Course:GEOG350/2013ST1/DTES Gentrification

Gentrification in the Downtown Eastside - Introduction

The purpose of our project is to define gentrification, with a focus on "commercial gentrification", and explore the role of this process in the Downtown East Side of Vancouver. The neighbourhood we have selected is spatially enclosed by the following streets: West Cordova Street, Abbott Street, West Pender Street, and Columbia Street. We will begin by providing a history of the DTES in general, and subsequently provide details of the demography and built form of our chosen neighbourhood. Following this we will define gentrification and in more thorough detail discuss the process "commercial gentrification" which is directly affecting our neighbourhood at this time. Upon analysis of the problems commercial gentrification, and also gentrification at large create, we will examine tested solutions as well as consider some of our own ideas towards what can balance the drastic and dynamic changes occurring in the Downtown East Side.

History

The Downtown Eastside (DTES), Vancouver’s oldest residential neighbourhood was once a major hub for the city’s commercial and industrial activity. In the mid-19th century it was a residential area for those working in BC’s resource economy, notably logging and fisheries. Seasonal workers would temporarily live in hotels primarily concentrated in the Downtown Eastside, which resulted in a growth of bars and services in the neighbourhood in order to serve the resource industry workers [1]. As a result, the area became “an extension of the province’s resource economy with its canneries, sawmills and meatpacking plants” (Hasson and Ley: 1994) [2] and was for a time known as “skid road” because of its association to the logging industry.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the DTES was largely a working class neighbourhood as many families moved away to other neigbourhoods in the city. In the early 20th century, the Downtown Eastside became the heart of the city and home to successful retail businesses, the city’s first library at the Carnegie Community Centre, the first department store –Woodwards - on Hastings Street, the first City Hall on Main & Hastings, as well as the BC Electric Interurban System streetcar terminus at Hastings & Carrall. This vibrant community developed in the first half of the century. However, after the Second World War in the wake of developments in other parts of the city and a westwards shift of the Central Business District, the neighbourhood’s landscape began to change. The DTES experienced a reduction in daily visitors by the thousands, as well as severe economic marginalization with an influx of low-income residents. The termination of the streetcar service and North Shore Ferry Service followed in the late 1950s resulted in even less visitors traveling through the area, businesses began to decline, and an increased number of single low-income residents and deinstitutionalized patients from mental health facilities occupied the neighbourhood, creating the need for shelters, housing and social services --problems which persist and prevail today.

According to Ley and Smith (2003) [3], from 1970 onwards the DTES “consistently suffered multiple forms of deprivation (there are about 140 separate social agencies and non-profit organizations operating in the neighbourhood)”. By the late 1980s, the situation had deteriorated even further with a spike in alcohol and serious drug use by residents, due to the increased availability and reduced cost for street drugs from an overall worldwide increase in illegal drug production. In 1992, the Woodwards department store went out of business along with several others in the area, pushing the neighbourhood into the deepest downward spiral (Blomely, 2004) [4]

The significant social, economic, political and spatial changes the Downtown Eastside has experienced in the last century has transformed the neighbourhood today into what some call Canada’s “poorest postal code”, ridden with poverty, drug use, sex trade, crime and recently, and now, massive inner-city re-development plans by the City - some of which have resulted in intense gentrification in several areas of the neighbourhood.

Demography

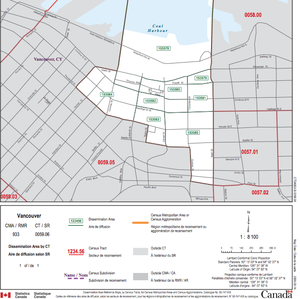

Our study area lies with census tract 0059.06 according to Statistics Canada. Unfortunately, we could not find exact data for the specific area within our boundaries but the following data for the specified census tract includes our study area and is from the 2006 census [5] , unless otherwise noted.

- From 2001 to 2006 the CT experienced a 24% growth in population from 4,993 residents to 6,205.

- The population density per square kilometer Is 10,504.5 within a total land area of 0.59 square km.

- 74.4% of the population are non-immigrants however 21% are part of a visible minority (20% sample data) .

- 5,715 residents over age 15, 3,055 listed themselves as not part of the labour force and the unemployment rate was at 13.9 %.

- Median income in 2005 for persons 15 years and over was $10, 884.

- Of 5,715 persons aged 15 and over, 2,080 do not possess educational attainment of a certificate, diploma nor a degree.

The reason we note these demographic statistics is threefold. Firstly, the 24% increase in population proves the growing popularity of the area for residents. High population density in a run down area requires the process of gentrification through new construction and refurbishing of old buildings for newer residents. This however has been shown to increase rents in older housing units, pushing out lower income residents in the area. Secondly, there is a large portion of visible minority individuals simultaneously occurring with low employment rates and a low median year income of $10, 844 in 2005. The combination of these factors draws a graphic mental image of the character of the neighbourhood. Presumably there is a connection between low employment, low income, and visible minorities in the population. The DTES of course, is also well known for it's prevalence of drug issues, though not addressed in these statistics, is evident because of the presence of a safe injection site in our neighbourhood. Thirdly, approximately 1/3 of the population 15 and over do not possess formal post secondary education. Many studies have linked the connection of low education levels to low wage employment, which is clear in these statistics.

Our Neighbourhood

Built Form

Spatial Bounds

- Northern boundary: West Cordova Street

- Western boundary: Abbott Street

- Southern boundary: West Pender Street

- Eastern boundary: Columbia Street

Contains

- Save-on-Meats

- Pidgin Restaurant

- The Bourbon

- The Army and Navy Department Store

- Pigeon Park

- the Vancouver Police Department

Surroundings

- To the west there is Woodwards and the Dominion Building in Victory Square

- To the north there are Gastown developments, a lively restaurant and bar scene, the train tracks, Portside Park and Crab Park

- To the east is safe injection site, the Main and Hastings Community housing society, the DTES Women's Centre (juxtaposed by a large furnished gastown apartments building), and Oppenheimer Park

- To the south is the Sun Yat Sen gardens, the Chinese Cultural Centre, both the Georgia and Dunsmuir viaducts, blocks of high-rise developments, and Andy Livingstone Park

- According to www.walkscore.com our neighbourhood scores very high with regards to quick accessibility to nearby amenities via walking, biking, and/or transit systems [6]

While the Downtown Eastside is often referred to as a neighbourhood in and of itself, there is much controversy surrounding the "actual" boundaries of the area due to the ambiguities associated with the word "neighbourhood". As is noted by geographer George Galster, many definitions of neighbourhood "...presume a certain degree of spatial extent and/or social interrelationships within that space and they underplay numerous other features of the local residential environment that clearly affect it's quality from the perspective of residents, property owners, and investors." (Galster, 2001)[7] As we have mentioned, our area of study is spatially bounded by Carrall, Abbott, West Cordova and West Pender street. While these street boundaries indicate solid constraints visually to any individual looking at the built form of our neighbourhood space, these bounds do not provide information on residents personal identifications with place. (Barnes and Hutton, 2008)[8] In reality, neighbourhoods must be addressed with regards to both space and place, the built form and different people's attachments and detachments from the area. Our chosen neighbourhood within the Downtown Eastside is found at an intersection of popularly named subsections by Vancouver: Victory Square, Gastown, and Chinatown. Our interest in this area of the Downtown Eastside was sparked by the social unrest and controversy surrounding commercial gentrification evident in media references to Pidgin Restaurant, Save-on-Meats, and the various protests towards these restaraunts.

What is Gentrification?

Definition of Gentrification

According to Sage Knowledge's online reference encylopedia of geography, the term "gentrification" is traditionally traced back to British sociologist Ruth Glass, who used it in 1964 to describe the movement of middle class people into inner city neighbourhoods and fixing up derelict housing, causing the displacement of lower income working people in London. (Warf, 2010)[9] It is only over the past few decades however that this term has come into popular use and circulation in not only research but also the popular media. Over this time period, the term has evolved to encompass not only residential displacement and renewal, but also the effects of cultural and infrastructural investment. It has been said that "gentrification has come to be regarded as the foremost expression of both a culture of consumption and a new, postmodern aesthetic lifestyle." (Fillion, 1991; from Current Sociology, 1995)

How It is Affecting the DTES

The exorbitant cost of living in other areas of Vancouver causes many middle class working people to look for their most affordable options while still achieving the lifestyle of consumption they desire. Over the past few decades developers have promoted their housing units to this market, slowly encroaching into the DTES area as they build from external bases of infrastructure. Inner-city regeneration began in the late 1960s in the efforts to eradicate “skid row” and revitalize the area. Plans for massive re-development of the DTES were backed by a consortium of developers, business interests and multiple levels of government (Smith, 2003) [3]. Although Gastown and Chinatown were the areas of initial focus, the energies of this urban ‘revitalization’ soon shifted to include the other DTES neighbourhoods.

As Barnes and Hutton (2008) [8] put it: “inner-city regeneration partly prompted by new economy activities has increased pressures for gentrification in the Downtown Eastside, decreasing the supply of affordable housing”. In fact, housing opportunities for low-income individuals in the DTES became a central concern in the 1970s as housing prices in other parts of the City began to rise. Despite a growth in non-market housing at this time, the DTES still faced a steady decline in Single Room Occupancy (SRO) housing units over the course of the 1980s and 1990s. In response, in 1995 The City of Vancouver prepared a housing plan in the DTES with the aim to introduce into the neighbourhood “a wider mix of housing types, tenures, households and socio-economic classes… brought about by increasing the level of market housing in the area from 2,500 to 4,500 units” (Smith 2003) [3]. However, this allowed more affluent households to settle in the area and intensified pressures of upgrading the DTES. According to Smith (2003), [3] this process also led to heightened socio-spatial polarization between low-income residents and the more affluent class moving into the neighbourhood.

The Issue: Commercial Gentrification

Definition of Commercial Gentrification

It has been predominantly noted in the literature on gentrification that housing dynamics play a major role. Where the commercial dimension of gentrification is mentioned, often times only the role of residents as consumers has been noted to play a large role in gentrification. Much research has been performed by David Ley advocating for consumption theory in concert with how gentrification manifests itself in Vancouver. For example, Granville Island is a former industrial site turned into a commercial and residential island of creativity, "consumption and play". (Bain, 2010) [10] Rankin argues that, "With a few exceptions, what is absent from the literature on commercial change is an analysis of the types, motivations, and experiences of commercial establishments in gentrifying neighbourhoods—especially those at risk of displacement—or strategies for retaining those businesses serving the needs of low-income and ethnically mixed residents." (Rankin, 2008) [11] Notably, during the 1970's and 80's when gentrification took hold as a popular term it referred almost exclusively to low income-renters being involuntarily displaced. Since then academics like Shiflet have broadened the conceptualization by writing, "However, gentrification can also refer to the replacement of non-residential tenants – including commercial businesses and nonprofit organizations. Put simply, commercial gentrification is a process of lower-income producing businesses or organizations being replaced with higher-income producing businesses. Like the broader gentrification definition, the process of change must include involuntary displacement of lower-income tenants, upgrading of the built environment and a change in community character." (Shiflet, 2006) [12] Since commercial gentrification is an increasingly common consequence in the revitalization of urban centres, it is interesting to investigate in our neighbourhood as it is a combination of consumerism in hand with new restaurants and other businesses causing property costs to rise pushing out lower income residents as well as lower income business owners. With consideration to economic system change, Howsley has proposed that "...gentrification typically affects a whole local area, making commercial and residential components mutually dependent.", a paired process of interdependence. (Howsley, 2003)[13] The author also notes in their case study findings in a Portland neighbourhood that a particular balance between residents of the neighbourhood and visitors must be maintained for full-rounded gentrification.

How It Is Affecting our Neighbourhood

Today, re-development in the DTES continues and we are facing increased pressures for gentrification as new businesses, shops and restaurants catering to the higher socio-economic classes enter the area. This process is largely being driven by entrepreneurs looking to capitalize on lower costs as trendy living expands from other regions of the city (ex. Gastown). Specifically, two new upscale businesses that have endured severe recent anti-gentrification protests are Save on Meats and Pidgin restaurant. The former is a high-profile butcher shop located on Hastings St between Abbott and Carrall St, and the latter is a new restaurant located across the street from Pigeon Park on Carrall St, a popular drug dealing spot and hangout for some of the DTES’ lower income residents. Both businesses have made efforts to integrate into the neighbourhood. For example, Save on Meats donates profits to neighbourhood charities, as well as offers a program that gives out warm meals out to local residents in exchange for tokens, which can be purchased by the public online or at the store. This venture has been largely successful and recently expanded to include giving out warm clothes for tokens. On the other hand, Pidgin owner Brandon Grossutti employs DTES residents in an effort to make “two parts of the city be able to come together” (CBC, 2013) [14]. Nonetheless, there has still been an outbreak of protests in front of the businesses by residents and city anarchist groups, one even going so far to label Save on Meats as the “poster child of gentrification” [15]. The Vancouver Foundations' continues their intentions to follow through with the Carnegie Community Action Project (CCAP) despite anti-gentrification protests in the DTES as well. [16] Despite Pidgin Restaraunt's and Save on Meat's best efforts to support the existing neighbourhood community while building a brighter future simultaneously, residents continue to protest. Evidently, although these commercial sites are attempting to integrate into the neighbourhood, their high profiles threatens the lifestyles of a large portion of DTES residents. As quoted by Jean Swanson, co-ordinator of the CCAP, “Charity isn’t going to solve the problem. We need higher welfare rates. We need housing people can afford” (CBC, 2013). [14] Therefore, it is possible they see the development of new commercial infrastructure the neighbourhood as bolstering the new residential developments locally, magnifying the effects of gentrification.

Why Is This An Issue & Why Should We Analyze It?

Although Vancouver city planners’ redevelopment strategies area geared towards creating a socially mixed neighbourhood in the DTES to lift low-income areas out of poverty, protesters are just not seeing it in the same light. Local residents are advocating that new developments be used to provide social housing units instead, which is something the neighbourhood is severely lacking (CBC: 2013) [14]. The gentrification of our study area is therefore clearly an issue because DTES locals are finding themselves displaced in their own neighbourhood with the onset of new upscale businesses and housing catered towards the affluent, and few towards lower-income residents. Socio-spatial polarization is a significant result of gentrification in the DTES. (Smith 2003) [3] The surrounding population of Vancouver around the DTES stigmatizes this neighbourhood as chronically poor and the root of most problems, even though Vancouver chose this area as the place to confine it's problems. In the cities efforts to become a "world class" city neoliberal policies are being embraced by all three levels of government, and going largely unquestioned as they polarize Vancouver. (Dobson, 2004) [17] As Dobson also points out, "By stereotyping the entire neighbourhood in this way, and then trying to eradicate the cause of the problem, society tends to isolate the residents even more and further exacerbates the social ills of the city as a whole." (Dobson, 2004) [17] Over the past few decades "the language of regeneration the negative elements of gentrification have been relegated to the periphery, with the process itself being recast as a positive and necessary urban process", and only recently has the term been acknowledged once again. (Dobson, 2004)[17]

Solution Efforts

To balance the ongoing drastic and dynamic changes occurring in the Downtown Eastside partially caused by commercial gentrification, solutions should focus on mitigating socio-spatial polarization of local residents, as well as improving the reduced purchasing power and limited choice in the housing market from which a vast majority of low income residents in the area suffer (Barnes & Hutton, 186)[8]. The right approach requires a collective, multi-faced response from both public and private sectors, as well as civic participation from local residents to enrich the pool of social capital. “What is really needed…is community dialogue and ‘place-based,’ grassroots planning to ensure the area grows to accommodate existing residents and economic opportunities brought by new businesses”, says executive director of the Hastings Crossing Business Improvement Association, Wes Regan. “We have to keep a balance of what’s coming into the neighborhood,” he said. (The Province, 2013). [18]

Government Approach

Sustainable long-term changes emphasizing primarily on the re-development of the local economy, residential setting, and social services are necessary to mitigate the ramifications of commercial gentrification. Recent government policy and planning processes aim to target these sectors, as can be seen in the City of Vancouver’s ‘Downtown Eastside Local Area Plan’. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; invalid names, e.g. too many The project, which began in 2011 and is currently in the last year of the planning process, will be developed in partnership with the DTES Neighborhood Council (DNC), Building Community Society (BCS), and the Local Area Planning Committee. It’s goals include as follows: “The LAP process aims to ensure that the future of the DTES improves the lives of those who currently live in the area, particularly the low-income people and those who are most vulnerable, which will benefit the city as a whole. Throughout the planning process, the social, economic and environmental impact of current and future policies on the low-income community will be considered. Issues such as the pace of change and how to improve the lives of residents will be points of discussion.” [19]

Through a flexible framework to guide change and development via long range and short-term ideas, the Plan also offers a range of community engagement opportunities throughout the planning process to collect ideas and feedback from Vancouverites on the neighborhood’s redevelopment. “Efforts will be made to ensure that everyone in the area has a chance to put their ideas forward”, in attempts to “overcome barriers to participating that stem from income, race, language, gender, age and mental or physical health concerns.” [20] As aforementioned, we believe the answer to correcting ramifications of commercial gentrification mainly lie in improving the DTES’ local economy, residential setting, and social services. These aspects are included in the DTES Local Area Plan, which has a 10-Year Objective strategy to reach its goals. In regards to boosting the local economy, with a current unemployment rate of 11.3% in the neighborhood, the Plan’s strategy will focus on “fostering innovative partnerships to develop a more vibrant, successful and inclusive economy” through: retaining the existing 2,800 business in the area, facilitating a 3-5% growth in businesses and a 50% reduction in vacant storefronts, attracting at least two affordable grocers to serve local residents, and facilitating 1,500 new jobs (to employ 50% of currently unemployed people). [21] Next, the residential improvement aspect of the Plan aims to develop 800 new social housing units, upgrade the condition of 1,500 SRO units, support improved affordability for 1,650 low-income residents through new and existing rent subsidy programs, and create a further 1,650 new units of affordable market rental housing [22] . These objectives are part of the plan’s “3 Keys to Housing” strategy focused on ‘affordability, condition, and support’:

Finally, improving the health and well-being of the DTES means addressing significant health and social inequalities and working collectively to secure social assets in order to ensure every resident has their basic needs met. Actions include supporting projects promoting inclusion and sense of belonging and safety through grant funding, protecting low-income assets from gentrification and displacement, increasing equitable access to quality and inclusive health, social and community services, decreasing child vulnerability, and improving the access, quality and nutrition of charitable food [23] . The health aspect of the Plan lies on the following concept of ‘Building Blocks of a Healthy City For All’ :

Our Proposed Solutions

In addition to the City of Vancouver solutions aforementioned, our proposed solutions expand on these plans, primarily focusing on improving local employment, social-well being of residents, and social housing. While many manufacturing jobs have been taken out of the city in response to the creative culture being promoted by neoliberal policies, there is inevitably a job crisis. However, one possible solution could be for more restaurants such as Save-On-Meats and Pidgin Restaurant across the city to provide more jobs to those unemployed former DTES residents. This aspect is also outlined in the DTES Local Area Plan aforementioned, and it exemplifies how a collective approach and effort between local residents and businesses can work towards creating a more balanced Downtown Eastside. Furthermore, perhaps instead of secluding Vancouver's problems as was done in the 70's and 80's to the concentrated area of it's Downtown Eastside, health and social services, as well as social housing units for the low income, could be expanded city wide as to encourage residents seeking these services to disperse into the city. This is not to say we want to push them out of their neighborhood, as many surely consider it their home, however it is just another alternative worth considering concerning improving the social well-being of DTES residents as well an attempt to reduce concentrated socio-spatial polarization. If the poor and addicted were spread throughout the city into different social housing units with necessary facilities locally available, perhaps this could assist in improving the issues. Without such a large support network of other troubled individuals, more people could rise out of adversity. One problem with this, however, is that many of the services provided in the DTES are from non-profits organizations, not the government. Without large funding it would be difficult for services to expand or to afford moving to a new location. With government assistance however, perhaps this could be more plausible. Along with the above ideas, commercial and residential gentrification's adverse affects could possibly be reduced or even mitigated. If production of higher class housing units happened simultaneously with social housing (a re-entry of the government into providing city services, not just private development based on neoliberal policies), perhaps the poor would not feel so pressured out of their homes, even as the cost of living inevitably rose. Perhaps in order to attain some of these forms of social housing, residents would have to meet some sort of qualifications, such as volunteering regularly if they were unable to yet find a job, or somehow giving back to their community. This may aid in changing many people’s negative conceptions associated with the DTES and its residents to a more positive one.

References

- ↑ UBC Learning Exchange. 2005. http://www.learningexchange.ubc.ca/files/2010/11/overviewdtes2016.pdf

- ↑ Hasson, S. and D. Ley, 1994. Neighbourhood Organisations and the Welfare State. Toronto: University of Toronto Press

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Smith, Heather. “Planning, policy and polarisation in Vancouver's downtown eastside.” Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie.94: 4. 2003: 496-509. Wiley Online Library.

- ↑ Blomely, Nicholas. “Unsettling the City: Urban Land and the Politics of Property.” 2004. Routledge Publishing.

- ↑ Statistics Canada, 2006:http://www12.statcan.ca/census-recensement/2006/dp-pd/prof/92-597/P3.cfm?Lang=E&CTCODE=5296&CACODE=933&PRCODE=59&PC=V6B1G4#Note84

- ↑ http://www.walkscore.com/score/e-hastings-st-and-carrall-st-vancouver-bc-canada

- ↑ Galster, G., "On the Nature of Neighbourhood." Urban Studies. 2001. 12:38. Pages 2111-2124.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Barnes, T. and Hutton. "Situating the New Economy: Contingencies of Regeneration and Dislocation in Vancouver's Inner City" Urban Studies, 2009. 46:5-6. Pages 1247-1269.

- ↑ Warf, B. "Encyclopedia of Human Geography" 2006. Page 649.

- ↑ Bain, Alison. "Re-Imagining, Re-Elevating, and Re-Placing the Urban: The Cultural Transformation of the Inner City in the Twenty-First Century."; Chapter 15 from Canadian Cities in Transition: New Directions in the Twenty-First Century: Fourth Edition

- ↑ Rankin, Katharine. "Commercial Change in Toronto's West-Central Neighbourhoods" 2008. Cities Centre, University of Toronto. Research Paper 214.

- ↑ Shiflet, Kate. "Promoting Equitable Development: Tackling Commercial Gentrification in Historic Districts." 2006. School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation; Department of Historic Preservation. University of Maryland.

- ↑ Howsley, Kelly. "Uncovering the Spatial Patterns of Portland's Gentrification". 2003. Portland State University. 4th International Space Syntax Symposium, London. 76.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 CBC. 2013. "Pidgin owner defends controversial new Vancouver restaurant". http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/story/2013/02/18/bc-pidgin-restaurant-protesters.html

- ↑ The Vancouver Sun. 2013. "Save On Meats hit by vandals; owner suspects anti-gentrification 'anarchists'" http://www.vancouversun.com/life/Save+Meats+vandals+owner+suspects+anti+gentrification/8129222/story.html

- ↑ The Province. 2013. "Downtown Eastside group’s funding will continue despite links to protests" http://www.theprovince.com/news/vancouver/Downtown+Eastside+group+funding+will+continue+despite+links/8230803/story.html)

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Dobson, Cory. "Ideological Constructions of Place: The Conflict Over Vancouver's Downtown East Side". 2004. International Conference for Adequate and Affordable Housing for All; Research, Policy, Practice. Toronto. Pages 1-32.

- ↑ The Province. 2013. "Downtown Eastside groups hit back at anti-gentrification protesters." http://www.theprovince.com/news/vancouver/Downtown+Eastside+group+funding+will+continue+despite+links/8230803/story.html

- ↑ City of Vancouver. 2013. "DTES Local Area Plan Overview". http://vancouver.ca/files/cov/downtown-eastside-local-area-plan-open-house-boards-1-6-07182013.pdf

- ↑ City of Vancouver. 2013. "DTES Local Area Plan Fact sheet". http://vancouver.ca/files/cov/downtown-eastside-local-area-factsheet.pdf

- ↑ City of Vancouver. 2013. "DTES Local Area Plan: Local Economy". http://vancouver.ca/files/cov/downtown-eastside-local-area-plan-open-house-boards-16-17-07182013.pdf

- ↑ City of Vancouver. 2013. "DTES Local Area Plan: Housing in the DTES". http://vancouver.ca/files/cov/downtown-eastside-local-area-plan-open-house-boards-10-13-07182013.pdf

- ↑ City of Vancouver. 2013. "DTES Local Area Plan: Health and Wellbeing". http://vancouver.ca/files/cov/downtown-eastside-local-area-plan-open-house-boards-14-15-07182013.pdf