims to improve the standard of living of the existing residents as well as to improve the overall atmosphere around the area.

Chinatown in Transition

For the majority of its existence, Chinatown has been home to mostly low-income individuals and families (1). But recently, perhaps due to its proximity to the downtown core, the neighborhood has seen new, wealthier residents moving in. To the west and to the south rise new high-end condominiums are being constructed and sold at a premium. Chinatown residents likely cannot afford to live in such residences and as land values rise, they cannot afford to remain in place. Land values and rents are skyrocketing as a result of a red-hot housing market (2). Residents who have called Chinatown home for as long as they can remember now have to pack up and leave because they can no longer pay the rent. Landowners are selling and developers are buying at an unprecedented rate (1).

So why is Chinatown of all places becoming the next place to be? (Underlying Causes)

There are a number of factors contributing to this somewhat sudden surge in interest. First of all, there is the convenient location. For an area that borders the downtown core of one of the most expensive cities in the world, Chinatown’s rental rates and land values are comparatively low when compared to other neighborhoods bordering downtown (X). This has meant that for first-time homebuyers, they can live near the city center and have comparatively affordable rents or purchase prices. Second is transportation. The neighborhood is anchored by a major terminus bus station and a rapid transit station (Main Street-Science World Expo Line Sky train Station) and is within walking distance to another (Stadium-Chinatown Expo Line Sky train Station). Take away the grime and crime and you get a very desirable place to call home. But by doing so, by creating a place for the wealthy, the poor and even middle-class residents are being displaced (X). And to many, that less-than-sterile atmosphere that Chinatown currently has is not necessarily a negative characteristic. Vancouver has many newer and denser neighborhoods that lack any sort of community feeling or that have a personality or sense of place.

Issue of Gentrification

Gentrification is the social, economic, and cultural transformation of a predominantly low-income neighborhood through the deliberate influx of upscale residential and commercial development. Neil Smith, an urban theorist, says that “Gentrification has become a strategy within globalization itself; the effort to create a global city is the effort to attract capital and tourists, and gentrification is a central means for doing so.” This kind of restoration and improvement of the city are rooted in the colonial doctrines of discovery as well as a form of globalization, which is fuelled by the neo-liberal urbanism process.

What is Being Done?

Currently, Chinatown’s business markets are mainly lower order and working class goods such as secondhand clothing shops and souvenir stores. As such, there is an obvious decline in foot traffic and a fall in activities. Commercial property vacancy rate in Chinatown has dropped to only ten percent, with shops going out of businesses or moved out of the neighborhood. Chinatown is crying for help and a new fresh approach to restore this area of developments.

The objective of the Redevelopment Plan is to attract people from all kinds of background to Chinatown and bring a new flow of income and vibrancy into the once ghetto streets. For instance, one of many plans was to attract younger entrepreneurs by offering them affordable rent prices, and thus bringing in a new crowd and positive flow of energy. Another strategy is to encourage new businesses to move in, opening non-tradition stores such as contemporary galleries, as a ways of restoring storefronts and to attract higher-income people feel more comfortable and secure in this area. Furthermore, the city’s councilors have raised the height of building restrictors with more condominium towers under constructions.

The new diversity of businesses and the extra supply of affordable condominium are thought to be necessary to create a new positive image for Chinatown and a way to dilute social problems, in order to transform into a more “chic” neighborhoods such as Yaletown and Gastown.

Figure-8. 11 High-level Chinatown Vision Directions

Who is it Affected?

Many protesters pointed out the “violence of gentrification”, which is a three-fold ideological explanation aimed at giving it an air of reasonableness.

- Urban renewal. This believes that the downtrodden ghetto will be improved and revitalized through commercial activities and social investment, which is now a widely questioned theory at the global level. There are current residents that fear as trendy businesses move in, it will overwhelm and push out the district’s low-income residents.

- Use of the term "affordability". It does not necessarily mean affordable for current Chinatown residents. Rather, the “affordability” of new residential development is leaning to higher-income buyers. Note that 67% of households in this neighborhood are low-income.

- Social mix. While it sounds inclusive and desirable, yet it is not easily archived. It is just another way for higher income people to take advantage of their social capital, and alter the demographics of the low-income community.

Why is it an Issue?

This matter is both serious and urgent because residents are being displaced and forced further and further east. Is this process bad? That is up for debate, as many would argue the neighborhood is being improved. How do we create a place that is tolerant of people from all income levels and void of confrontation? To complicate the matter this is a historic neighborhood with a rich history. This place means a lot to both the residents and the region as a whole. To alter or redevelop what has been a relatively unchanged neighborhood for decades in a difficult task. If places are left unchanged for significant periods of time people tend form attachment at a greater level (11). Gentrification then is really a sudden or mass change in the structure of a neighborhood. The city of Vancouver has tried a number of methods to keep the feel, the vibe, of Chinatown. Limiting building heights and density, requiring developers to contribute to the community and forcing them to accommodate the non-wealthy individuals by providing low-cost housing within their high-end developments (X). How this is being monitored post-construction is anyone's guess but in many cases promises of rental spaces and low-income housing are not being honored (X).

References

(1) Chinatown is people, not just buildings http://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/11175341/DNC/110314%20chinatown%20heights%20report_FINAL.pdf

(2) Zones Of Exclusion: Where poor people are not welcome in the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver (https://sites.google.com/site/zonesofex/)

(3) Anti-Gentrification Activist Goes On Hunger Strike http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2013/03/22/anti-gentrification-hunger-strike-vancouver_n_2936062.html (Via UBC library)

(4) Ethnic Urban Space, Urban Displacement and Forced Relocation: The Case of Chinatown in Montreal http://pao.chadwyck.com/PDF/1369992339673.pdf

(5) Opposition based on gentrification fears; Council allows tall towers in Chinatown http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/864062379

(6) The changing face of Chinatown As shops for the young and hip move in, fears grow they'll push out the old and poor http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/1268801885/fulltext?accountid=14656

(7) Trendy Chinatown worry for poor; Historic Vancouver quarter has drawn hip business owners, a trend some fear will push up home prices and price out the poor http://www.lexisnexis.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/hottopics/lnacademic/?verb=sr&csi=11314&sr=HLEAD(Trendy+Chinatown+worry+for+poor+Historic+Vancouver+quarter+has+drawn+hip+business+owners%2C+a+trend+some+fear+will+push+up+home+prices+and+price+out+the+poor)+and+date+is+April+8%2C+2013

(8) Vancouver’s Chinatown Economic Revitalization Strategy (11 high-level Chinatown Vision directions) http://www.vancitybuzz.com/2012/07/vancouvers-chinatown-economic-revitalization-strategy/

(9) Moving on up: Gentrification in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside http://rabble.ca/news/2012/02/moving-gentrification-vancouvers-downtown-eastside

(10) Vancouver City Council votes to gentrify Chinatown and the Downtown Eastside http://dnchome.wordpress.com/2011/04/19/hahrvot/

(11) Why and how do we become attached to places http://kar.kent.ac.uk/id/eprint/10867

(12) Behind the changing face of Vancouver’s Chinatown http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/british-columbia/behind-the-changing-face-of-vancouvers-chinatown/article7282156/

(13) Is Gentrification Always a Bad Thing? http://thiscitylife.tumblr.com/post/19581371992/is-gentrification-always-a-bad-thing(Via UBC library)

(14) A Tragic Timeline Series: Fix: Searching for solutions on the Downtown Eastside http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/242664050