Course:GEOG350/2012WT1/False Creek

Urban Transformation of False Creek

Gentrification and Negative Impacts of Industrial Removal in Southeast False Creek, Vancouver

(prepared by V. Janickova, D. Sharp, W. Hamberlin )

Introduction

What Is Gentrification?

Gentrification is a difficult term to define as it is “chaotic” and refers to many diverse redevelopment processes that result in unique inner city developments (Mills 14). It was originally coined by sociologist Ruth Glass in the 1960s, but has since transformed to take on many different and more complex meanings. It is a term that highlights the economic, cultural, social and physical aspects of inner city change. According to Caroline Mills’ thesis, the term has been used to refer to the revitalization process of urban change, “but underlines the class character of this process” (Mills 2). Classic models and studies of gentrification highlight the social and physical changes that result from this process (Mills 3).

From a social standpoint, gentrification involves middle class individuals replacing working class individuals and families in deteriorating inner city neighbourhoods. Mills refers to this as “population turnover” (Mills 4). According to Mills, these gentrifiers that were conventionally described as being young, single or married without children, may actually be an extremely diverse group of individuals. In fact, studies indicate that over 60% of gentrifiers of the Grandview-Woodland area of Vancouver actually had children (Mills 5).

Urban gentrification is associated with migration within a population. This generally results in the displacement of the poorer, pre-gentrification residents, who are unable to pay increased rents or housing prices and property taxes. Often old industrial buildings are converted to residences and shops. In addition, new businesses, catering to a more affluent base of consumers and those that can afford increased commercial rent, move in, further increasing the appeal to more affluent migrants and decreasing the accessibility to the poor.

Traditionally, gentrification is the “movement of capital investment into the inner city built environment” through various redevelopment projects (Mills 10). The revitalization efforts of gentrifiers profoundly effects the economic, cultural, social and built environments of gentrified inner city neighbourhoods, resulting in both positive and negative aspects of these changes. This article will focus on the negative externalities of gentrification in False Creek, Vancouver.

Why are Deindustrialization and Gentrification Worth Analyzing?

The re-development of False Creek with regards to gentrification and industrial removal in the community is particularly important because it is contrary to the original intentions of the municipal government's planning vision.

In our study, we aim to demonstrate that deindustrialization in False Creek has led to a permanent shift away from industrial production as a key sector of Vancouver's local economy. The subsequent gentrification of this neighbourhood has displaced many working class families and individuals, while creating an influx of housing designed specifically for middle to high income earners. This redevelopment project has further spatially polarized Vancouverites by encouraging (typically white) middle income earners and higher to occupy inner city neighbourhoods while marginalizing low income ethnic minorities to suburbs far from the downtown core.

Gentrification causes a loss of industrial land, which results in municipalities having to implement extra measures to protect industrial land. An example of these extra measures is the fact that the City of Vancouver adapted new measures that forbids rezoning of industrial land as it is in the case of South Vancouver Industrial Area. (City of Vancouver Policy Report Urban Structure UB-1). Moreover, to protect the industrial land, the City of Vancouver could incorporate light industrial zones into redevloped neighbourhoods.

Southeast False Creek lost manufacturing jobs directly as a result of deindustrialization. As such, the service sector was unable to absorb the sudden increase in the supply of labor, causing higher unemployment and driving lower income groups out of the community. Between 1966 and 1980, the number of businesses and professional service firms increased by over 140% while little concern was paid to the dislocation effects on the city’s industrial base a whole (Stiftel et al. 36).

Although, False Creek was originally planned to be re-developed in a manner that championed diversity among income classes, emphasized environmental values and provided affordable public housing for low-income groups, this plan has "unofficially" failed. (Stiftel et al. 32).

Moving forward, policymakers and city planners need to properly articulate their values with regards to low-income housing to combat the polarization that has occurred in Vancouver. Furthermore, Vancouver city officials need to adopt strict exclusionary and inclusionary zoning policies that encourage developers to building more affordable housing units, and leave the few industrial production centers that still exist intact. The loss of jobs in the industrial sector and the decline in low-income housing in the inner city has subsequently resulted in the marginalization of low-income groups. Extraordinary housing prices, and underemployment and unemployment have shifted these groups to the Downtown Eastside or even out of Vancouver. Issues such as homelessness, unemployment and the lack of housing for individuals employed in the service sector are important problems that need to be tackled. Thus, the impacts of gentrification and deindustrialization in False Creek are worth analyzing.

False Creek and Gentrification

False Creek, like many other waterfront neighborhoods across North America, has undergone a process of de-industrialization over the past several decades. Municipal policies have allowed the removal of industrial sites and low to middle-income housing. Old houses have been demolished and replaced with modern, yet unaffordable, condos. As such, lower income residents formerly living in the area have been forced to move and now live further away in the suburbs. According to Alison Bain in chapter 15 of Canadian Cities in Transition, “intensification in the form of high-rise condominium towers that commonly cater to childless singles or couples from the middle and upper classes who seek maintenance-free living has created vertical gated communities…creating islands of wealth and privilege where residents may seldom interact with each other or with the people and spaces of the surrounding neighbourhood” (Bain 267). Consequently, the redevelopment of False Creek has promoted social and cultural homogeneity of the neighbourhood, while encouraging polarization of the richest and poorest Vancouverites.

Deindustralization of Southeast False Creek

Since the 1960's the employment levels in the manufacturing sector have fallen dramatically in False Creek; this decline is a phenomenon widely referred to as deindustrialization. Deindustrialization has caused considerable concern with regards to the local economy and has given rise to a debate about its causes and likely implications. Bain states that “since the 1970s and accelerating after expo 86 and into the 2010 winter Olympics, Vancouver has strategically transformed its waterfront from industrial and railway use to residential and recreational use” (Bain 268). As such, critics regard deindustrialization with alarm and suspect it has contributed to widening income inequality. Some suggest that deindustrialization is a result of the globalization of markets and has been fostered by the rapid growth of North-South trade (trade between the advanced economies and the developing world). These critics argue that the fast growth of labor-intensive manufacturing industries in the developing world is displacing the jobs of workers in the advanced economies (Rowthorn, Robert, and Ramaswamy 1). Deindustrialization is especially problematic because it could lead to structural unemployment, in that many Vancouverites are out of work because the jobs that they were trained to do no longer exist.

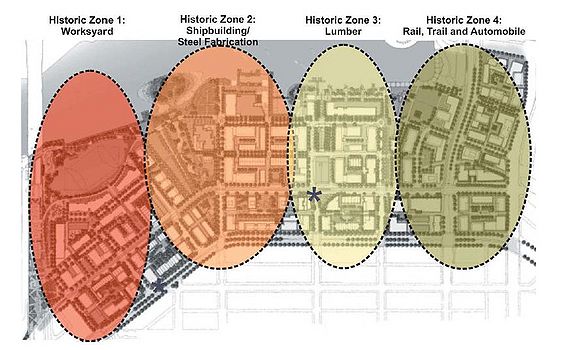

SEFC's Industrial Historic Zones in early 1900s to 1960s:

(Commonwealth BUFO Incorporated Interpretive Strategy Southeast False Creek)

Versus

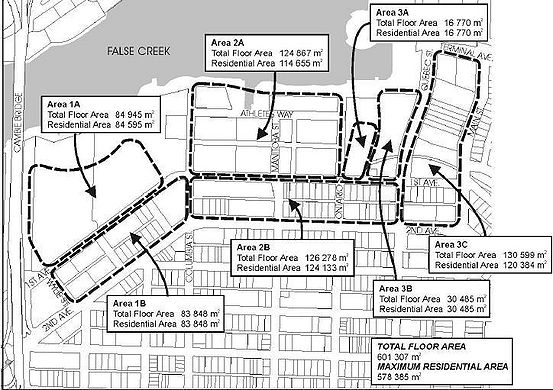

2007's Proposed Total Floor Area and Residential Floor Area in SEFC:

(City of Vancouver Southeast False Creek Development Plan)

The Neighbourhood Analysis

Location

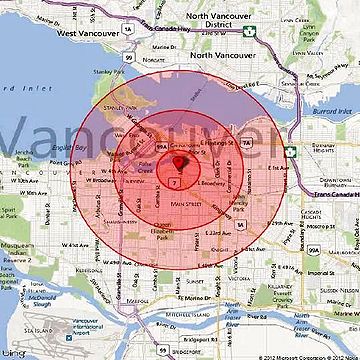

False Creek is a short inlet in the heart of Vancouver, separating downtown from the rest of the city. Science World is located at its eastern end and the Burrard Street Bridge crosses its western end. False Creek is also spanned between the Granville Street and Cambie bridges. The Canada Line tunnel crosses underneath False Creek just west of the Cambie Bridge. It is one of the four major bodies of water bordering Vancouver along with English Bay, Burrard Inlet and the Fraser River (False Creek Homes and Location).

Southeast False Creek is an area of former industrial land situated on Vancouver’s False Creek waterfront. The site is approximately 36 hectares comprising both publicly and privately owned land (City of Vancouver Southeast False Creek Location).

History

The history of False Creek is intimately tied to the history of Vancouver. The area was originally inhabited by aboriginal people for thousands years. In 1859 a British surveyor, George Henry Richards, discovered that a centuries-old fishing settlement that he was interested in, did not connect to Vancouver's inner harbour. He was so disappointed with his discovery that he dismissed the area as a "false creek". Today it is lined with wonderful restaurants and waterfront condominiums on the downtown and Yaletown side, and the fabulous markets, marinas and shops of Granville Island on the other (False Creek History).

According to the City of Vancouver website, Southeast False Creek has been an industrial area since the late 1800s. Its industrial uses have included sawmills, foundries, shipbuilding, metalworking, salt distribution, warehousing, and the city’s public works yard. During the early 1900s, False Creek became lined with sawmills and shingle mills employing 10,000 workers, and Mount Pleasant filled with houses to 1st Avenue. The Industrial Age peaked in Vancouver’s False Creek during the war years - as about 5,000 workers laboured at the Canron site, and thousands of others were employed in sawmills, smaller machine shops, foundries and manufacturers of industrial equipment.

In the 1960s industry began to leave False Creek and would not be replaced. In 1970 city council decided to rezone much of False Creek for housing and parks -- the shoreline was transformed into a vibrant community edged by a waterfront seawall, dotted with green spaces and housing in the forms of condominiums, co-operatives, floating homes and low-income apartments. In the 1980s Expo 86 became the sole reason to clear all industry from the north shore of False Creek. Following Expo, the Province sold the North False Creek (NFC) site to Li Ka-shing, who brought ideas of a higher density waterfront community to the downtown peninsula. The 1991 Official Development Plan enabled significant new density commensurate with the provision of significant public amenities including streetfront shops and services, parks, school sites, community centres, daycares, co-op and low-income housing. Since then, most of the north shore has become a new neighbourhood of dense housing (about 100 units/acre), adding some 50,000 new residents to Vancouver's downtown peninsula. The industries of Southeast False Creek held on till 1990, when Canron moved out of the Canron Building. This huge historic building was torn down in 1998 (City of Vancouver Southeast False Creek History).

A new addition on the southeast bank is ‘The Village’ in False Creek. It was built as the athletes' village for the 2010 Winter Olympics, so it is also referred to as the ‘Olympic Village’.

The City of Vancouver has plans to see this neighbourhood developed into a residential area with housing and services for 11,000-13,000 people. By 2020, Southeast False Creek will be home to 12,000-16,000 people and will have six million square feet of development (City of Vancouver Southeast False Creek History).

Demography

Southeast False Creek (SEFC) has its own unique and diverse population; however, as a result of deindustrialization and gentrification of the area, as well as increased influx of immigrants, the population mix has changed rapidly over past 30 years.

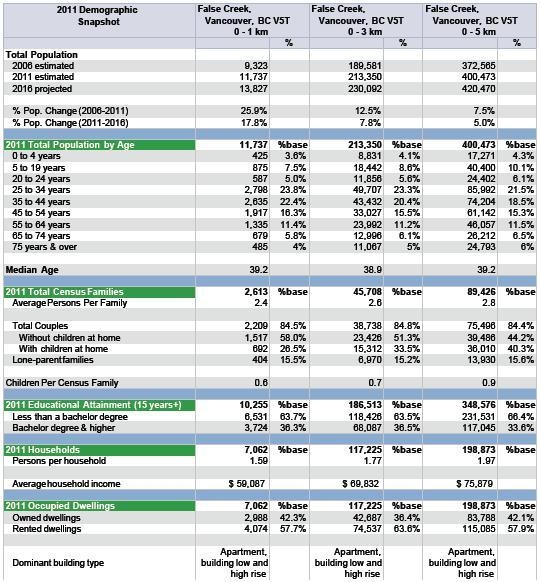

According to Tetrad's on line census and BC Statistics data, in 2011 the total population in the SEFC neighbourhood was 11,740 people, which is a 25.9% increase from 2006 year. It is estimated that by the year 2016, the population will grow by 17.8% to 13,827.

The residents are primarily Caucasian descendants and Asians. Since the 1980s immigration in the region has dramatically increased, making the region more ethnically and linguistically diverse. There are three major visible minorities in False Creek: Chinese, Korean and West or South Asian. The official home language is English and the major non-official home language is Cantonese.

In terms of age mix, there is a considerably large number of middle-age individuals living in the region – 62.5% of population is between years of 25 to 54. Most of the residents are highly educated, creative class professionals with university degrees.

In 2011 the average annual household income in the SEFC was approximately $62,000, and 2016 projection shows average annual household income growing to approximately $80,000. This change is also a sign of gentrification process in the area as people with higher incomes are moving into False Creek, pushing the lower income group away to other neighbourhoods.

In terms of households, in 2011 there were 7,062 homes in SEFC. This number is also projected to increase by 13.5% by 2016.

According to BC Statistics, False Creek's residents are employed in the following sectors:

• Management - 22% of total employment

• Business finance and administration - 20% of total employment

• Sales & Services - 16% of total employment

• Health & Science - 14% of total employment

• Public Service - 10% of total employment

• Arts & Culture & Recreation - 10% of total employment

• Others (trades, manufacturing and utilities, etc.)- 6% of total employment

• Industrial & Manufacturing - 2% of total employment

2011 Demographic Snapshot - Southeast False Creek:

(Tetrad Southeast False Creek Demography)

Transportation Infrastructure

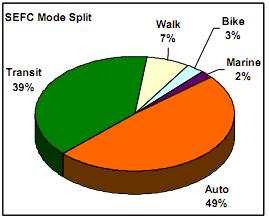

Planners developed a hierarchy of users for streets and transport. Starting from highest priority to lowest priority, streets were designed first for pedestrians, bicyclists, public transit, service vehicles, and lastly, cars. Streets, themselves, have a hierarchy as well, based on uses, with minimum emphasis on arterial, through streets. Streets were designed with the pedestrian and non-motorized traveller in mind (False Creek Transportation- Green Urbanism and Ecological Strategy Southeast False Creek).

The transportation infrastructure of False Creek is connected to the Cambie Street Bridge, Main Street, and Second Avenue, which all link to the down town core and Central Broadway. This accessibility and close proximity allows for large traffic flows by vehicular and non-vehicular commuters. As stated in the "Southeast False Creek Transportation Study" on Transport Canada Government Website, an estimated 50% of trips to and from False Creek are made by auto, with the rest made by public transit, walking, and bicycles, as shown in the mode-split chart.

There are several bicycle safe routes on Ontario, Seaside, Off-Broadway, and Adanac. False Creek is also situated close to the Olympic Village Sky Train station, street car lines, a number of ferries, aqua buses, and a Greyhound bus station. Residents can also choose to use community transit passes and car-sharing services like Zipcar that are located in numerous locations around the neighbourhood (Southeast False Creek Transportation Study).

Underlying Causes of Gentrification in Southeast False Creek

Influx of the “Creative Class”, Housing Shortage and Scramble for Waterfront Property

The relocation of many head offices of large companies to Vancouver as well as the proliferation of the film industry and other artistic projects has led to an influx of people, belonging to Richard Florida’s “Creative Class” or knowledge-based class, looking for housing in interesting or stimulating neighbourhoods in Vancouver. This demand for housing has driven up the cost of real estate within these “desirable” areas. Florida argues that “the question of where” is one of the most important questions people have to answer, as the place people choose to live in directly effects every other aspect of life (Florida 6). Andrejs Skaburskis and Markus Moos in "The Economics of Urban Land" offer that “people may be willing to pay more for locations close to parks, views and quiet surroundings” (Skaburskis and Moos 227). Essentially, because there is such great demand for waterfront properties private developers are able to charge extremely high prices for these condominiums. According to Bain, “those at the top end of the income structure can out-compete others in the housing market, resulting in ever-escalating markets that fewer people can attain. The trends can help to explain the declining willingness of private developers to construct rental building that tend to be occupied by lower-income population” (Bain 239) As such, False Creek has become a neighborhood accessible to only those who can afford the high costs of living there.

Furthermore, because people who live in False Creek tend to be better off, the shopping available here comes at a premium. For example, most low-income earning individuals could not afford to buy groceries here. As such, they are deterred to an even greater extent from even coming to False Creek because not only can they not afford to live there, but also they cannot afford to frequent the shops. Effectively, False Creek has become an enclave where wealthy individuals are concentrated and poorer individuals are deterred from entering. This is a landscape that spatially polarizes socioeconomic classes in Vancouver. Many people who are employed in the service industry are forced to live further away from their inner-city jobs in places like Surrey and Richmond.

Thus, while the relocation of industries with jobs suitable for the knowledge-based class has been beneficial in revitalizing and sustaining Vancouver’s economy, it has also been detrimental to lower income groups, who now struggle to find viable employment and housing in Vancouver. These negative impacts of redevelopment and gentrification are part of what Florida labels as “the externalities of the creative age” (Florida, Cities and the Creative Class 171).

Removal of Industrial Infrastructure

While, de-industrialization has allowed other sectors of Vancouver’s economy to flourish, there are many problems associated with the removal of industrial infrastructure in False Creek. As a result of an international trend of the shrinking of the role of many Western governments and the deregulation of the economy, especially with regards to removing tariffs and abolishing trade protectionism, many factories have been relocated to countries where cheap labour is at a premium. In turn, many North American cities that were once regarded as important sites of production have undergone a process of de-industrialization. These waterfront neighbourhoods, where the means of production were once located, have been largely revitalized into desirable, modern living spaces. Such is the case for Vancouver’s False Creek neighbourhood. Its geographic location, being conveniently located on the water, made it a viable inner-city location for heavy industry. However, as Vancouver has transformed into a post-industrial city, False Creek by extension has been transformed into desirable waterfront real estate that only those with great financial means can buy into. Thus, the first problem associated with the removal of industrial infrastructure is the subsequent gentrification these neighbourhoods undergo, which serves to further polarize different socioeconomic classes in Vancouver.

Additionally, the removal of these industries serves to further polarize socioeconomic classes in Vancouver as it leads to “chronic structural unemployment” and essentially further limits the amount of places there are for low-income groups to work at or visit in Vancouver (Heikkila and Hutton 48). Chronic structural unemployment has come about because jobs that these people were originally trained for simply no longer exist. As these production jobs have be removed from the inner city, it has become an environment where the only people who have a reason to visit the inner city are those belonging to the knowledge-based class. In recent years employment opportunities for those who do not belong to the knowledge-based class are extremely limited, except in the service industry (Florida 104). Vancouver, like many North American cities has lost thousands of production jobs due to immense de-industrialization.

Possible Solutions to Combat Negative Externalities of Gentrification in False Creek

Strictly enforced municipal zoning policies could be implemented in False Creek that require a higher percentage of units allocated for low-income groups in each new building. This inclusionary zoning policy would act by stipulating a price cap on a number of units per new building that would allow lower-income earners access to False Creek living. These affordable units could be reserved for people in Vancouver’s growing service sector, who earn considerably less than those a part of the knowledge-based class. Furthermore, False Creek residents and other Vancouverites should be incorporated to a greater extent in the land-use planning process. Mark Keer discusses how the incorporation of public opinion throughout the late 1990s and early 2000s during initial planning phases of Southeast False Creek helped to stop plans that aimed at developing the area into a socially exclusive mirror image of the developments in North False Creek (Keer 330). By incorporating public opinion in city planning the process becomes more democratized and the landscape of Vancouver will start to reflect the will of the popular majority, rather than a few city planners and private developers.

While it may be unwise for Vancouverites to cling onto Vancouver’s industrial sector, due to international economic trends. Again, municipal zoning policies may help curb some of the negative externalities resulting from redevelopment in False Creek. Heikkila and Hutton offered an interesting report on the costs and benefits of relying on an “exclusionary zoning policy” in Vancouver. A policy like this would inhibit redevelopment and land use that is detrimental to industry (Heikkila and Hutton 49). This policy could be implemented to target specific key industries that are lucrative and employ large numbers of Vancouverites. Meanwhile, other plots, in the same neighbourhood, could be redeveloped to encourage new forms of land usage and revitalize the community. Therefore, specific zoning policies could transform False Creek into a neighbourhood with many diverse land-uses, would encourage diversity and potentially reverse some of the polarization that has occurred in Vancouver due to Gentrification and de-industrialization.

In addition, Vocational training for those left unemployed by deindustrialization should be a priority for policy makers. Perhaps by implementing programs that offer financial relief for these programs, more people would be inclined to go back to school.

Work Cited

Bain, Alison. "Re-Imaging, Re-Elevating, and Re-Placing the Urban: The Cultural Transformation of the Inner City in the Twenty-First Century." Canadian Cities in Transition. Fourth Edition. Ed. Trudi Bunting, Pierre Filion and Ryan Walker. Ontario: Oxford University Press, 2010. 262-275. Print.

British Columbia Statistics. False Creek 2006 Census. http://www.bcstats.gov.bc.ca/StatisticsBySubject/Census/2006Census/ProvincialElectoralDistricts.aspx

City of Vancouver. Policy Report Urban Structure "UB-1". http://former.vancouver.ca/ctyclerk/cclerk//20090728/documents/csbuub1.pdf

City of Vancouver. Southeast False Creek Creek Location. http://vancouver.ca/docs/sefc/policy-statement-1999.pdf

City of Vancouver. Southeast False Creek History. https://vancouver.ca/home-property-development/southeast-false-creek.aspx

City of Vancouver. Southeast False Creek Official Development Plan. https://vancouver.ca/docs/sefc/official-development-plan.pdf

Commonwealth BUFO Incorporated. Interpretive Strategy Southeast False Creek. http://vancouver.ca/docs/sefc/interpretive-strategy.pdf

False Creek History. http://www.culturalcurrency.ca/sitehistory.pdf

False Creek Homes and Location. http://falsecreekhomes.com/area-details.html

False Creek Transportation -Green Urbanism and Ecological Strategy. South East False Creek. http://courses.umass.edu/greenurb/2007/freilicher/innovations.htm

Florida, Richard. Cities and the Creative Class. New York: Routledge, 2005. Myilibrary. Web. November 8, 2012.

Florida, Richard. Who’s Your City?: How the Creative Economy is Making Where You Live the Most Important Decision of Your Life. New York: Basic Books, 2008. ebrary. Web. November 8, 2012.

Grant, Benjamin. June 17, 2003. "PBS Documentaries with a point of view: What is Gentrification?". Public Broadcasting Service. http://www.pbs.org/pov/flagwars/special_gentrification.php.

Heikkila, Eric, and Thomas Hutton. "Toward an Evaluative Framework for Land Use Policy in Industrial Districts of the Urban Core: A Qualitative Analysis of the Exclusionary Zoning Approach." University of British Columbia 23.1 (1986): Pages 47-60. Print.

Keer, Mark. “Spaces of Transition Spaces of Tomorrow: Making a Sustainable Future in Southeast False Creek, Vancouver.” Cities 24. 4(2007): 324-334. SciVerse. Web. November 8, 2012.

Mills, Caroline Ann. “Interpreting Gentrification: Postindustrial, Postpatriarchal, Postmodern?” Diss. The University of British Columbia, 1989. Print.

Rowthorn, Robert, and Ramana Ramaswamy. "Deindustrialization–Its Causes and Implications" <http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/issues10/issue10.pdf>.

Skaburskis, Andrejs and Markus Moos. "The Economics of Urban Land." Canadian Cities in Transition. Fourth Edition. Ed. Trudi Bunting, Pierre Filion and Ryan Walker. Ontario: Oxford University Press, 2010. 225-242. Print.

Southeast False Creek Transportation Study. http://www.tc.gc.ca/eng/programs/environment-utsp-southeastfalsecreektransportation-1014.htm

Stiftel, Bruce, Vanessa Watson, and Henri Acselrad. Dialogues in Urban and Regional Planning,. London: Routledge, 2007. Print.

Tetrad. Southeast False Creek Demography. http://www.tetrad.com/software/pco/

Vancouver Economic. http://www.vancouvereconomic.com/page/tourism

Vancouver Sun. Finlayson,Jock: "Opinion: Metro Vancouver’s economic well-being needs work". http://www.vancouversun.com/Business/2035/Metro+Vancouver+economic+well+being+needs+work/7268534/story.html