Course:GEOG350/Archive/2013ST1/Dunsmuir and Georgia Viaducts

Group Members

Patrick Hay & Amy Wong

Introduction

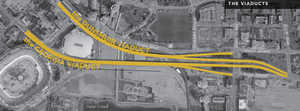

Located in Vancouver, British Columbia, the Dunsmuir and Georgia Viaducts are two elevated roadways that connect East Vancouver to downtown Vancouver. The viaducts were completed in 1972 but with much resistance and debate, they act as the only freeway infrastructure in Vancouver. With an estimated remaining service life of forty years, the high cost of maintenance and surrounding area of under-utilized land has opened up new opportunities and flexible options that would replace and remove the viaducts (Vancouver Viaducts, 2012). According to the City of Vancouver, the intended space would consist of a vibrant entertainment district that would combine both residential and commercial opportunities with opened spaces and parks. However, the potential success of the undeveloped land is not guaranteed because all the replacements may not reflect and be the most beneficial for Vancouver and its’ citizens. Therefore, our study will focus upon how a site-specific mixture of usages and replacements will maximize the utilization of the land and will offer supporting recommendations focused on three main topics: replacement of street networks, affordable housing and mixed use developments and park amenities and green spaces that coincide with other successful freeway inversions projects.

Background

The Dunsmuir and Georgia viaducts are remnants of Vancouver’s past automobile and transportation focus that occurred

within

the city limits. The original Georgia Viaduct was completed in 1915 and accommodated vehicles, horse-drawn carriages and pedestrians. Built along side streetcar tracks (which were never used), the viaduct allowed a continuous east –west passage to and from Vancouver’s downtown peninsula. Initially planned for a prolonged use, the Georgia Viaduct was eventually replaced in 1972 under the Non-Partisan Association (NPA) due to poor and inadequate conditions. Under the administration of the Non-Partisan Association during the 1960’s , Vancouver underwent large scale pro-business and growth-oriented developments that were focused on the expansion and further development of the downtown core (Punter, 2003). During the late 1960’s, an extensive freeway system was proposed to cut through the residential and historical areas of Chinatown on the southern edge of Strathcona and along the north-south side of Main Street to the northern edge of downtown along waterfront to Coal Harbour (Punter, 2003). As a result, the envisioned freeway system was to connect Vancouver’s downtown to the Trans-Canada Highway. In response, however the political organization called The Electors Action Movement (TEAM) was formed in 1968 and challenged and opposed the NPA and their propositions. Backed by a strong professional and academic representation, TEAM rallied for a focus on the virtues of “quality of life”, “the livable city” and “people before property” (Hutton, 2004). United with persistent citywide activists and neighbourhood residents and business owners of Chinatown, Gastown and Strathcona, further expansion and development was under pressure. Consequently, while the Dunsmuir and Georgia viaducts were completed in 1972, the planning and development of the freeway system was abandoned and scrapped by the City Council of Vancouver as a result of growing public opposition. The standalone viaducts have now become symbols the Vancouver’s shifting priorities and have remained distinctive features of Vancouver’s backdrop.

Issues

Proposed by the City Council of Vancouver, the removal of the viaducts was first analyzed in 2011 as part of The Eastern Core Strategy. The initial assessment concluded that there were numerous options to modify the viaducts and both the potential transportation impacts and the condition of the soil contamination in the area were manageable. Outlined in the Strategy, the removal of the viaducts could contribute to the Vancouver region through several key elements: green enterprise, land use and open space, physical and visual linkages and transportation. After a year of public and private consultation, the City of Vancouver released the Vancouver Viaducts Study that analyzed all the options applicable for the replacement and alternation of the viaducts. The study focused on principles focused upon the connectivity of communities, natural systems, urban fabric and revitalization.

In contrast, the removal of the viaducts could also cause various additional and new problems to the area. Potential issues could include an increased congestion of commuters and residents along Prior Street located along Strathcona (causing higher volumes of dangerous traffic), a disruption of the highly efficient Dunsmuir viaduct bike path lane that connects the downtown core to Burnaby, physical obstacles such as the new skate park and skytrain and the cost of the removal of a highly valued piece of transportation infrastructure.

The viaducts are not merely limited to “removal/non-removal”; rather, there are many different facets that are represented by different proposals for what the viaducts might be replaced with and what would be most beneficial for the city and its’ citizens.

Involvement

The number of stakeholders with a vested interest in the resolution of this issue is comprised of public governments, private corporations, and individuals and surrounding communities themselves:

- City of Vancouver: owns the viaducts themselves and the roadway land they occupy;

- Province of British Columbia: owns Andy Livingstone Park (split by Carrall Street), immediately north of the Dunsmuir viaduct and Expo Boulevard;

- PavCo: Crown corporation of Province of British Columbia, owns and operates BC Place and occupying land;

- Concord Pacific: private developer, owning tracts of land south of Georgia Viaduct and in between Georgia and Dunsmuir Viaducts;

- Aquilini Investment Group: private developer, owns Rogers Arena and occupying land

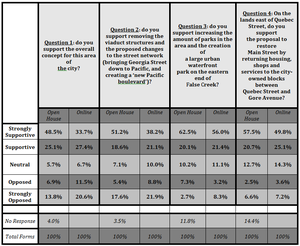

In the summer of 2012, the city presented the Viaduct Plan Concept for public consultation through Public Open Houses as well as an online presentation (presented as “Vancouver Viaducts Summary”). Survey responses were collected from questions regarding public interest in the removal of the viaducts, the creation of more park space along the waterfront, and the renewal of residences and small businesses in the area, as well as their opinions on the urban planning concept on the whole (see sidebar for table of response data)

Additional feedback and commentary was supplied by both supporters and detractors of the proposal. Those who responded with "support" or "strong support" to the survey questions highlighted increased parks and green space, open connectivity between neighbourhoods, and the revitalization of underused land as their reasons for doing so; those who responded with "against" or "strongly against" were chiefly concerned with the additional traffic pressures this would place on Prior St., Venables St. and other False Creek thoroughfares, as well as the usefulness of removing the viaducts (including whether the resources needed to do so could be used for other, higher-priority purposes).

Factors Influencing Core Issues

The issue of the Downtown Viaducts is a relatively urgent matter and its resolution (regardless of outcome) should be of significant priority to the city. This can be demonstrated by examining the consequences of not resolving the matter and leaving the viaducts in their current state. Inaction may impact the city in both direct and indirect ways.

In terms of the former, viaducts in their current form present various financial and cultural burdens and unknown costs (e.g., future earthquake risk). In terms of the latter, the city influences its socio-economic composition by not acting just as much as it might impact composition by choosing to act: in one of the most expensive cities to live in on Earth, with relatively little space for urban development, future pressure to remove or otherwise make use of the viaducts and the land they occupy will only become greater.

Several factors are directly and indirectly making the viaducts an issue requiring solving. These can be summarized as the following:

- Over the last fifteen years, there has been a consistent reduction in the volume of vehicles that enter the downtown through the viaducts (Eastern Core Strategy).As developed under the assumption that urban transportation in Vancouver would expand through a freeway system, the viaducts currently only serve 750 vehicles per lane per hour during peak usage, despite their designed capacity for 1,800 vehicles per lane per hour (Vancouver Viaducts, 2012).

- Maintenance costs for the viaducts are high: elevated structures cost, on average, 5 to 10 times more to maintain that roads at grade. The City of Vancouver estimated that the viaducts will require 8 to 10 million dollars for regular maintenance and structural upgrades over the next fifteen years, and that costs will only increase exponentially as the viaducts age.

- The viaducts separate neighbourhoods, acting as a “physical and psychological barrier” between Gastown, Strathcona, Chinatown, and False Creek and the DTES as a whole (Vancouver Viaducts, 2012).The structures block visibility and divide neighbourhoods, while impairing walkability and commuting underneath.

- Lastly, the land that occupies the viaducts are under-utilized. Before the construction of the viaducts, a community of the city’s black population resided in that area once known to be Hogan’s Alley (Vancouver Viaducts, 2012). Currently, the undeveloped land is not easily accessible and is unused.

The analysis and comparison of responses that solve these problems will guide the resolution of development in Northeast False Creek.

Future Development

On June 26th, Vancouver City Council voted to move forward with the final phase of planning for the removal of the viaducts, allotting $2.4 million over two years to build a workplan and conduct a financial analysis. While the final decision to remove the viaducts has not yet been made, the agreement to consult and study the potential implications of viaduct removal and land usage represents the last time that planning and consultation will take place before such a decision (Dunsmuir and Georgia Viaducts, 2013).

Project Timeline

-

- 2013-2015: Develop viaducts area plan to support negotiations with land owners and complete initial designs of streets and parks.

- 2015-2017: Complete rezoning, legal agreements, and finalize street and park designs

- 2017-2019: Construction and viaduct removal occur simultaneously, taking 18-24 months.

Project Guidelines

- Reconnect Historic Communities and False Creek: The viaducts create "a physical and visual barrier" between Chinatown, Gastown, Strathcona, Thornton Park, Victory Square, the DTES, and the waterfront. Removal provides an opportunity to explore how these communities connect to the waterfront and each other.

- Expand Parks and Open Space: Increase the amount of parks and open space; viaduct removal and a more efficient street network will result in a potential increase of 13% (~3 acres) of parkland, and gives the option of a more coherent open space system allowing more flexible public events and programming.

- Repair Urban Fabric: Removal of viaducts allows for restoration of shops and mixed-use development of Main Street corridor between Quebec and Gore streets after being demolished when the viaducts were being constructed.

- Explore Housing Development and "Place-Making Opportunities" on City Blocks: Based on development patterns of Chinatown and False Creek, development of housing on city owned blocks could generate approximately 850,000 square feet of density, representing 1000 units (and 200-300 affordable housing units). Height, density, unit mix, and other development characteristics will be determined in next two year planning phase.

- Create Vibrant Waterfront District: Ensure future building in the area creates mixed-use recreational and residential district with consistent urban design principles, seamlessly tying into to the upcoming Creekside Park Extension

- Increase Street Network Efficiency: By replacing viaducts with new network of at-grade streets - these require bi-directional connection (from Georgia to Pacific Boulevard, with east-west movement directly to Quebec, Main, and Prior Streets)

- Improve Connectivity between Downtown, NEFC, and the Waterfront: Replacement street network would optimally, retain sufficient goods movement routes to/from downtown, maintain vehicle capacity and transit routes, and integrate future NEFC development to downtown.

- Enhanced Pedestrian and Cyclist Movement: Future street network would have to improve on the Dunsmuir Viaduct which currently serves cyclists moving east-west. May possibly develop dedicated pedestrian/bike bridge to ensure this.

- Develop a Fiscally Responsible Approach

- Engage Residents and Stakeholders in a Meaningful Way

Resolution

There are two major decisions to consider in the resolution of this issue. The first is binary: keep the viaducts as they are and continue supporting the infrastructure as expected, or remove the viaducts entirely (assuming, of course, that no one would let the viaducts fall apart on their own). The second is more complex: to decide what should replace the land occupied by the viaducts, of which there are several proposed options, both informal and formal (inclusive of the option to do nothing more than is required; that is, replace elevated roadway with at-grade road, and leave remaining public and private land undeveloped entirely).

We argue that by replacing the land occupied by the viaducts with various options would benefit Vancouver in the long term in contrast to keeping them in their current condition. Our resolution and recommendations are guided by the project guidelines previously outlined and case studies that have successfully benefited from their urban freeway removal.

Similar Projects

While the issues behind urban freeway removal have been debated throughout the decades, there are numerous examples that have successfully resolved their disinvestments. Although Vancouver and the Dunsmuir and Georgia viaducts have their own specific concerns and underlying issues, it is important to learn how to positively benefit from other removal projects by considering all relevant outcomes when deciding upon a future of the viaducts.

Embarcadero Freeway, United States

In San Francisco, the Embarcadero Freeway was demolished in 1991 after decades of debates and consequently the1989 earthquake that further catalyszd the removal (Mohl, 2012). Once highly used for automobile transportation, the removal resulted in a positive environment for all types of residents and visitors. The Embarcadero Freeway was replaced with street-level boulevards, new developments and parkland that rejuvenated urban neighborhoods that were once disconnected. The conversion opened up accessibility to San Francisco Bay and helped revive San Francisco’s waterfront through business developments and attractive cultural activities (Mohl, 2012). The space also blended pedestrian walkways and bicycle corridors with a popular streetcar line. Once isolated by the freeway, the greenway conversion predominately benefited the waterfront area through increasing the amount of visitors and investors (Mohl, 2012). The land that the freeways once occupied also opened up new opportunities in residential and commercial developments. An additional 900 housing units were to be built, half of them to be affordable for low and very low income households and adjacent office and retail spaces (Cervero,. & al).The success that was experienced in the removal of the Embarcadero Freeway was not caused by the simple replacement of the freeway but a combination of key elements: proper design strategies that included a “complete” street design that accommodated all users and modes of transportation; the management, mitigation, monitoring of reductions of roadway capacity throughout a long-term commitment; promoting civic conversations to deal with inevitable sacrifices and the understanding of the “larger picture,” in which the removals are only an element of a vision to enhance the quality of life, sustainability and economic opportunities (City of Seattle, 2008).

Cheong Gye Cheon, Korea

The Cheong Gye Cheon elevated freeway located in the heart of Seoul, Korea, was demolished and replaced by an urban greenway project. Under the then-Mayor, Myung-Bak Lee, the Cheong Gye Cheon freeway was torn down in 2003 and then converted into an appealing urban amenity (Kang, 2009). Aimed to improve the restoration of urban parks and public amenities, the freeway-to-greenway conversion were to enhance the quality of residing within the downtown core. Backed by Myung-Bak Lee, who stated, “we want to make a city where people come first, not cars”, the land was replaced with a retrieved stream, linear park and bicycle pathway (Kang, 2009). This was beneficial for the city because the Seoul Development Institute had found that the land values that were adjacent to the transformation had increased by an average of 30% and helped attract more than 90,000 visitors a day (City of Seattle, 2008). Automobile traffic passing through the downtown was also reduced when a rapid bus transit system was put in place and helped reduced nose pollution and carbon emissions (City of Seattle, 2008). Furthermore, the restoration of the stream and enhanced open space accessibility helped improve the quality of life of both residents and visitors of the city. In conclusion, Seoul’s greenway investment illustrated the possible economic and environmental benefits that can result from the success of urban design and showcases how the removal is paramount for the platform of Myung-Bak Lee’s vision in the future of Seoul (City of Seattle, 2008).

Recommendations

Previous urban freeway removals have shown numerous additional social and environmental benefits that have included the reduction of carbon emissions and nose pollution, improved quality in the environment, increased safely of alternative modes of transportation, increased connectivity of neighbourhoods, economic renewals and an overall more effective usage. Therefore, our recommendations will mirror certain important case study features and will focus on three main topics: replacement of street networks, affordable housing and mixed use developments and park amenities and green spaces that we believe are the most beneficial to Vancouver.

Replacement of Street Networks

First and foremost, removing the viaducts necessitates a plan to accommodate for leftover traffic usage.

Constructing a viable replacement street network plan is essential to making the most of NEFC's potential. Based on recommendations supplied by architectural firms DIALOG, PWL Partnership, and Beasley & Green, we propose that after removing the viaducts, Georgia Street be extended to to Pacific Boulevard on a slope (this is feasible at a ~5% grade), and Pacific Boulevard is joined up with Expo Boulevard, re-routing it north of the Skytrain Guideway. This, in essence, would fulfil Georgia Street's suggested role of "ceremonial function" as well as making Pacific Boulevard a two-way, east-west thoroughfare. Study has shown that this street network will be well-suited for future traffic capacity (including full-size trucks and event traffic bound to/from Rogers Arena/BC Place) and provide access to future development sites. Furthermore, this street network plan allows for short term, quick viaduct removal, rather than the 15-20 year period envisioned in the 2010 Vancouver transportation study (Dunsmuir and Georgia Viaducts, 2013)

In respect to the potential increased congestion along other roadways such as Prior Street, case studies have shown that this “spillover” traffic can be efficiently absorbed. Traffic can be easily accommodated by other modes of transportations and alternative routes. This can be done with appropriate traffic and land management use strategies that would decrease traffic on a single route. In a study focused on the removal of the Harbor Drive freeway, Portland, there were minimal negative traffic impacts due to proper traffic management and effective street grids (City of Seattle, 2008). This included the conversion to one-way streets and reduced speed limits that ensured the safely of pedestrians and cyclists (City of Seattle, 2008). In relation to Vancouver, this can be done to help reduce the potential congestion and increase the safely along new streets but particularly along Prior Street. With alternative routes, existing modes of transportation (pedestrian walkways and bike lanes) can be further incorporated to allow travelers the option to choose the most convenient mode for their trip. Freeway removals do not cause a major shift in transportation but rather, the patterns of transportation will be impacted.

Affordable Housing and Mixed Use Development

The removal of the viaducts frees a critical parcel of land: the rectangle bordered by Prior and Union Streets, and Quebec and Gore Streets, centred around Main Street. This land is owned by the City of Vancouver (as opposed to private developers) - conceptual planning shows that, at 7 acres, trust partnership developers could build over 850,000 square feet of mixed-use commercial and residential development, representing ~1000 housing units, of which it was assumed that a minimum of 20% would be marked as affordable non-market housing.

With this in mind, we recommend that the city challenge itself and develop mixed-use commercial and residential sites with at least a 75% unit mix of affordable housing. The city has an opportunity to encourage a socially progressive approach by providing shops and services as well as modernized high-density housing stock. Small businesses on street level paired with a healthy mix of affordable and market housing, accompanied by residential green spaces and other design aesthetics would revitalize the Main Street "gap" in the way that the city and residents of surrounding neighbourhoods would approve of.

Vancouver is notable in that it has been openly encouraging developers to make at least 20% of their unit base affordable housing (with at least 50% for families) since 1988 - the city does not force developers to do so, but incentivizes them by raising density ceilings and providing other development amenities. While Vancouver has the most formalized and integrated system of affordable housing programmes across major Canadian cities, affordable housing units are still being built below target capacity levels (in no small part to the difficulty in constructing such housing with virtually no funding to municipalities from the federal government) (Mah and Hackworth 2011). Ley and Dobson (2008) claim that the development and promotion of affordable housing is a principle tactic of mitigating gentrification, especially in Vancouver. Bryant (2003) cites evidence that social housing is imperative for both mental and physical health. Those without reliable housing suffer from far worse health outcomes, and furthermore, this fact is not limited to homeless persons; several studies have shown that individuals who rely on transient-focused housing (hostels, shelters, etc.) suffer from increased musculo-skeletal and respiratory illnesses and infections, both acute and chronic. Most alarmingly, Bryant notes that Canada has the most privately-dominated housing market, with the least government support for social housing, in the western world, other than the United States - it is this fact that demonstrates the necessity of developing social housing on a local level.

Francis (2010) found that African refugees, in particular, suffer from availability and affordability housing crises in Vancouver that forces them to accept substandard housing. 73% of refugee claimants (RCs; by definition usually arrive in Canada as single parents with 1-2 children and receive virtually no federal support) experience at least one distinct period of homelessness since arriving in Vancouver. Given the historical significance (and the generally accepted social injustice) of the demolition of Hogan's Alley during the construction of the viaducts (and thus the city's only black neighbourhood), and in much the same way that the city has worked with women's organizations to construct safe homes in the DTES, the city might want to consider partnering with a Vancouver based refugee advocacy-group to manage the acquisition of some level of social housing for vulnerable African refugees who may be awaiting work permits or permanent resident status. Finally, we would recommend that the city consider installing a memorial (or other type of tangible aesthetic) near the original site of Hogan's Alley in order to commemorate the loss of a historic Vancouver neighbourhood as well as demonstrate the unification of proper urban planning principles and cultural diversity.

Park Amenities and Green Spaces

The land occupying beneath the viaducts should be replaced with the reintroduction of water and natural systems through a linkages of parks and public open spaces. In relation to the case study of Cheong Gye Cheon,

the conversion from freeway-to-greenway could be beneficial to Vancouver through enhancing the accessibility of open spaces and improving the restoration of public amenities. Similarly to the Embarcadero Freeway demolition, the removal of the viaducts would further help achieve the City of Vancouver’s initiative in improving the quality of life and becoming the leading city in sustainability outlined in The Greenest City 2020 Action Plan (Vancouver Viaducts, 2012). With a strong network of parks and green spaces, new recreational opportunities, natural amenities and leisure activities would be available for the public. These factors would help sequester carbon emissions and reduce greenhouse gases and further promote Vancouver as a sustainable community (Condon, 2010). With the addition of a water and stream system, conjoining paths organized around the water system would allow for pedestrians and cyclists to access various points of the opened space (Condon, 2010). Without the use of an automobile, these paths would provide a relaxing, more comfortable and shaded mode of transportation and could possibly help reduce the heat island effect experienced in the

downtown core(Condon, 2010). Not only would the park and green space provide an aesthetic benefit, the new area would expand and connect to the existing Livingstone Park, thus resulting in a coherent space that would include a relocated skate park. Without the physical barriers of the viaducts, commuters can easily access surrounding communities and waterfront amenities of False Creek through and around the green space. This would also strengthen linkages between the communities of Chinatown, Gastown, Strathcona, International Village, DTES and False Creek through reviving the connectivity of these communities. In relation to the Embarcadero Freeway, the coast along Northeast False Creek could also experience a renewal along the land that is owned by Concord Pacific. Currently, home of the relatively subdued Plaza of Nations and a large opened parking lot area, the expansion of green space would help extend activities and attract more people towards the waterfront. In addition, by replacing the concrete parking lot situated east of the Plaza of Nations, the seawall can be expanded and accommodated with green space to run alongside the coastline of Northeast False Creek to the Olympic Village. With the reintroduction of natural and linked systems of parks and green spaces, Vancouver would greatly benefit in establishing itself as one of the top greenest cities in the world. Further attracting more people and activities, this area will become a lively environment that could include a variety of new innovation in urban design focused on sustainability, introduction of community gardens, orchards, playgrounds, sport fields, water parks and more.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we believe that by replacing the viaducts with effective street networks, affordable housing and mixed use developments and park amenities and green spaces will be most beneficial in establishing Vancouver as one of the most sustainable and liveable cities in the world. The viaducts have been features of Vancouver’s backdrop for decades, but in terms of both form and function, they have not integrated themselves into Vancouver’s vision of sustainability and improved quality of life. Rather, they have caused a disconnect between communities, additional high costs, inefficient automobile capacity and under-utilized lands. Now as it ages, a window of opportunities has opened up to redevelop the last remaining land along False Creek. The success of the urban freeway removal will further rely upon a longitudinal commitment focused on proper management and monitoring, public engagement and suitable recommendations in the far future.

Bibliography

- Cervero, R., Kang, Junhee & Shively K. (2009) From elevated freeways to surface boulevards: neighborhood and housing price impacts in San Francisco. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 2(1), 31-50. doi: 10.1080/17549170902833899

- City of Seattle. (2008). Seattle Urban Mobility Plan: 6 case studies in urban freeway removal. Seattle. http://www.seattle.gov/transportation/docs/ump/06%20SEATTLE%20Case%20studies%20in%20urban%20freeway%20removal.pdf

- Condon, P.M. (2010). Seven Rules for Sustainable Communities: Design Strategies for the Post-Carbon World. Washington: Island Press. Print.

- "Dunsmuir and Georgia Viaducts and Related Area Planning". (2013). City of Vancouver. http://former.vancouver.ca/ctyclerk/cclerk/20130626/documents/rr1.pdf

- "Eastern Core Strategy".(2011). City of Vancouver. http://vancouver.ca/docs/eastern-core/core-strategy-council-report.pdf

- Francis, Jenny. (2010). Poor housing outcomes among African refugees in Vancouver. Canadian Issues (Autumn): 59-63.

- “Georgia and Dunsmuir viaducts study”. (2012). City of Vancouver. http://vancouver.ca/home-property-development/viaducts-study.aspx

- Hutton, T. A. (2004). Post-Industrialism, Post-Modernism and the Reproduction of Vancouver's Central Area: Retheorising the 21st-Century City. Urban Studies (Routledge), 41(10), 1953-1982. doi:10.1080/0042098042000256332

- Kang, C., & Cervero, R. (2009). From Elevated Freeway to Urban Greenway: Land Value Impacts of the CGC Project in Seoul, Korea. Urban Studies, 46(13), 2771-2794.

- Ley, David and Cory Dobson. (2008). Are there limits to gentrification? The contexts of impeded gentrification in Vancouver. Urban Studies 45, 2471-2498.

- Mah, Julie, and Jason Hackworth. (2011). Local politics and inclusionary housing in three large canadian cities. Canadian Journal of Urban Research 20, (1) (Summer): 57-80.

- Mohl, R. A. (2012). The Expressway Teardown Movement in American Cities: Rethinking Postwar Highway Policy in the Post-Interstate Era. Journal Of Planning History, 11(1), 89-103. doi:10.1177/1538513211426028

- “Public Consultation Summary”. (2012). City of Vancouver. http://vancouver.ca/home-property-development/viaducts-study.aspx

- Punter, J. (2003). Vancouver Achievement: Urban Planning and Design. UBC Press. Retrieved from http://site.ebrary.com/lib/ubc/docDetail.action?docID=10130611&p00=vancouver%20achievement

- “Vancouver Viaducts Summary”. (2012). City of Vancouver. http://vancouver.ca/docs/eastern-core/viaducts-june2012.pdf