Course:GEOG350/2012WT1/Gastown

Vancouver Gastown Gentrification

(Prepared by Norman Coulthard, Stephanie Demmers, Winnie Lau)

Introduction

Here we will analyze the processes of gentrification and revitalization in Gastown; who it affects and how it is facilitated.As expressed by David Ley (1) "gentrification is a process involving the movement of people, it involves population displacement which falls unequally among residents and has different costs and benefits to certain groups of people." Often times gentrification occurs through revitalization of older heritage neighbourhoods, as is that case with Gastown. The perseveration of Gastown’s historical heritage has created a rare place in the city of Vancouver, one of history and historical beauty. This has resulted in an increasing attractiveness in this neighbourhood in regards business opportunites through revitalization. Ley (7) defines revitalization as ”a process of change through time which can be measured in different ways, such as changing householder income profile, or changing prices of real estate.” This is exactly the case in Gastown, where a shift in demographics has resulted in higher-class residents displacing lower-class residents. The stakeholders for this issue are the displaced lower-income residents, high-income residents, real-estate development companies, and the City of Vancouver. Because this issue impacts such a wide variety of stakeholders, both socially and economically, this is what makes gentrification and revitalization in Gastown worth analyzing.

Location

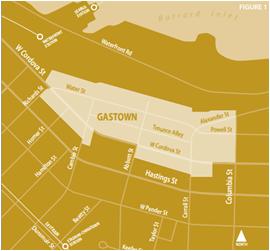

(Source: www.vancouvereconomic.com)

Gastown is a small area located in the North-eastern part of Vancouver Downtown composed of around 8 blocks or 19 acres of land. Its primary boundaries consist of three streets; Water Street, Columbia Street, and Cordova Street. Gastown borders the central business district of Vancouver and the Downtown Eastside.

History

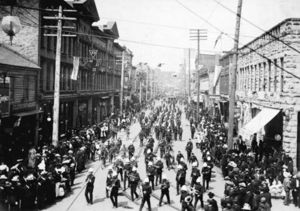

(Source: City of Vancouver Archives 677-533, Photographer: Philip T. Timms)

Late 1800's to Early 1900s

The birth of Gastown began in 1887 with the arrival of the transcontinental railway that brought settlement on the shores of the Burrard Inlet and has uplifted the uses of Industrial, Residential, and Commercial which then established Vancouver as one of the major ports on the Pacific Ocean. The flourishing Burrard Inlet has provided the opportunity for Gastown to become a centre for trade and commerce. It also served as a place of residence for fishermen, loggers, and sailors. The named Gastown came from a man called Jack, Deighton, or ‘Gassy’ who opened up a saloon after a life of seafaring and captaining steamboats. The Great Vancouver Fire, which occurred in 1886, ravaged almost all of Gastown. Many of the architectural heritages that are present today are a collection of the buildings dating from the Great Fire of 1886 to the beginning of the First World War in 1914. ("Wikipedia: Gastown")

1960's and Onwards

From the great depression to the 1960's, Gastown's urban landscape was dramatically transformed. The neighborhood fell into decline and disrepair. Many of the shops were composed of cheap pubs, flophouse hotels, and loggers hiring halls. After Vancouver regained its economic footing in the 1970s, citizens began to raise concerns about protecting the architectural heritage of Gastown since it represented the early beginnings of Vancouver, even going so far as to protest and riot. After the citizen’s hard work of transforming the muncipial culture for conservation, Vancouver have finally recognized Gastown as a national historic site by including on the City's Heritage Register ("Wikipedia: Gastown"). To this day, Gastown and Chinatown has embodied the largest concentration of commercial and industrial heritage sites in the 20th century ("The Gastown Heritage Management Plan" 5).

Demographics

| Gastown | Vancouver | British Columbia | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population in 2001 | 67,269 | 1,986,965 | 3,907,738 |

| Population in 2006 | 79,140 | 2,116,581 | 4,113,487 |

| 2001 to 2006 population change (%) | 15% | 6.5% | 5.3% |

| Private dwellings occupied by usual residents | 79,140 | 817,230 | 1,643,150 |

| Population density (per sq km) | 15,174 | 735.6 | 4.4 |

| Land area (square km) | 0.077 | 2,877.36 | 924,815.43 |

| Total private households | 49, 549 | 817,230 | 1,643,150 |

Population and Dwellings Counts

In 2001, Gastown took up only 3.4% of the total population in Vancouver and 3.7% in 2006. From years 2001 to 2006, there is a minor increase in population at Gastown. This slight increase may be due to the 15% increase in their population from the years 2001 to 2006 (2001 at 67,269 and 2006 at 79,140). Gastown is a highly densely populated neighbourhood averaging at 15,174 per sq km in comparison to the less dense Vancouver area which is at 735.6 per sq km. (Statistics Canada). The population density is so high can be explained by the high distribution of private dwellings. Gastown took up 9.7% of private dwellings in Vancouver. Within this small stretch of land, Gastown took up almost 10% of private dwellings of Vancouver. (Statistics Canada)

Gastown’s Housing

The average apartment/condo price at Gastown is $427,600 which is slightly lower than Vancouver’s average housing price (which is around $480,400). The average household income at Gastown is around $64,500 (2008). This is relatively low in comparison to Vancouver which averages at $75,800. The lower than average income level at Gastown might also explain why there is an above-average population of renters. While Vancouver has an average 53% of renters, Gastown has reached a shocking 69%. ("Gastown: Neighbourhood Profile" 1)

| Gastown | Vancouver | Metro Vancouver | |

|---|---|---|---|

| English | 79% | 65% | 71% |

| Chinese | 28% | 62% | 47% |

| Korean | 15% | 3% | 7% |

| Persian(Farsi) | 11% | - | 4% |

| Japanese | 10% | - | - |

| Spanish | 7% | - | - |

| Punjabi | - | 6% | 16% |

| Tagalog (Filipino) | - | 6% | 5% |

| Vietnamese | - | 4% | - |

Languages at Gastown

There is a higher than the Vancouver average of those who speak English at Gastown. Ironically, the same proportion of those who speak Chinese as their first language only took up 28% of the population at Gastown. Surprisingly, Korean took up a higher than average number with 15% at Gastown in comparison to the small 3% in Vancouver. ("Gastown: Neighbourhood Profile" 2)

Transportation Infrastructure

Methods of Travel to and From Gastown

Gastown's two commercial streets; Cordova and Water are major transportation routes for commuters and traffic volumes can peak as low as 22,000 to as a high as 25,000 cars per day. ("Gastown: Commercial Profile" 5). Because of the high traffic volumes within Gastown, residents of Gastown tend to prefer commute through public transportation or walk. Since Gastown is situated in the North-eastern part of Vancouver Downtown, it is credible to see that they are very well connected in terms of public transportation. Indeed, Gastown is adjacent to one of the busiest Transit Stations in Vancouver – The WaterFront Station. It is very convenient to travel to and from Gastown since the Waterfront Station is only 5 minutes of a walking distance.

The Waterfront Station (formally known the CPR terminal building) serves as a major transportation hub for more than 35,000 passengers for their daily commute through SeaBus, SkyTrain, as well as West Coast Express. ("Gastown: Commercial Profile" 5). The SeaBus is a passenger-only ferry that crosses the Burrard Inlet and connects Downtown Vancouver to the North Shore. (Translink). The SkyTrain is a rapid-transit train that is fully-automated and driverless system. There are two main SkyTrain Lines; Expo and Millennium Line and Canada Line.The Expo and Millennium Line connects Downtown Vancouver to the cities of Burnaby, New Westminster, as well as Surry. The Canada Line connects Downtown Vancouver to the Vancouver International Airport (YVR) and the city of Richmond. The two SkyTrain Lines serves on average of around 250,000 passengers every week. (Translink). The West Coast Express is a railway service for those travelling to and from Downtown Vancouver to the City of Mission. This TrainBus has provided service for an average of 11,000 passengers every week – totaling of around 2.8 million passengers per year. (Translink). On top of that, the Waterfront Station provides several bus routes as well as providing access to the Helijet terminal that takes passengers to and from Vancouver Island every day. ("Gastown: Commercial Profile" 5).

Methods of Travel in Gastown

Since the two commercial streets are very busy, most people prefer to walk in Gastown. Pedestrian counts have shown an average of 66 to 183 pedestrian counts at the North-South blocks and 190 and 1,027 people at the East-west blocks. According to Statistics, the North side of Gastown is the busiest and has been ranked Vancouver’s 38th busiest. ("Gastown: Commercial Profile" 5).

Characteristics of the Built Form and Famous Landmarks

Gastown is a unique neighborhood within the City of Vancouver because it does not share the same modern characteristics that have come to define much of Vancouver. Many of the buildings at Gastown have preserved historic building styles of the Victorian Italianate and Edwardian era. Today, it is unfortunate that only 28% of these buildings reflect the pre-1946 standards as most of them have been refurbished. ("The Gastown Heritage Management Plan" 5). Even though all the buildings at Gastown have a historical characteristic, this is not the case. Buildings that were constructed after the 1950s have mirrored Gastown's historical glamour. Unlike most downtown areas where majority of the buildings have been built post-1980s, only 6% of Gastown's buildings were built post-1990s. ("Gastown: Commercial Profile" 2).

Characteristics of the Built Form

The perseveration of its historical heritage has reflected the historical development of Gastown. The historical architecture of the area varies both width and height. For example, some buildings have a height of 13 stories while others only have 1 or 2 stories. The variation in height creates a “sawtooth” appearance from a bird’s-eye-view. This “sawtooth” appearance is more prevalent in Water Street. This profile has reflected the needs and aspirations of original owners as well as the time these structured were constructed. The collection of buildings’ appearance in Gastown varies in character with large floor plate warehouse buildings along Water Street and narrow and elaborate buildings along Cordova Street.("The Gastown Heritage Management Plan" 7).

Architectural Compositions and Use of Materials

Even though these buildings vary in architectural character, there is a strong similarity in their architectural compositions as well as use of materials. The three most common materials used are masonry: sandstone, granite and brick.("The Gastown Heritage Management Plan" 7).

Famous Landmarks

Every year, approximately 9 million tourists from around the world come to Vancouver. Gastown is a must-see destination for many visitors because of the many famous landmarks such as the Steamclock and ‘Gassy Jack’ Statue just to name a few. ("Gastown: Commercial Profile" 5) ("An Introduction to Gastown"). In honor of 'Gassy Jack', City of Vancouver has paid respect for man who was the inspiration behind the name Gastown by erecting a statue of him. The Steamclock, on the other hand, is a steam powered clock that is represents this North-eastern space of Vancouver Downtown. The most unique feature of the clock is that it blows out steam and plays the Westminister Chimes every hour. It was originally designed in 1875 but it was not until 1977 that the steamclock was created. ("An Introduction to Gastown"). Other landmarks worth touring are the many plaques in front of the historic buildings. These plaques are symbolic in which it lets the visitors learn about Gastown's history.("Gastown: Commercial Profile" 5).

Demographic Analysis

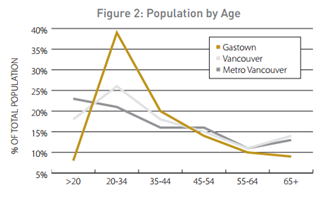

(Source: www.vancouvereconomic.com)

Although the processes of gentrification can be very different from one another, Gastown shows trends of classic gentrification in its demographics, and as a result it has undergone revitalization. Classic gentrification is form of gentrification which is marked by the immediate displacement of lower-class residents and replacement with higher-class ones (Ley 7). The initial residents are of lower socioeconomic status and they become forced out by wealthier middle-class "pioneers" (133). The pioneers are trendy, "creative class" residents that create desire for other middle and upper class residents to move into the area later (Kerstein 622). Revitalization is how classic gentrification manifests itself. This is when the socioeconomic status of residents changes or prices in the housing market begin to rise, without necessarily physically redeveloping the area (Ley 7).

As seen in the Demographics section, the residents of Gastown are primarily English speakers of Caucasian descent, and just under half of them hold university degrees. This is typical of neighbourhoods that have experienced classic gentrification and revitalization (Ley 116). The age-range of the residents of Gastown consists of about 39% between the ages of 20 to 34 as well. The age and education trends are very similar to Robert Kerstein's report on the stage-model changes in South Hyde Park, Tampa (Kerstein 627). Despite the average-income in Gastown seeming to be on the low-end, the cost of real-estate is well above the average price than all of Metro Vancouver. Compared to an established suburb of the city such as West Vancouver, however, it is not as expensive to buy real-estate.

It is difficult to typify all of the processes that have taken place in Gastown. Revitalization is dominant because of the primarily young, well-educated caucasian residents (Ley 8). It has also experienced decline and redevelopment, as buildings such as Woodwards have fallen into disrepair only to be redeveloped into an upscale urban landscape complete with new residential and commercial tenants. The culture has been defined by the night-life, such as bars and restaurants, people have been displaced, and trends of gentrification have been noticed by scholars and media. Prices are now climbing for real-estate, and large-scale developers are setting their sights on using land in Gastown.

Why Analyze Gentrification in Gastown?

The issue of gentrification in Gastown has multiple stakeholders. One stakeholder group is the displaced lower-income residents who are pushed further east and to neighbourhoods that do not provide the same standard of living, whether it is food quality and availability, accessibility and relative distances, or simply put: general well-being.

Another stakeholder group are high-income residents who are looking interesting housing and higher-order consumption experiences. These residents generally do not want to live in close proximity to low-income social housing or other related buildings, primarily because of fear of crime as well as economic interest. Both low and high-income citizens have just as much of a right to own a house as one another, but the tendency is for high-income residents to displace low-income residents. They further change the neighbourhood by demanding a sense of safety that quite often goes along with gentrification. This is where various methods, such as gated communities, security cameras, and security guards are used to ensure (or at least give a sense of) less crime in the area.

Another major factor for influencing the residential decisions of high-income residents is that having social housing is thought to be harmful towards property value, although this is not truly the case (Nguyen 16). These residents fear that their property will lose value as a result of several outcomes of affordable housing development. Their major focus is on the quality and aesthetic view of housing and nearby structures, as well as a perceived decline in the overall community and neighbourhood ultimately playing out into the real-estate market (Nguyen 16).

Another stakeholder group are the real-estate development companies. These players often look to turn a profit from rezoning an area. These companies are required here to set aside at least 20% of the land for low-income purposes (CHMC). This does not dictate exactly what they do with the land though, and they tend to leave it open to the city for things like urban gardens, or instead of rebuilding they renovate.

Finally, the last stakeholder group is the City of Vancouver. The City seeks to provide housing for lower-income residents, especially since Vancouver has such steep real-estate costs. At the same time they work to satisfy the high-income residents who have ‘political clout’. They have attempted this by requiring real-estate development to set aside 20% of the land for low-income purposes, but they still must provide the money in order to develop social housing. This development plan is good for crime reduction without heavy securitization, but it is hard to actually sell the units. More common to Gastown, landholders, promoted by the City, have renovated their old buildings to give Gastown an historic feeling. The result: the oldest neighbourhood in Vancouver becomes beautifully revitalized. As a result, it is a more attractive place for trendy, creative, and high-income residents.

The gentrification of Gastown is worth analyzing because it is an issue that all of the stakeholders are involved in monetarily. It also affects the well-being of various economic groups of residents. It can also show us the outcome of mixed-income development, of which the results are currently unclear. Gentrification is also related to homelessness and crime which are two separate issues that are important in Vancouver. Vancouver is also increasingly being used as a model for urban development, and gentrification is a trend that occurs globally manifesting differently in each city. Knowledge from the gentrification of Gastown could be applied globally to issues in other cities.

The causes behind the gentrification of Gastown were originally the group of pioneer-type cultural classes moving in, but now it is more the high-rise development groups who have run out of room downtown and are starting to move towards the east-side.(Paulsen, a5). This is combined with the economic weakness of the city in not funding social housing development through being more rigorous on mixed-income development policy, which is fairly relaxed (CMHC). Some other underlying causes would be the upper-class desiring a certain aesthetic or community with their neighbourhood, so they move into a ‘trendy’ area such as Gastown.

Low-income Displacement

Gastown’s vibrant and lively day and night scene coupled with its beautiful historic façades make it a trendy place to live and for tourists to visit. Resultantly, many individuals lack the ability to keep up with Gastown’s socio-economic growth, and due to increased rent and cost of living these people have been displaced from the neighbourhood. A resulting issue for these low-income residents is that many find themselves in different neighbourhoods which offer lower standards of living. Although there are measures for gentrification in some American cities, it is fragmented in Canadian cities and has proven difficult to assess in number (Ley 145).

Being continually pushed eastwards residents are exposed to pollutants that get swept into the Fraser Valley by the winds funneling in from the ocean. This can lead to health problems which may not necessarily have occurred had they been living in an area with better air quality (Li 5719). Also, certain areas of Vancouver are more at risk of flood and damage from earthquake, and the risk generally increases the further east one goes (Clague 20).

Also, despite not having any clear indication in Vancouver, low-income residents from gentrified areas around North America have been subjected to “food deserts,” where they cannot access food that is affordable enough while still maintaining decent nutrition (Mead a335). This can happen when they still live in the area being gentrified as the grocery stores become replaced by more expensive ones and the cost of eating at restaurants increases. It can also happen after having relocated to a new area, where there may be a lack of grocery services. As a result people can end up eating food purchased from corner stores or fast food instead of a more healthy choice. This can lead to health problems later in life (a335). As the area becomes more gentrified, the cost of other services will rise as well. This is a result of the new demands of the gentrifiers and it can manifest in areas such as the retail sector (Ley 192. The increase in price that goes along with this can drive more low-income residents into displacement, as they cannot afford to buy anything in the area that they live in. These citizens may also ultimately end up jobless from not being able to make the commute to their previous jobs.

Government Influence

Cory Dobson, says “the role of public policy, neighborhood political mobilisation and various combinations of population and land use characteristics…are normally unattractive to gentrifiers.” Essentially, increased role of government ascertains an area which is influenced by regulation and may not be easily gentrified. Dobson indicates that even though municipal government may look to create subsidies in areas, this “will commonly require the joint will of the local state and senior level government” in order to be a fiscal success. Often time’s political mobilisation will attempt to draw attention towards to potential harmful effects of gentrification, and the resulting displacement of a poorer demographic. (Dobson 2008, 2475) The ability for the government to mitigate the negative impact of gentrification has lessened in recent decades, combined with the anti-gentrification tactic of renovation versus new builds in lower income neighbourhoods (Gastown) has resulted in beautiful housing just outside the downtown core. Gastown is “adjacent to long-existing higher-status districts” such as the downtown core, this makes at an attractive neighbourhood for the local professionals, not only due to accessibility but because the area has been heavily rejuvenated. Unlike the bit further Downtown Eastside, Gastown has not been able to avoid heavy gentrification largely due to the Woodward’s project intent for revitalization. The government has pushed for the regeneration of Vancouver’s oldest neighbourhood. Consequentially, Gastown has become a skillfully revitalized area where land values have increased due the attractiveness of this neighbourhood for trendy, creative, high-income Vancouverites.

Mixed-income Development and Urban Regeneration

This idea was really picked up in Vancouver with requirements that 20% of land-use in real-estate development must have low-income stakeholders in mind. However, this does not mean social housing, and developers quite often do not build social housing because they are looking to turn more of a profit and low-income housing can be harmful to property value. Urban gardens often show up in these areas instead, which is not inherently bad, with the added green-space and water run-off capacity, but it is still displacing low-income residents from potentially available housing space. Though urban gardens are not common to Gastown, mixed-income development in Gastown is evident in the Woodwards building: a big department store that after a decline a project (of which SFU is currently a public partner to) for regeneration and social housing was implemented.

The City of Vancouver has encouraged building owners to renovate many other historic buildings instead of rebuilding; often termed as urban regeneration. Maloutas (2011, 1) argues that “gentrification becomes quasi synonymous with urban regeneration”; this supports the increasing association of areas of urban regeneration and the resulting increased socio-economic status of the new residents. Policy makers and investors involved in urban regeneration projects tend to avoid the topic of gentrification because its association “denotes processes of urban regeneration and underlines the advantages for capital investment versus the bleak fate of displaced residents from renovated areas.” (Maloutas 2011, 1) In other words, in an attempt for capital gain, often times gentrification as a concept tends to be ignored in areas of urban regeneration due to it’s negative connotation with low-income displacement and unaffordable housing. Instead, attention is funneled towards ideas of an invigorated neighbourhood which makes Vancouver a more beautiful and attractive place to live.

This idea of “urban regeneration” has largely influenced the gentrification of Gastown and has created an historic neighbourhood which borders Vancouver’s financial and business districts; making it a desirable location for higher income residents and essentially unaffordable location for lower income residents. This resultant displacement is a large negative impact of gentrification, especially in a city where land values are exorbitant and affordable housing is in dire need. The weight that this displacement bears on housing for much of Vancouver’s lower income residents seemingly outweighs the financial and social gains.

Conclusion

It is evident that gentrification has taken place in Gastown, primarily through its demographics. A large proportion of Gastown’s residents that display trends of classic gentrification, which consist of fairly young, primarily English-speaking educated people of Caucasian descent. These demographics are a result of revitalization which has occurred. These trends are important to consider because of Gastown’s historic central location in the heart of Vancouver, and because of the various groups of people who are involved with it. The historic aspect and trendiness of Gastown make it appealing for high-income residents, as well as urban regeneration. Urban regeneration has taken place in Gastown and has made it more desirable for gentrifiers. Agencies such as the municipal government and development groups can help influence regeneration as well. Ultimately low-income residents are negatively impacted, and they can be subject to income and health issues afterwards.

Sources

1. "An Introduction to Gastown." About.com Vancouver Travel. The New York Times Company, n.d. Web. 25 Oct. 2012. <http://govancouver.about.com/od/vancouverneighborhoods/a/Gastown.htm>

2. Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. "Using Inclusionary Policies." http://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/en/inpr/afhoce/tore/afhoid/pore/usinhopo/usinhopo_006.cfm

3. "Census Tract". Statistics Canada. Statistics Canada: The National Statistical Agency, n.d. Web. 25 Oct. 2012 <http://www12.statcan.ca/census-recensement/2006/ref/dict/geo013-eng.cfm>

4. Clague, J. John. "The Earthquake Threat in Southwestern British Columbia: A Geologic Perspective." Natural Hazards. 2002, Volume 26, page. 7–34. http://download.springer.com/static/pdf/291/art%253A10.1023%252FA%253A1015208408485.pdf?auth66=1350694070_fb96111144f46931db6dac2f8fad24e4&ext=.pdf

5. Dobson, C., & Ley, D. (2008). "Are there limits to gentrification? the contexts of impeded gentrification in vancouver." Urban Stud, 45(2471), doi: 10.1177/0042098008097103. http://usj.sagepub.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/content/45/12/2471.full.pdf+html

6. Kerstein, Robert. "Stage Models of Gentrification: 'An Examination.'" Urban Affairs Quarterly. 1990, Volume 25, Issue 4, page. 620-638. http://uar.sagepub.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/content/25/4/620.full.pdf+html.

7. Ley, David. "Gentrification in Canadian Inner Cities: Patterns, Analysis, Impacts, and Policy." Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation - External Research Grant. 1985.

8. Li, Shao-Meng. "A concerted effort to understand the ambient particulate matter in the Lower Fraser Valley: the Pacific 2001 Air Quality Study." Atmospheric Environment. 2004, Volume 38, Issue 34, page. 5719-5731. http://www.sciencedirect.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/science/article/pii/S1352231004005874

9. Gastown: Neighborhood Profile. Bizmap: Market Area Profiles, 2009. Web. 25 Oct. 2012 <http://www.vancouvereconomic.com/userfiles/gastown-neighbourhood.pdf>

10. Gastown: Commercial Profile. Bizmap: Market Area Profiles, 2011. Web. 25 Oct. 2012 <http://www.vancouvereconomic.com/userfiles/gastown-commercial.pdf>

11. "Gastown". Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc.,n.d. Web. 25 Oct. 2012 <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gastown>

12. The Gastown Heritage Management Plan. City of Vancouver, Planning Department, Heritage Branch, 2001. Web. 25 Oct. 2012 <http://vancouver.ca/files/cov/gastown-heritage-management-plan-2001.pdf>

13. Maloutas, T. (2012). "Contextual diversity in gentrification research." Critical Sociology, 38(1), 33-48. doi: 1 0.1177/0896920510380950 http://crs.sagepub.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/content/38/1/33

14. Mead, M. Nathaniel. "The sprawl of food deserts." Journal: Environmental Health Perspectives. 2008, Volume 116, Issue 8, page. a335. http://web.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=fb671343-9c99-47f2-a5f8-9406d4373715%40sessionmgr14&vid=2&hid=13

15. Nguyen, M. Thi. "Does affordable housing detrimentally affect property values? A review of the literature." Journal of Planning Literature. 2005, Volume 20, Issue 1, page. 15-26. http://jpl.sagepub.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/content/20/1/15.full.pdf+html

16. Paulsen, Monte. "B.C. developer sets sights on Downtown Eastside; The purchase of a half-block of properties in Canada's poorest urban area could lead to further strain on the city's homeless, critics say." National News. 2007, page a5. http://www.lexisnexis.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/lnacui2api/results/docview/docview.do?docLi nkInd=true&risb=21_T15829519060&format=GNBFI&sort=BOOLEAN&startDocNo=1&resultsUrl Key=29_T15829519052&cisb=22_T15829519062&treeMax=true&treeWidth=0&csi=303830&do cNo=9

17. "SeaBus Schedule". Translink. Translink., n.d. Web. 25 Oct. 2012 <http://tripplanning.translink.ca/hiwire?.a=iScheduleLookupSearch&LineName=998&LineAbbr=998>

18. "SkyTrain". Translink. Translink., n.d. Web. 25 Oct. 2012 <http://www.translink.ca/en/About-Us/Corporate-Overview/Operating-Companies/SkyTrain.aspx>

19. "WestCoast Express". Translink. Translink., n.d. Web. 25 Oct. 2012 <http://www.translink.ca/en/About-Us/Corporate-Overview/Operating-Companies/WCE.aspx>