Course:GEOG350/2011ST1/Group 4 SEFC

Southeast False Creek

Group Members

Fionnuala Fordham , Sarvenaz Jahankhani, Hayley Macgregor, Donna Pasin, Man Hin Ruby Wong

Overview of Southeast False Creek Neighbourhood

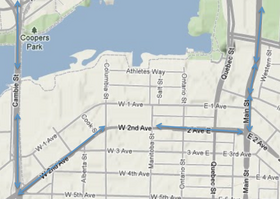

The neighbourhood of Southeast False Creek is located “between 1st Avenue and 2nd Avenue, to the south, and between 1st Avenue, Quebec Street, Terminal Avenue, and Main Street to the east” (http://vancouver.ca, About the Neighbourhood) in the city of Vancouver.The future development of this parcel formally known as the 2012 Olympic Village is zoned for use to facilitate a community supporting work/life balance using high density structures to support a large range of living

..

History

Southeast False Creek has a history dating back several thousand years, and had a creek “five times its present size (extending north to what is now Pender Street, and east to Clark Drive)” (http://vancouver.ca, Olympic Village/History). Over the years, due to the effects of urban sprawl, the neighbourhood has changed drastically. It has experienced several changes, ranging from being a home to the early settlers who used the land in 1859 to being an industrial and manufacturing workforce in the 1900s, and is now a modern residential community consisting of high-rises and retail spaces. Southeast False Creek has a history of mixed-use properties, which mainly consisted of heavy industrial properties, such as sawmills, shipyards, metal-working shops, salt distribution centers, and warehouses (http://vancouver.ca, About the Neighbourhood). Southeast False Creek was a large parcel of undeveloped industrial land before it became the home of the 2010 Winter Games.

Demography

During the First and Second World Wars, Vancouver’s population quadrupled, leading to an exponential population growth in the False Creek region. In the early 1970s, Southeast False Creek emerged as a significant industrial and commercial area, by way of ship-building, sawmills and lumbering, creating vast job opportunities and attracting skillful workers to the community. However, the industrial decline in False Creek during the mid-1970 to 1990s which leads to the migration of the industries. As a result, the city of Vancouver had rezoned the area in False Creek for housing and recreational facilities. The price of housing and the built-form of residential development are essential in explaining the change of population in False Creek.

Before the 1980s, the area had more family housing and most of them were low-rise units which were suitable for families with children. As the city project on rezoning False Creek region, the historical census data reflected some significant changes in the demographic pattern along with the structure change in built-forms. From the 1980s, the city focused more on high rise residential development that was targeted on non-elderly singles and high-income groups. In terms of households mix, families tended to have fewer children and more elderly. While in terms of age mix, there were considerably more middle-age individuals than children in the region. For income mix there were a higher proportion of high-income groups than low-income groups.

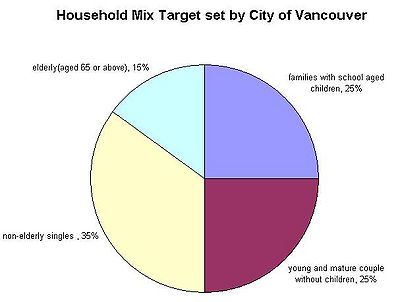

“In terms of household mix, the City set the following targets for households:

- 25% were to consist of families with school-aged children;

- 25% were to be young and mature couples with no school-aged at home;

- 35% were to be non-elderly singles;

- 15% were to be elderly (65 years and over).”

(City of Vancouver, False Creek South Shore: Evaluation of Social Mix Objectives, June 2001)

In the late 1980s, the city of Vancouver launched a “New neighborhood” project in Southeast False Creek to increase the housing capacity to meet the needs of the growing population. The project introduced a different objective in order to build a balanced housing mix for accommodating a range of income groups, household types and age group (City of Vancouver, Southeast False Creek Official Development Plan, April 2007). Currently, there are still series of residential buildings underdeveloped on the waterfront side in Southeast False Creek and approximately 6200 residential units will be built in the future; which estimated to bring 10,000 to 12,000 people to the neighborhood.

Characteristics of the Built-form and Transportation Infrastructure

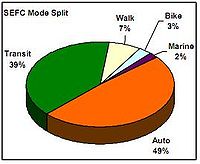

The Figure 1 Mode of Transportation SEFC Southeast False Creek engages a key piece of the waterfront real estate, which is adjacent to the city’s downtown core. This site is a redeveloped, 36-hectare former industrial area. Currently, the built form of the residential component of this development area consists primarily of medium- and high-rise apartment buildings easily accessible by public transit, shops, services, and quick access to the busy waterfront and central city. The site’s development is focused on residential uses in multi-family units, but also includes commercial spaces for retail/service and offices.

The transportation infrastructure of Southeast False Creek consists of the major arterial routes of the Cambie Street Bridge, Main Street, and Second Avenue, connecting it directly to the downtown core and Central Broadway. This accessibility and close proximity allows for large traffic flows by vehicular and non-vehicular commuters. As stated in the Executive Summary of the Southeast False Creek Transportation Study, an estimated 50% of trips to and from the site are made by auto, with the rest made by public transit, walking, and bicycles, as shown in the mode-split chart.

There are several bike lanes, such as the Ontario, Seaside, Off-Broadway, and Adanac bike routes. The site is also situated close to Sky Train lines, street car lines, ferries and aqua buses, and a Greyhound bus station, resulting in sustainable transportation modes being available to the community. Some sustainable strategies offered to residents of Southeast False Creek are community transit passes, car-sharing services, and transit-oriented designs aimed at achieving long-term sustainability in transportation by calming traffic and reducing vehicular modes of commuting.

Social Housing and Environmental Sustainability Issues

In 1990, Vancouver’s city council proposed a program that was intended to address air quality in downtown Vancouver. The program was named “Clouds of Change” and targeted the area of Southeast False Creek, an undeveloped area in Vancouver. Clouds of Change acknowledged the shift that needed to occur in urban planning to preserve our environment. Sean Antrim addresses this proposal, stating that, “in the wake of increasing property values and decreasing affordability, mass commuting to and from the city on a daily basis was negatively affecting air quality in the region” (themainlander.com). Clouds of Change strived to develop communities that limited long-distance travel and reduced Vancouver’s environmental footprint.

Southeast False Creek has some of the best and most valuable waterfront property in Vancouver. Clouds of Change was of the first to address affordability in the area, but failed to do so successfully. Instead, there was a reoccurring theme that favoured real estate business and industry development over social housing. Skaburskis and Moos, in their article “The Economics of Urban Land,” discuss the relationship of proximity, access, and land value, stating that, “people may be willing to pay more for locations close to parks, views and quiet surroundings and less for locations close to municipal landfills or highway noise” (Skaburskis and Moos 2010). Clouds of Change was the first attempt to create affordable housing on highly-valuable land. The vision was there, but the commitment to the housing crisis in Vancouver was not at the forefront of the project.

While focusing our attention on environmental sustainability is vital for our world and for future generations, developers must account for the growing dilemma of affordable housing, particularly when speaking of low-income families. The social housing crisis in Vancouver has scarcely been addressed. According to the 2011 Vancouver Homeless Count, there are currently more than 1,600 people without homes in Vancouver. Additionally, one-third of Vancouver residents find locating affordable housing to be challenging. While it is recommended that individuals spend thirty percent of their total monthly income on housing requirements, growing prices have pushed Vancouver residents to spend upwards of fifty percent to meet the basic needs of housing for themselves, as well as families (gvrd.com). With less than two-thirds of residents being able to afford housing, Vancouver is quickly becoming a city that solely caters to those in high-income brackets.

Gentrification is another ongoing issue in Vancouver. In his article “New Divisions: Social Polarization and Neighbourhood Inequality in the Canadian City,” R. Alan Walks addresses how the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. One of his main arguments surrounds immigration in Canada. While immigration is high in Vancouver, this may help explain some of the discrepancies in family income in Vancouver. He states that, “relative to the incomes of native-born Canadians, recent immigrants (arriving in the previous 10 years) in Canada’s major metropolitan areas have seen their relative incomes drop by approximately 15 percent.” He concludes this thought by saying that, “this produces a pronounced divergence in income between members of visible minorities and the white population in Canada” (Walks,2010).

Walks goes on to address the expanding number of single-parent households. Those with children and only one income find it difficult to afford living in a desirable neighbourhood such as Southeast False Creek. “Those with higher incomes are able to outbid others for housing and location, thereby displacing low-income households from desirable neighbourhoods, driving up housing values, and contributing to greater neighbourhood segregation” (Walks, 2010).

Neighbourhood segregation is an important factor when discussing the future of Vancouver’s citizens, as well as the future of the city. Walks discusses how one’s neighbourhood is directly linked to leading a successful life. He says that, “Neighbourhoods provide a basis for the formation of social relationships and networks, determine accessibility to jobs and information, provide amenities and services and are a major context for living and understanding daily life.” He goes on to conclude that, with a limiting of access to these resources, comes a struggle to rise above the poverty line. This, he says, “leads to increased racial division, distrust, discrimination and social exclusion” (Walks,2010). An example of neighbourhood segregation and gentrification in Vancouver can be best seen on Vancouver’s Lower East Side.

After the Clouds of Change project failed to take off, it was proposed that the undeveloped land in Southeast False Creek be used to house the athletes competing in the 2010 Winter Olympics, which were held in Vancouver. Originally, when the bidding process first started, the development was proposed with a vision of creating an environmentally-sustainable and socially-responsible housing project. This was an opportunity to showcase our vision for the future of cities—one that meets the needs of the low-income population, while keeping environmental sustainability a priority. The development was called “a delightful and humane living environment for people of different ages, lifestyles, and economic backgrounds...most of the residents of this community will have the opportunity to express their identity as well.” It was also stated that, “they emphasized the defence and enhancement of the neighbourhood as a prevailing solution to reanimate the ‘placeless’ urban scene, to encourage local heritage, cultural diversity and security, and to revitalize ailing volunteerism and social support networks fundamental to fostering active communities” (Ley, 2010). This vision sounds appealing to many, especially in terms of reaching out to those with a lower socioeconomic status.

Unfortunately, the Southeast False Creek plan did not turn out as most had hoped. For the Olympic Village development in Southeast False Creek, intended to assist with the housing crisis in Vancouver, it was proposed that 33.3% of the units be used for affordable housing and 33.3% be used for “modest market housing,” with the rationale given that “This is based on ensuring a balanced community with a broad social mix and access to housing by all income groups” (City of Vancouver, 2005). The city also outlined the Green Building strategy to create a sustainable community with environmental targets that were to be met, such as water and energy conservation, optimum waste and recycling management, transportation access, and urban agriculture opportunities.

Based on the increased costs of creating a green building, the promise of affordable housing was revoked, leaving potential residents, once again, with little hope of comfortably residing in Vancouver. Reasons that this projects failed are linked largely to budget issues related to the development. Tracy Vaughan wrote an article outlining the project in Southeast False Creek, titled “Collaborative Practice towards Sustainability: The Southeast False Creek Experience,” in which she explains that, although the one-thirds housing policy would push the loss from $4 million to $28 million, the outcome would better reflect the needs of the region and the goal of community diversity in Southeast False Creek. However, developers did not look at it in the same way. Instead, they argued that the loss of profit that would come with the amenities tied to social sustainability would ultimately harm future generations, which would not be a sustainable practice (Vaughan, 2008).

As Vancouver actively strives to reduce its carbon footprint, the problem of affordable housing continues to soar. Unfortunately, however, the Southeast False Creek project failed to execute environmental sustainability at an affordable price, leaving hopeful residents still hoping for the housing crisis in Vancouver to be addressed.

Contributing Causes

If it had not been for massive cost overruns, the Olympic Village affordable housing project just might have been successful. Several factors contributed to the overruns, some of which were within the City’s control, though others were not. The removal of contaminated soil from the site, for example, was necessary for environmental and public health reasons, but delayed construction and added $20 million to project costs (Geller, 2010).

Decisions regarding the built form, although made prior to the onset of construction, also held financial ramifications. City planners suggested high-rise designs, citing the fiscal and environmental benefits of increased density, while residents sought to preserve the character of the neighbourhood and favoured lower building heights (Vaughan, 2008). The final design called for mid-range profiles. As such, however, unit floor plans were less repetitive than their taller counterparts would have been, requiring more construction time and reducing the ratio of rentable and saleable space to building size. Overall, these changes added an estimated 30% to the original budget (City of Vancouver, Administrative Report, February 17, 2009).

Another significant contributor to cost increases, however—one that could have been avoided—was the decision to require more stringent environmental sustainability regulations after development had already begun. Internationally recognized and respected, Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED®) promotes sustainable building practices through education and third-party certification. These certification levels range from “Certified” to “Platinum” (LEED’s® highest rating), based on a rubric of points awarded in categories such as energy and water efficiency. The City of Vancouver mandated LEED® Silver for the new housing units at Southeast False Creek in its original Bid for Proposals (City of Vancouver, Request for Proposals, 20). Mid-project, however, the requirements were changed to the more stringent LEED® Gold. This adjustment dramatically increased the cost per unit and resulted in massive construction overruns, making many of the units unfeasible for use as social and supportive housing.

The new Gold requirement was the result of a deal struck between the Millennium Development Corporation and the City, wherein the developer agreed to a string of concessions in exchange for the City’s approval of a re-zoning application that would allow increased building heights in selected areas of the Olympic Village (Vaughn,2008). Indeed, on October 17, 2006, the Vancouver City Council approved Millennium’s re-zoning application on the condition (among others) that “all buildings in the City Lands of Sub-Area 2A [Olympic Village] achieve the Southeast False Creek Green Building Strategy and meet a minimum LEED™ Gold” (City of Vancouver, Summary and Recommendations: Current Planning Department, October 17, 2006; City of Vancouver, Special Council Meeting Minutes, October 17, 2006). Later, in an administrative report to the City Council, project advisors detailed added expenses associated with the new requirement, explaining:

LEED® Gold requires thicker walls, high performance glazing, solar shades, ‘hydronic’ or water-based heating, a radiant heating system, and green roofs. These and other green initiatives have added about $5 million to the original estimate (7.7%) (City of Vancouver, Administrative Report, February 16, 2009, p. 3).

The installation of new technologies and materials intended to reduce carbon emissions, increase water and power efficiency, and improve indoor air quality benefits society as a whole. Although decreased fuel consumption saves the consumer money over time, these technological measures cost more up front. Compliance with new, greener building policies is currently encouraged in the private housing sector, but is becoming increasingly mandatory for publicly funded projects (McManus, Gaterell, and Coates 2009; Pickvance 2009). While a private developer may be able to pass along some of the increased costs to the consumer by charging a somewhat higher home price but still be subject to market conditions, social housing has no such option. Any increased costs, therefore, must either be absorbed by the governmental housing authority or by increasing rent prices (Pickvance, 339). An increase in rent defeats the purpose of low-income housing, however, leaving the governmental absorption of losses—passed along to the taxpayer—as the only real option.

Recommendations

As the City of Vancouver struggles to find an answer to the social housing crisis, it may be beneficial to mirror programs that have been successful in other countries. The Million Programme was a project implemented by the Swedish social democratic party. The idea was to build one million new homes within a ten year period with the aim to provide affordable housing to all. Before the building began, there were a large number of old underdeveloped buildings that were demolished to help transform the previously undesirable neighbourhood. When the project was complete, 650,000 new modernized apartment type homes were accessible to families of various incomes (Borgegard, Kemeny 2004). Vancouver might take this idea and apply it to a neighbourhood such as the Lower East Side. By doing so, we would be substantially increasing access to affordable housing in the area, as well as transforming what has been long known as one of the poorest neighbourhoods in Canada. Giving opportunity to those who struggle will help maintain a sense of community in all of Vancouver’s neighbourhoods.

In these times of financial crisis, the City of Vancouver can ill afford to absorb all of the losses associated with the construction of the Olympic Village housing units. Indeed, not all of the overruns were within the City’s control. In the future, however, we must takes steps to ensure fiscal responsibility and an equitable balance between environmental and social sustainability. The City of Vancouver should continue to implement compliance with green building strategies for publicly funded projects and require the construction of social housing units as a condition of approval for new development. However, the City must acknowledge the increased expenses associated with new environmental requirements and budget sufficiently for them. We should continue to seek and facilitate collaboration between the general public, resident advisory groups, City planners, City Councillors, the Mayor and developers. The consultation between these mentioned parties should be utilized well in advance of any new major development and refrain from making costly changes to construction requirements mid-project.

Bibliography

- Antrim, S. Whose Village? A Brief History of the Olympic Village Development. The Mainlander. http://themainlander.com/ [accessed June 17-Aug 4, 2011].

- Borgegård,L., and J. Kemeny. Sweden: 2004. High-Rise Housing for a Low-Density Country.

- City of Vancouver. Administrative Report to Vancouver City Council, February 16, 2009. http://vancouver.ca/ctyclerk/cclerk/20090217/documents/a10.pdf [accessed June 17, 2011].

- False Creek South Shore: Evaluation of Social Mix Objectives. June 2001. http://vancouver.ca/commsvcs/housing/pdf/fc96replong.pdf [accessed June 12, 2011].

- Policy Report: Building and Development, January 17, 2005. http://vancouver.ca/commsvcs/southeast/odp/pdf/sustainabilityindicators.pdf [accessed June 14, 2011].

- Request for Proposals for the Development of Southeast False Creek Sub-Area 2A Including the Olympic Village. http://vancouver.ca/ctyclerk/cclerk/20060404/documents/a44RFPFinal.pdf [accessed June 17, 2011].

- Rezoning: 51-85 and 199-215 West 1st Avenue, 1599 -1651 Ontario Street and 1598 -1650 Columbia Street (Olympic Village site), Summary and Recommendations: Current Planning Department, October 17, 2006. http://vancouver.ca/ctyclerk/cclerk/20061017/documents/phmin.pdf[accessed July 28, 2011].

- Southeast False Creek: About the Neighbourhood. http://vancouver.ca/commsvcs/southeast/neighbourhood/index.htm [accessed June 12, 2011].

- Southeast False Creek Height Review. http://vancouver.ca/ctyclerk/cclerk/20100622/documents/p1.pdf [accessed June 14, 2011].

- Southeast False Creek Official Development Plan April 2007 http://vancouver.ca/commsvcs/bylaws/odp/SEFC.pdf [accessed June 12, 2011].

- Southeast False Creek Transportation Study: Executive Study. http://vancouver.ca/commsvcs/southeast/documents/pdf/transportexecsumm.pdf[accessed June 12, 2011].

- Special Council Meeting Minutes, October 17, 2006. http://vancouver.ca/ctyclerk/cclerk/20061017/documents/phmin.pdf[accessed July 28, 2011].

- Geller, Michael. Michael Geller’s Blog. http://gellersworldtravel.blogspot.com/ [accessed June 11-17, 2011].

- Images

- Graffiti on Wall. http://www.utne.com/blogs/blog.aspx?blogid=26&tag=poverty

- Homeless Mother with Children. http://homelessinvancouverbc.wordpress.com/category/uncategorized/

- Little Girl with Orange Poster. http://thetyee.ca/News/2009/10/16/RenovictionCity2/

- Lynch, N., and D. Ley (2010). The Changing Meanings of Urban Places. Canadian Cities in Transition: New Directions in the Twenty-First Century (4th Ed.).

- McManus, A., M.R. Gaterell, and L.E. Coates. 2010. The potential of the Code for Sustainable Homes to deliver genuine “sustainable energy” in the UK social housing sector. Energy Policy 38 (December): 2013-2019.

- Metro Vancouver. Draft Regional Affordable Housing Strategy Consultation Materials 3, August 2007. http://www.metrovancouver.org/planning/development/housingdiversity/AffordableHousingStrategyDocs/DraftAffordableHousingConsultationMaterials.pdf [accessed June 14, 2011].

- Metro Vancouver Homeless Count-Preliminary Report, May 20, 2011. http://www.metrovancouver.org/planning/homelessness/ResourcesPage/MetroVancouverHomelessCount2011PreliminaryReport.pdf [accessed June 14, 2011].

- Pickvance, C. 2009. The construction of UK sustainable housing policy and the role of pressure groups. Local Environment 14, no. 4 (April): 329-345.

- Skaburskis, A., and M. Moos (2010). The Economics of Urban Land. Canadian Cities in Transition: New Directions in the Twenty-First Century (4th Ed.).

- Simon Fraser University. Southeast False Creek Mobility Centre: Feasibility Study. http://www.sfu.ca/cscd/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/southeast_false_creek_mobility_centre_feasibility_study_000.pdf [accessed June 14, 2011].

- Transport Canada. Southeast False Creek Transportation Study: Sustainable Transportation for a Sustainable Community. http://www.tc.gc.ca/eng/programs/environment-utsp-southeastfalsecreektransportation-1014.html [accessed June 12, 2011].

- Vaughan, Tracy. Collaborative practice towards sustainability: The Southeast False Creek experience. Master’s thesis, Simon Fraser University, 2008. http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/handle/1892/10265 [accessed July 28, 2011].

- Walks, R. Alan (2010). New Divisions: Social Polarization and Neighbourhood Inequality in the Canadian City. Canadian Cities in Transition: New Directions in the Twenty-First Century (4th Ed.).