Course:GEOG350/2013SA/DTES

Introduction

The Downtown Eastside ("DTES") is one of the oldest neighbourhoods in Vancouver and has been an important commercial, residential and industrial centre of Vancouver for many years. The DTES lies on unceded Coast Salish territory and comprises about 202 hectares of land. The DTES includes the sub-areas Strathcona, Gastown, Oppenheimer, Victory Square, and Chinatown and is bordered by Cambie Street to the west, Clark Drive to the east, Venables Street/Prior Avenue to the south, and the waterfront to the north (City of Vancouver, 2012).

The DTES is situated in the heart of the city and has a strong community rich with culture, history and people. Libby Davies, Vancouver’s MP for Vancouver East describes the Downtown Eastside as “a community of people from many backgrounds and experiences who share the place as home in sometimes dire circumstances”(Davies, 2008: 12). There are complex issues that affect the DTES including unemployment, drug use, homelessness, crime, housing issues and a declining economic vitality. Because of these issues it has been targeted for redevelopment since the mid-twentieth century by academics, private developers, civic officials and government. (Plant, 2008)

History

The DTES was developed as a centre of industry, residence and commercial business in the 1880s and 1890s. Hastings Sawmill and the Canadian Pacific Railway yards drew wage workers from all different cultures and backgrounds to work and reside in the DTES. Strong Chinese and Japanese communities developed as a result of immigrant labourers that arrived before the city was incorporated to work in local industries and build the Canadian Railway (Plant, 2008).

After WWII there was a decline in industrial work in the DTES, there was a shift in business westward which continued to drain the Eastside of economic vitality. The social, economic and cultural aspects of the neighbourhood were further impacted by the termination of the BC Electric streetcar service and the North Shore ferries route (Plant, 2008). By the mid-1960s the DTES was getting a reputation for its social and economic and problems, some went as far as to dub the neighbourhood as the “skid road” of Vancouver (Sommers & Blomley, 2002: 30). The postwar reputation of the DTES stimulated numerous redevelopment plans for the area by academics, private developers, civic officials and government alike. In the following centuries, the DTES history is marked by different and reoccurring efforts to redevelop the neighbourhood (Plant, 2008).

The early urban renewal plans started in 1925 as district zoning bylaws that characterized Strathcona as a commercial/light industrial/residential area. Then as social and economic problems persisted, other redevelopment plans advocated for the clearance and complete redevelopment as the only option to counter act what was termed then as urban decay. The majority of the renewal and redevelopment projects resulted in displacement of thousands of people and clearance of whole city blocks (Plant, 2008).

These redevelopment plans were met by opposition of many of the residents, one of the most active groups being the Chinatown residents. In the 1960s there was a mobilization of greater opposition to the city’s redevelopment plans and many community associations were formed to advocate for local resident’s needs and health such as the Strathcona Property Owners and Tenants Association and The Downtown Eastside Residents Association. This forced the government to reassess their approach and focus on improvement of services and socially and culturally sustainable plans rather than demolition and reconstruction projects (City of Vancouver, 2012; Plant, 2008).

Although activism in the area was gaining momentum there were still prominent issues of drug use, crime, prostitution, unemployment, homelessness and intravenous drug-related diseases such as hepatitis and HIV-AIDS. Businesses and investments were pulling out of the area increasing the economic hardships in the neighbourhood. In the 1990s the Vancouver government began to try and address these issues with Four Pillars Coalition which aims to control and reduce drug use. Some of the projects that have come out of this are a needle exchange program, safe injection site and detoxification facility. Other plans include the Strategic Action Plan and creation of the 1999 Downtown Eastside Revitalization program and the 2000 Vancouver Agreement whose objectives are to create healthy safe community with affordable housing, and sustainable economic growth (Plant, 2008). The most current plan is the Downtown Eastside Local Area Plan which “will focus on ways to improve the lives of low-income DTES residents and community members” as a partnership with existing organizations in the area as well as through public engagement (DTESLAP, 2012). Although the more recent redevelopment plans are more inclusive and consider public engagement they remain a contentious issue in the area because of the different interest groups, community organizations and corporations which are trying to fight for representation and control over the region’s future (Plant, 2008).

Demographics

The DTES has a well established Chinatown and a relatively stable population of working class, low-income, and First Nation residents. The neighbourhood is culturally diverse and is comprised of many different local and immigrant communities. The founding immigrant communities include Japanese and Chinese immigrants and labourers as well as other cultural groups such as Scandinavian, British, Italian, Jewish, Ukrainian, and Russian. First Nations also make up a considerable proportion of the DTES; there is a higher percentage of First Nations per capita in the DTES than in the rest of the City of Vancouver. Oppenheimer Park is mainly a Japanese-Canadian community while the edges of False Creek and the intersection of Carrall and Pender Streets comprise Vancouver’s Chinatown. Strathcona and Openheimer are the main residential areas in the DTES (City of Vancouver, 2012).

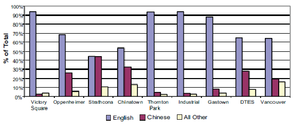

Currently the immigration and the growth rate of DTES are similar to that of the City of Vancouver with about 50/50 immigrant to non-immigrant ratio. The city and the DTES have similar growth rates, with a slight variation between the years 2001-2011, where the DTES had a higher growth rate than that of the city’s. The main language of majority of the residents in the DTES is English and Chinese (Mandarin and Cantonese) is the next most spoken language (Statistics Canada, 2006).

The age profile shows a bias towards an older population with more than half of the population over the age of 45 and with a high percentage of seniors. Males make up the greatest proportion of the gender profile at 60 percent male, and 40 percent female (Statistics Canada, 2006; City of Vancouver, 2012).

Characteristics of the built form and land use

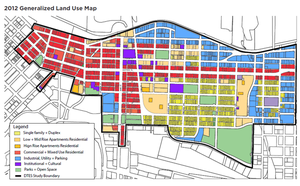

As one of the oldest neighbourhoods in Vancouver the DTES still holds a resemblance of its historic past with approximately 500 buildings in the area listed on the City’s Heritage Register. The built form consists of a mix of commercial, residential and industrial buildings. The residential buildings include market and non-market housing such as apartments, single family and duplex homes, single room occupancy and social housing operated by non-profits or government agencies. The residential areas are mainly in Strathcona and parts of the Oppenheimer District. There are several key commercial/ retail areas such as Water, Hastings, Cordova, Main, Pender and Keefer Streets which are located in Chinatown, Gastown, Victory Square, Thornton Park and parts of the Oppenheimer District. The industry areas are typically to the north and south of the DTES and are of lower density job areas (Statistics Canada, 2006; City of Vancouver, 2012).

There are several parks in the DTES which include Victory Square, Pioneer Place, Oppenheimer and Strathcona but the northeastern portion of the DTES has less access to park or green space than the city’s average (City of Vancouver, 2012).

Transportation infrastructure

Before WWII the DTES had a range of transportation including a streetcar, ferry and steamship which made the area a destination for “warehousing, transportation and commercial activity” (Plant, 2008:4). But after the termination of the BC Electric streetcar service and the North Shore ferries route, transportation infrastructure deteriorated. Now, walkability, pedestrian safety and access to transit have become an issue for many of the DTES residents. Over 65 percent of DTES residents walk, cycle or take public transit to work but access to transportation is difficult for low-income people in the DTES because of fiscal barriers that restrict their ability to travel by public transit or car. There is concern about pedestrian safety and in a study done by Simon Fraser University and the University of British Columbia, it was noted that the DTES is the most dangerous place for pedestrians in Vancouver. This issue is exacerbated because of the large number of vulnerable road users included including seniors, families with children, and people with disabilities, mental illness, and addictions (Statistics Canada, 2006; City of Vancouver, 2012).

What is gentrification?

Gentrification, a term first coined by British Sociologist Ruth Glass, can be described as the process of urban regeneration or change that sees a middle class enter a neighbourhood and displace poorer incumbent residents. Managed gentrification, sometimes call urban renewal of regeneration has been lauded for its ability to improve neighbourhoods by introducing a social mix and reducing the problems stemming from concentrated poverty. The question is has managed gentrification been a benefit or bane to urban development? Some believe that instead of reducing problems, gentrification has created increased disease within inner cities by adding to and accelerating income polarization, displacement, heightened segregation, and class and racial conflict.

Gentrification is difficult to define in academic literature because of its dependance and on localized contexts and urban policies. Furthermore, the ability to measure gentrification is somewhat ambiguous if the goal is to determine if a neighbourhood is better or worse off as a result of urban development. However, a “stages model” is seen as somewhat consistent in many urban centres characterized by the groups moving in and out of neighbourhoods and the investment shaping it. The first stage is often characterized by decay or disinvestment and possibly abandonment primarily because landowners see capital employed in other parts of the economy creating a better return.

New middle class, the gentry, often have strong lobbying powers allowing the emerging population to generate investment for new cultural facilities and infrastructure. These new amenities can further increase land values and are often not suited to the incumbent population. Sometimes the investment into amenities that support middle and upper class residents are viewed as “blatant attempts” to exclude the vulnerable.

Gentrification is attributed to:

- Redevelopment of inner city neighbourhoods with the growth of smaller, non family households.

- The emergence of a new middle class of highly educated, knowledge based sector workers that reject the suburban lifestyle

- deindustrialization that left inner cities with undervalued properties

- Entrepreneurial urban policy: Attracting knowledge based workers with infrastructure and amenity investment

- Increased transportation costs

- Changing demographics: Smaller household sizes but higher price per square foot can help offset the costs of commuting.Possible for two income households with no family.

- Living close to work

Works Cited

City of Vancouver. 2012. Downtown Local Area Profile 2012. Downtown Eastside Local Area Plan. Retrieved from http://vancouver.ca/files/cov/profile-dtes-local-area-2012.pdf

Davies, L. “Forward,” in Hope in Shadow: Stories and Photographs of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, eds. Brad Cran and Gillian Jerome. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2008.

“Downtown Eastside Local Area Plan.” (DTESLAP) vancouver.ca. Last modified August 27, 2012. Retrieved from http://vancouver.ca/home-property-development/dtes-local-area-plan.aspx

Plant, B. 2008. Downtown Eastside Redevelopment Planning.Legislative Library of British Columbia. Retrieved from http://www.llbc.leg.bc.ca/public/pubdocs/bcdocs/450186/200804bp_downtown_eastside.pdf

Sommers, J. & Blomley, N. “‘The Worst Block in Vancouver,’” in Stan Douglas, Every Building on 100 West Hastings. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2002.

Statistics Canada. 2006. Census Tract (CT) Profiles for 0059.3 (CT). 2006 Census. Retrieved from http://www12.statcan.ca/census-recensement/2006/dp-pd/prof/92-597/P3.cfm?Lang=E&CTuid=9330059.03