Course:GEOG350/2011ST1/Group 2 DTES

Group Members

Daniel Chow , Pauline Liang , Amy Muranetz , Chelsea Walley , Chang Zhou

Introduction

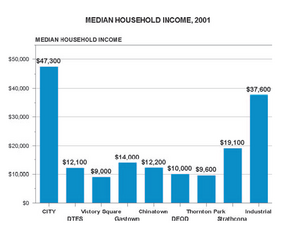

Vancouver’s Downtown East Side is generally regarded as the neighbourhood bordered by Cambie Street to the West, Heatley Avenue to the East, Alexander Street to the North, and Pender Street to the South. The area has often been criticized for being involved with drug trafficking, sex trade, and other crimes. Most of the residents who live in the neighbourhood are male, and the median household income is only one-eighth of the median income in Vancouver[1]. The Globe and Mail even named the neighbourhood “Canada’s poorest postal code.” The city of Vancouver and the provincial government have made many attempts to gentrify the area. For example, the newly reconstructed Woodward’s building brought in a new campus for Simon Fraser University, a new shopping centre, and a luxurious apartment.

Hastings Corridor is the area along East Hastings Street from Heatley Avenue to Clark Drive. The corridor was the major streetcar route and it helped shape the development of the city along the corridor. However, the corridor was not as significant in the twenty-first century and there are discussions to gentrify the area (Smith, 497)[2].

Because there are many attempts in drawing boundaries for these neighbourhoods, this project will use Byron Plant’s definition of the neighbourhoods [3] to introduce the development and gentrification process of the DTES and the Hastings Corridor, and to analyze the issues surrounding the neighbourhood, such as social housing and rising rental rates. The boundary of the neighbourhood, Downtown-Eastside Oppenheimer, is shown in the graph attached on the left, which are bounded by Alexander Street on the north, Heatley Avenue on the east, Hastings Street on the south, and Main street on the west. There is also a small extended area to the west of Hastings Street to Carrall Street.

Background Information

History

The Downtown Eastside (DTES) has a unique history, from very early on in the development of the city it has been Vancouver’s primary low-income neighbourhood. Around the 1880s and 90s, the DTES, then known as the East End, first began to develop, largely due to industrial and resource-based activities. It was a mixed industrial, commercial and residential area, populated by many different ethnicities and class backgrounds, though the majority of residents were men. The neighbourhood grew and developed throughout the early 20th century but, after World War II, began to decline as the economic center of the city shifted further west and industry sought cheaper land prices outside the city core. The decline of public transportation in the area soon followed, significantly impacting the remaining businesses, leading to further decline. By the mid 1960s the Hastings Corridor was known as Skid Road, a place populated by single, unemployed and often drug addicted men, notorious for its dubious morality and rundown residential hotels (Dobson)[4].

Starting as early as the 1940s, city planners were looking to clean up and redevelop the DTES. The Marsh Report, released in 1950, proposed that the entire Strathcona District be demolished and replaced with planned urban communities. The conditions of the DTES were considered intolerable and dangerous for the health and morale of the city, it was thought that the only effective method of clearing the ‘slums’ of Strathcona was their complete removal (Plant 6)[3]. Based on the Marsh Report, the city of Vancouver went on to create its own housing plan, the 1958 Vancouver Redevelopment Project, which focused on the widespread demolition and development of the DTES. Though the project was fought by many residents and local businessmen the city succeeded in clearing six residential blocks for redevelopment (Plant 7)[3]. A second urban renewal project was initiated in 1965; it cleared 29 acres of land and displaced 1,730 people from the DTES (Plant 8)[3]. Fought by local community groups, the redevelopment projects of the mid 20th century were never fully implemented and failed to transform a significant portion of the physical and social environment of the DTES.

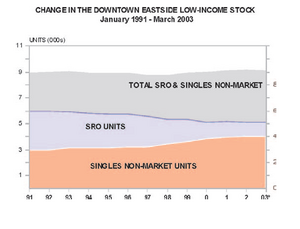

The DTES faced further challenges in the 1980s and 90s as Vancouver prepared to host Expo 86. In preparation for the influx of tourists, many landlords evicted and displaced the residents of Single Room Occupancy (SRO) housing in the Hastings Corridor, though many were able to return to their buildings after Expo 86 ended (Dobson 4)[4]. For some districts in the DTES the change was not temporary; in Gastown many buildings were upgraded and renovated in anticipation of the Expo and as an attempt at revitalizing the area. This lead to the loss of around 2,000 low income housing units and increasing rent prices in other areas (Smith 499)[2].

It was during this push for gentrification and revitalization in Vancouver’s DTES that the Hastings Corridor really began to develop a distinct neighbourhood identity. Those who had once been residents of Gastown’s SRO and social housing units were being pushed out into nearby neighbourhoods, including the Hastings Corridor. The decrease in social housing units led to a subsequent increase in the homeless population of the Hastings Corridor in the early 1990s (Dobson 4)[4]. The Hastings Corridor came to be recognized as distinct from other areas of the DTES for due to the prevalence of drug use and addiction, HIV/AIDS infection, violent crime, poverty, homelessness and abandoned businesses (Smith 500)[2].

Recent Developments

In 2000, the city of Vancouver signed the Vancouver Agreement, a policy promoting ‘revitalization without displacement.’ The idea is to upgrade or rebuild existing buildings while maintaining the same number of SRO and social housing units, and preserving the existing cultural and community balance (City of Vancouver Planning Department)[5]. The goal of this program is to encourage the development of new businesses, attract moderate income households, and improve the quality of, and access to, social services in the area. However, while market housing was slated to increase, social housing options were capped at existing levels. This This strategy fails to account for the growing need for affordable housing in the DTES as it is the area where most social housing is being relocated (Smith 504)[2]. There is also concern that the revitalization projects happening in other DTES neighbourhoods cannot occur without the displacing current social housing occupants, leading to the further marginalization of the DTES’s most vulnerable residents (Plant 10)[3].

Demographics

As the Hastings Corridor is no longer considered a distinct neighbourhood by the city of Vancouver, instead being counted as part of Strathcona, it is difficult to get demographic information about only the Hastings area. For this same reason it is also difficult to find any information that allows the comparison of the demographic composition of the Hastings Corridor in recent decades to the present. However, general inferences can be made based on data for the entire Downtown Eastside district and studies performed by researchers.

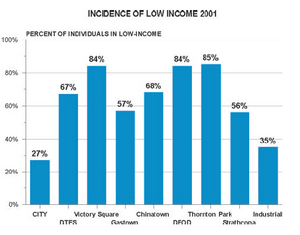

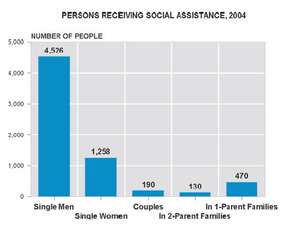

The population of the DTES, and especially of the Hastings Corridor, has always had greater numbers of men than women. A significant proportion of DTES residents are low-income singles living in residential hotels and other low income housing alternatives (City of Vancouver Planning Department). In a study on demographic trends in Single Room Occupancy (SRO) housing in the DTES, it was found that 79% of residents were male, and that the average age of tenants was 46 years old, 35-54 year olds making up 64% of the residents (Lewis et al. 2)[6]. In the city of Vancouver, the median age is only 38.6 years old and 35-54 year olds represent only 32.6% of the population; residents of the DTES, then, are considerably older than the rest of the city (Statistics Canada). There are many other statistically significant differences in the population of the DTES when compared to the city of Vancouver as a whole. In the DTES 82% of residents live alone, 14% of residents report being of Aboriginal descent, only 7% of residents are children and the average, pre-supplement income is only $6,282 annually (Brethour)[1]. In contrast, in Greater Vancouver as a whole, only 38.6% of residents live alone, 2% of the population identifies as Aboriginal, 17.9% of residents are 19 and under and the median income of all households in 2005 was $47,299 (Statistics Canada). Because residents of the DTES so often live alone, and have such low incomes comparatively, they find themselves more vulnerable to changing economic conditions and shifting housing markets. There is no second income or built up savings to fall back on if the rental market shifts abruptly and this can leave residents facing homelessness, especially in the uncertain economic conditions of recent years after the global market crash in 2008.

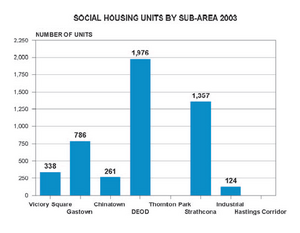

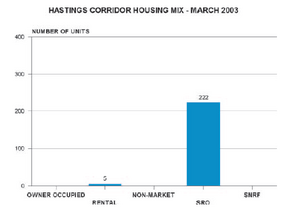

Urban Form

There are three main distinctive features in the built form of the Hastings Corridor; a prevalence of SRO and social housing units, the age of the buildings and a lack of businesses in the neighbourhood. The DTES has almost 80% of the low income housing units in the downtown core and roughly half of the housing units in the DTES are non-market, compared to only 8.5% of housing in Vancouver (Dobson 5)[4]. There were 227 social housing units located in the Hastings Corridor area as of March 2005 (City of Vancouver Housing Department 65)[7].. Hastings has recently been targeted as a potential site for the relocation of social housing units from other areas of the DTES, which are undergoing gentrification, in order to maintain the 1-for-1 social housing replacement goals of the city. Hastings Corridor is considered an attractive option for social housing relocation because land prices in the western DTES are rising and it is considered to be more cost effective and affordable in the Hastings area. Gentrification in Gastown and other DTES neighbourhoods is one of the main drivers for moving SRO and other social housing alternatives to areas like the Hastings Corridor. Developers in these areas are looking to attract people with moderate incomes who can afford to pay higher, market value prices and will revitalize the neighbourhoods. Social housing units, and their residents, are often considered to be detrimental to the profits of developers as mixed income buildings might be off-putting to some potential buyers.

Another main characteristic of the Hastings Corridor area is the age and condition of the buildings, especially SRO and social housing apartments. The average age of SRO buildings in the DTES is over 90 years old (City of Vancouver Housing Department 23)[7]. Many of these buildings have seen minimal upgrading and renovation over the years and this can have detrimental effects on the health and safety of residents. Between 2000 and 2002 there was a push by the city of Vancouver to improve inspection, regulation and enforcement in the social housing units in the DTES and this has led to some renovations and closures (City of Vancouver Housing Department 23)[7]. While it is important that the housing units be well maintained, the closure of social housing units can create further problems if they are not quickly replaced. These social housing buildings also form a distinctive part of the appearance of the Hastings area, there are 11 different buildings with social housing units in the five block area that is the Hastings Corridor (City of Vancouver Housing Plan)[8]. These buildings also often have liquor stores, pubs or other businesses at ground level and these contribute to the overall atmosphere of the area.

When industry left the DTES after WWII, there was also a significant decline in other businesses in the area. In the Hastings Corridor today there are only a few types of businesses still in operation. The street level of Hastings is largely occupied by pawn shops, second-hand stores, 24 hour convenience stores and coffee shops. Commercial vacancy rates are also on the rise as these businesses, many of which are believed to be fronts for the drug trade, deter new, legitimate businesses (Smith 500)[2]. This creates a patchwork of empty storefronts, a distinctive feature of the Hastings area.

Transportation

Hastings Corridor transportation is dominated by personal-use automobiles; there is regular bus service along the route as well, as it is a main entry point into the downtown area. While there are pedestrian walkways and crosswalks available, there is little pedestrian traffic due to the minimal number of businesses along the street and the general lack of appealing ground level spaces.

Issue Analysis

In the Housing Plan for the downtown eastside (2005) produced by the City of Vancouver states that if we do not fix or replace the existing low-income housing, homelessness is most likely going to increase. The number of low-cost housing is shrinking as opposed to the rising numbers of homeless people. Many SRO (Single Room Occupants) buildings that mostly houses low-income singles are decreasing at an alarming rate. According to a study by the Pivot Legal Society between 2003 and 2005, 99 new housing units were developed, yet Vancouver lost 415 housing units for low-income singles. Many of these losses were attributed to conversions, rising rental rates, increased market development and poor conditions of these units[9].

One of the main reasons for the loss of low-income housing is due the rising cost of renting. Since 1994 the shelter allowance for people on social assistance has been the same at $325 per month so does the $185 living allowance (Eby) [9]. According to a low-income Housing Survey done in 2005, the number of rooms that was available at the welfare shelter rate of $325 amount dropped to 28 percent between 2003 and 2005 and in the course of the study there were only two rooms available at that rate out of 118 SRO buildings.

Another reason for the decrease in social housing in the DTES is the increased marketable interest in the area for development. A good example of this is the Woodward’s building where all the units were sold in just two days. International Village and the Carrall Street Greenway are also good examples of this kind of development resulting in the loss of SRO buildings. International Village is a shopping mall that is aimed at attracting shoppers with disposable income with its high-end stores and the Carrall Street Greenway is designed at strengthening and revitalizing the community. It includes green infrastructure and is aimed at achieving ‘environmental, economic, social and cultural sustainability’.

A substandard living condition of many buildings in the DTES is another deciding factor in the decline of low-income housing. According to the Pivot Legal Society study, the quality of many of the low-income housing was so poor that many people chose to sleep on the street rather than be in these units. Major problems like, lack of essential services such as heat, working toilets, hot water, running water, roofs and pipes, and non-functional elevators are prevalent in many of the DTES low-income buildings. Health problems stemming from mould, bedbugs and rats are also a major deterrent as landlords fail to address these issues. Landlords of these low-income housing units are also known to resort to extortion of guest fees from tenants, entry into the rooms without the permission of the tenants, wrongful seizures of private property and illegal eviction and any complaints posed against them goes to deaf ears and because of all these problems, many choose to brave the streets(Eby, 5)[9].

The number of people living on the streets poses serious problems as they reflect poorly on the city and the government. This is like a vicious cycle as many people complain about the number of people on the street but they do not consider the factors behind the reasons why people are homeless[10]

Causes and Issues

Despite the fact that the number of people living in poverty in Vancouver’s Downtown East Side has decreased significantly since 1994, this does not indicate that the root of the existing problems in the DTES is being resolved. According to Michael Goldberg, former research director for the Social Planning and Research Council of B.C., “fewer people are poor now than in 1994, but they’re nowhere what they should have been on the strength of our economy. For the poorest of the poor, there are fewer of them, but their lives are much worse. The Downtown Eastside of Vancouver is the poorest postal code in Canada.” The DTES has earned this negative reputation by its prevalent street violence, drug addiction, sex work and its large population of those with limited or no access to safe, affordable housing.

The social dilemma surrounding the issue of gentrification in the East Hastings Corridor has been one of contention for the last decade, as the DTES struggles to accommodate the rising population of those with no fixed address. As the DTES serves as one of the most affordable areas for lower income people renting in the city, the issue of development and gentrification heightens the escalating emotions of residents in the area. Where affordable and short-term Single Residential Units were within reach for lower income residents five years ago, they can now afford to live in only 12% of the 3,500 privately owned hotel rooms in their community (CCAP)[11].

The issue of gentrification in the East Hastings Corridor is intrinsically tied to the dramatic drop of social housing and single residential occupancies (SRO) for lower income residents in the community. Gentrification in the area proves to be a double-edged sword as although it can provide an economic injection boost into the area through the development of residential buildings and condos, it can be detrimental to the low-income population in the area. By attracting a higher income demographic along with subsequent services, businesses and amenities, this eventually drives up real estate values, making affordable accommodation out of reach for most lower income residents, resulting in resident displacement.

East Hastings Corridor Neighborhood

The approximate population in the DTES and East Hastings Corridor was 16,000 in 2006 (CCAP)[11]. Among the 16,000 residents, there are a high percentage of seniors, aboriginal people, people of Chinese ancestry, people with mental and physical disabilities, and people who use illegal drugs (CCAP). “About 70% of the residents have low incomes with the average less than $1,000 a month. About 700 are homeless. Most live alone and are renters (CCAP)[11].”

Jean Swanson, coordinator of the Carnegie Center Action Project, summarized reasons behind why the poor today are actually living in more hardship than thirty years ago. “It’s worse, a lot worse. People are homeless because they can’t get on welfare and can’t pay rent.” Thirty years ago, the poor were able to live on welfare with enough to eat and a stable shelter, but now they are desperate for a temporary shelter and fear everyday that the city might successfully convince the rich to move into their homes and “revitalize” businesses. Over the years, the Downtown Eastside has gradually been boarded up, due to the fact that low income residents there have lost a huge amount of purchasing power in the last three decades, due to the drastic decline in low wage work availability, pensions and welfare.

Two factors that are affecting the residents in the DTES are the:

- Financial Situations of Low Income Residents.

- Bylaws don’t account for the overpriced hotels.

Lower Income people have less buying power, making them vulnerable to the shifting policies by policy makers. With the city looking to increase development in the DTES, new owners are buying many of the current hotels, and despite the bylaws to replace 1-1 SRO’s, many new landlords are increasing the prices of month-to-month rates. Many of the residents in the DTES depend on welfare, which provides $610 per person, disability assistance at $906 per month, and old age pension at $1100 per month. People on welfare and disability are supposed to pay around $375 for rent, but many have to use their food money to pay higher rents. (CCAP)[11].

Many of these rooms used to be within reach, priced between $350-$400 dollars per month for a ten foot by ten-foot room. This leaves a welfare recipient $100-$150 per month for other expenses including food and other necessities. New owners of these buildings are raising the once affordable rates to $600-$700 per month, which places these SRO units out of reach to anyone dependent on welfare.

In the DTES, there are 5,000 SRO (residential hotel) units: 900 special needs housing beds, 2,100 owner occupied and market rental apartments and houses, and around 1,500 owned by the province and operated as supportive housing. (City of Vancouver Housing Plan)[7].

Allocated in the 5,000 SRO units is a combination of rental units ranging from affordable prices at $375 per month, to unreasonable rates of $700 per month (CCAP)[11]. These suites as Ivan Drury from the Downtown Eastside Neighborhood Council states are still technically classified as Single Resident Occupancy suites for those of the lower economic levels, even though they are well beyond financial availability for anyone on the welfare system (Drury)[12].

Of the 3,500 privately owned SRO units, many are ten foot by ten foot cramped rooms, with no kitchen appliances, bathrooms, or secure locking doors. These spaces are far from being fit for anyone, as many are over 50 years old, and infested with bed bugs and vermin.

Gentrification in the DTES

Gentrification in the East Hastings Corridor has two primary components driving its progress, and impacts the amount of available affordable social housing in the area. These two factors are:

- City bylaws and policy advocating development in the DTES

- Development of new residential buildings and condos

The provincial government has tried to revitalize the DTES economy by performing numerous actions throughout the years; however, the economically impoverished residents of the DTES rarely feel the benefits. For instance, the province helped by raising welfare rates in 2007 with monthly benefits for a single person increased to $610 from $510, and for a single parent with child to $946 from $846, but those represented the first hikes since 1992 and certainly did not account for inflation. Furthermore, with the excitement in hosting the Vancouver 2010 Olympic games, little concern had been placed on the social housing issue. Two years before the Olympic games, several residential hotels have been bought out by developing companies and rising rental costs have displaced hundreds with no affordable place to sleep.

City bylaws and policy advocating development in the DTES

City Policy and Classification of SRO’s

City policies surrounding available housing for low-income residents and new developments in the DTES has been under controversy for a few reasons. There are two fundamental problems with the City’s method in classifying housing units available to lower income residents. The first is that the city classifies hotel units with rents of $425 or higher as being available to low income people and included in the 5,000 SRO units available.

The second problem is the City classifies provincially owned hotel rooms, which are not self-contained or earthquake proofed as secure units of social housing. These buildings are used for social housing, but had residents already living there upon purchase, and this cannot be classified as new social housing units. The one for one policy cannot be considered accurate because it includes replacement unit’s hotel rooms that are not self-contained.

The DTES has approximately 10,000 residents who can only afford $375 per month on rent, as well as around 700 people without homes. The percentage of hotel rooms where all rooms rent for $375 or less dropped from 29% in 2009 to 12% in 2010. The number of vacancies in hotels renting rooms for $375 dollars or less dropped from 4 rooms in 2009 to half that number in 2010.

Though the city states the 1-1 policy ensures that no SRO units are lost, CCAP found the number of newly affordable units was 112 less than the number of closed hotels plus hotel rooms lost to rent increases above $375. This number is then reflected in a 12% increase in homelessness from 2008 when a survey was conducted in March 2010 (CCAP)[11].

Development of new residential buildings and condos

Provincially Owned Hotels

The province has bought and leased approximately 24 hotels with around 1,500 rooms since 2004. These hotels do not count as additional housing since they were already previously filled with residents (CCAP) [11]. The city does have a policy to replace every residential room that is lost to development, but this policy does not address the rising costs of living and stagnant minimum wage that has contributed to the rising number of those becoming homeless.

Approximately 1,842 condos and other market housing units are slated for construction in the DTES between 2003 and 2011. “Of these, 833 are completed, 959 are under construction, 248 are approved, and 215 are under review (CCAP)[11].” The development of condos in the East Hastings Corridor is the primary factor in the process of gentrification, and displacement of those without stable homes. With the increase of bigger condo developments, a richer demographic take over a neighborhood, replacing the lower income housing and services in the area. As more condos are developed, property values will rise, and hotels previously serving lower income residents convert to serve more lucrative markets.

As Ivan Drury of the Downtown Eastside Neighborhood Council also exclaimed, certain hotels in the DTES discriminate their services based upon stereotypes, appearances, and instead rent their rooms to students or tourists only (Drury) [12]. This discrimination is not recognized by the city, and is still counted in the 5,000 SRO units in the DTES.

Displacement of low-income Residents by Gentrification

According to the CCAP, the number of hotels renting for over $425 ($50 above what welfare renters can pay) has increased by 44% between 2008 and 2009. As a result, many DTES residents unable to rent on their own now pair up with another single resident to rent a single ten-foot by ten-foot room. “CCAP also found that the number of hotels where two people are staying in one tiny room quadrupled between 2008 and 2009” (CCAP)[11].

A rising number of hotels in the DTES are also showing an increase in the amount of vacant rooms, which usually suggests they are transitioning to sell the building, upgrade, or increase their rents. “These hotels include the Colonial (90 vacant units), and Argyle (40 vacant units). The Golden Crown (28 units) is empty and renovating as is the Burns Block (28 units)”(CCAP)[11].

Displacement of Low-Income Residents by Gentrification

According to the CCAP, the number of hotels renting for over $425 ($50 above what welfare renters can pay) has increased by 44% between 2008 and 2009. As a result, many DTES residents unable to rent on their own now pair up with another single resident to rent a single ten-foot by ten-foot room. “CCAP also found that the number of hotels where two people are staying in one tiny room quadrupled between 2008 and 2009” (CCAP)[11].

A rising number of hotels in the DTES are also showing an increase in the amount of vacant rooms, which usually suggests they are transitioning to sell the building, upgrade, or increase their rents. “These hotels include the Colonial (90 vacant units), and Argyle (40 vacant units). The Golden Crown (28 units) is empty and renovating as is the Burns Block (28 units)”(CCAP)[11].

New SRO Units under Construction

Along with units in the new Woodward’s building dedicated as SRO units (125 units) and for families (25 units), similar units are also under construction at Station Street (80 units), Hastings Street (39 units), Abbott and Pender (108 units), and 339 W. Pender (96 units) (CCAP)[11].

There are approximately 5,700 homeless, low-income and disabled residents in the DTES that need access to decent housing. Landlords have the right to raise rents when a new resident moves in, and it’s not surprising then that 415 rooms renting at the $375 mark or lower were lost between 2009-2010 (CCAP)[11].

Future Solutions

Nearly $40,000 is spent on each homeless person annually, with those funds being distributed on hospital visits, police calls and other services. According to an article in the Tyee, “If there are only 2,174 homeless people in the Vancouver area (an official figure everyone in the field assumes is well below the actual total) and if each person uses $40,000 in services (a figure that did not include all local services), then British Columbia taxpayers are spending $86.9 million a year just to help people living on the streets stay alive” (Tyee, 2007)[13]. The Tyee also stated that according to data, the average Canadian spends approximately $11,200 a year on housing, and supportive housing funded by the government, which includes social services, only costs around $28,000 a year.

This $28,000 housing figure in contrast to the nearly $40,000 spent on reactive measures for those without homes illustrates the redundancies of social housing policies in Vancouver and elsewhere.

Affordable social housing is not an issue the City of Vancouver can ignore much longer, as citizens groups, protesters and residents have expressed through organized protests, rallies, and campaigns. Leaving low-income residents to fend for themselves engenders generations of people to often seek illegal means of sustaining themselves, use drugs to cope, or relying on the prison system as a last resort.

The solutions to Vancouver’s housing issues in the DTES needs to shift from reactive measures of providing emergency support systems such as temporary shelters, to proactive measures of early intervention and prevention, such as the implementation of social programs and construction of future social housing projects.

Vancouver can also begin to fully utilize the precious greyfields, the land that have been under-utilized or abandoned, such as the closed shops and even brownfields, the land that are reusable for industrial and commercial facilities in the Downtown Eastside to fully benefit the residents there.To date, the city of Vancouver has not purchased any lots for social housing beyond 2013.

Vancouver's initiatives towards a solution

Local Social Programs

Many of the programs being implemented by Vancouver are being implemented at a more localized level through community programs and initiatives. One local program in Vancouver established in February 2010, the Downtown Eastside Connect is a community information centre in the DTES. Real life story telling sessions are held with the aim to improve the quality of life for the residents in the DTES. The general public and media will find the Downtown Eastside Connect provides a frank, informative perspective on the revitalization of a community deeply rooted in Vancouver’s history.

According to the City of Vancouver, “at least one quarter of the people found sleeping outside were aboriginal, compared to about two percent of the city population.” To reduce the numerous health concerns for the residents in the Downtown Eastside, Vancouver Coastal Health holds an Aboriginal Wellness Program, which provides culturally safe mental wellness and addictions programs for Aboriginal people. Wellness programs promote healing, are easy to access, meet the needs of the Aboriginal population and support an Aboriginal worldview. Working with others, they address social justice issues through education and advocacy so that urban Aboriginal people can receive supportive services and information.

Long-Term Actions

Revitalization without displacement policy

The four main components of this policy enacted by the City of Vancouver include replacing SRO’s with social housing units, supporting programs that help link those without jobs to employment within the community, providing access to government programs for low-income residents, and providing health care services, especially for those with drug or mental illness issues (City of Vancouver Housing Plan)[7].

Homelessness Action Plan

Homelessness Action Plan by the City of Vancouver seeks to create a collaboration between the city and local organizations to address income, housing, and support services and how they affect the rising homelessness issues, especially in the DTES. The report put out by the city states that Vancouver is only 450 units away from completely ending street homelessness by the year 2015, with another 750 units needed by 2020 (City of Vancouver Housing Plan)[7].

They address those who are homeless as, “those living on the street, sleeping in back lanes, parks, alcoves, etc; those staying in shelters or transition houses as temporary accommodation; and those who are ‘couch surfing’, staying with friends or family. The term also includes those at risk of becoming homeless because they are living in places which are not safe, secure or affordable” (City of Vancouver Housing Plan)[7]. One component of The Homeless Action Plan, “calls for an increase in the support component of income assistance to at least reflect the increased cost of living since 1991.”

Additional Supportive Solutions

A few other potential suggestions to examine in our solutions towards the social housing debate is:

- Community owned and organized Single Resident Accommodation Programs.

- Active involvement in social rehabilitation programs as requirements for renting, paired with effective rental control policies.

- Mixed social housing throughout the city, otherwise known as Scattered-Site Housing.

1.Single Resident Accommodation Programs

Single Resident Bylaw by the City of Vancouver means that SRO Hotel owners must first apply to Council for an SRA conversion or demolition permit. In addition, Vancouver runs The Supportive Housing Registration (SHR) service, which manages the process for tenants to be placed in the SRO units (VHU, 2009). The program has placed 146 people in homes since the service began operating in late 2008.

2. Social programs and rental control policies

Changes made to the BC Employment Assistance Program have made it increasingly difficult for those at risk to seek employment, as applicants must wait over three weeks to be eligible for assistance (City of Vancouver Housing Plan)[7]. Also younger applicants 19 years and older must demonstrate their financial independence before being eligible for hardship assistance. Increasing welfare rates to modest standard of living would enable most of those living on the streets the chance to rebuild their lives from within a safe, stable residence. The City of Vancouver has also stated concerns that the amount of assistance provided for individuals and families is not enough to sustain them, as the last increase for single adults was in 1991 (City of Vancouver Housing Plan)[7].

As one of the primary concerns for those on the welfare system is that rental rates are rising as their means of subsistence stays the same. Implementing rental control rate policies targeting the SRO’s in the DTES will ensure that the residents there are able to afford the rent for such places. Another option is to provide government subsidy grants to SRO’s to keep their rental rates the same, but helps provide the additional revenue needed for building maintenance, services, and property taxes.

3. Scattered-Site Housing

Scattered-site housing or clustered apartments disperse individuals and families into developments around the city, and offer the benefits of independence. The apartments are already part of the community, minimizing problems of siting and stigmatizing homeless families.

These scattered apartments or rooms provide a normal living context for those who reject living in an institutionalized or program setting, though as Barrow and Zimmer have concluded, “requires greater effort on the part of both the residents and service providers.”

One concern that has been expressed is that the concentration of low income housing in the DTES exaggerates the violence, drug use, and social ills of the neighborhood. The idea of integrating these residents throughout the city would as the Tyee has claimed, reduce the percentage of concentrated drug users, crime, and violence. An article in the Tyee stated, “individuals moved to so-called “scattered site” housing tend to reintegrate into mainstream society faster than those housed in large facilities in troubled neighborhoods such as the downtown eastside.” A successful precedent of the scattered site housing model is The Pathways to Housing Model as described by founder Sam Tsemberis in New York which, “provides housing first, and then combines that housing with supportive treatment services in the areas of mental and physical health, substance abuse, education, and employment[14]. Housing is provided in apartments scattered throughout a community.”

Some additional benefits of this model are seen in a few ways:

- As this model ensures that people with psychiatric disabilities are not all housed together in one building, it has proven to be a more cost-effective method to reintegrating the homeless with psychiatric disabilities into the community. Municipal costs per night to house the homeless are $1185 in a psychiatric hospital, $519 in an emergency room, $164 in jail, $73 in a shelter, or $57 in a Pathways Housing First assisted living program. Pathways has housed more than 600 people in the New York area alone, and the program maintains an 85% retention rate even amongst those individuals not considered "housing ready" by other programs.

- Sense of place and belonging in the community. This "scattered site" model helps provide clients with a sense of home and self-determination, and helps speed an individual’s reintegration back into the community. Varady and Preiser have also reported that clients in programs who transition from having no fixed address to having their own place value this immensely, and become highly motivated to keep their home (Varady et al)[15]. As they expressed, “Some people spontaneously begin to work on their sobriety and seek treatment as a way of improving their own well being, thereby increasing their chances for successful tenure.” Tenants in the building not involved with the scattered site program also help “provide a normative context for neighborly behavior”, and help them to participate in community events and living, that for many, have never been able to do so (Varady et al)[15].

Developers of scattered site supportive housing sometimes face intense resistance from not-in-my-backyard style neighborhood groups, which fear the arrival of recovering drug addicts or the mentally handicapped into their neighborhoods. For example, resistance was fierce to a recently rumored supportive housing project at Dunbar and 16th Avenue in Vancouver. Those fears reportedly spawned an anonymous group called NIABY: Not In Anyone's Backyard.

Precedents of Successful Housing Initiatives and Programs

Seattle’s Housing First Initiative combines housing with in-house medical and mental health services. In its first six months, the pilot program it has already been successful at moving roughly two-dozen chronic homeless, many of who have long-term addictions, off the streets. A report conducted by Substance Abuse Policy Research Program in 2009 found that, “ Providing housing and support services for homeless alcoholics costs taxpayers less than leaving them on the street, where taxpayer money goes towards police and emergency health care.” The report also found that the Housing First Initiative, through its integrated housing and social support system saved the city and taxpayers over $4 million dollars over the first year of operations (SAPRP, 2009)[16].

Conclusion

Decent housing and accommodation provides much more than just a sense of belonging and place, especially to those living in the Down Town East Side. It has also been shown to decrease drug, alcohol and mental health issues, and is more cost effective for the communities and taxpayers themselves. De Jong has noted, “It is as much as five times more expensive to shelter (in emergency shelters) and treat homeless people than it would be simply to house them properly (Bunting et al, 2008).

Finding pragmatic solutions to address the lack of affordable housing for low-income individuals and families is one that requires the deployment of various responses and programs to target its multifaceted complexities. SRO Housing Programs is the first step towards helping get those without an address get some form of stable housing, and get off of the streets. “Since 1979, a west-side single family home has increased in value by 480%, while median income has increased by just 9%” (City of Vancouver Housing Plan)[7]. Raising welfare rates to take into account inflation and standard costs of living, combined with rental rate control policies for low-income groups would help maintain the ability for most low-income people to secure affordable housing. As over 80% of Vancouver’s homeless have one or more health issue including addiction, mental illness, or other chronic illness, coupling a decent monthly stipend for living in conjunction with adequate social health services would lessen the anxiety faced by those both homeless and with mental health issues. Another pragmatic solution involves scattered-site housing, with additional onsite and visiting support staff for residents.

The right to access affordable and quality housing not only positively contributes to a communities sense of place, belonging, and self-worth, but is a more cost effective stance to take with all cases of social housing for the marginalized. As the UN has expressed, “Denial of the right to adequate housing to marginalized, disadvantaged groups in Canada clearly assaults fundamental rights in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedom (United Nations Rapporteur, 2009)[17].

Bibliography

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Brethour, Patrick. "Exclusize Demographic Picture." 13 February 2009. Globe and Mail Web site. 8 June 2011 <http://www.theglobeandmail.com/archives/article971243.ece>.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Heather, Smith. "Planning, Policy and Polarisation in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside" Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie. 94.4 (2003) 496-509.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Plant, Byron. "Vancouver Downtown Eastside Redevelopment Planning." Legislative Library of British Columbia (2008): 1-13.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Dobson, Cory. "Ideological Constructions of Place: The Conflict Over Vancouver's Downtown Eastside." Adequate & Affordable Housing For All: Research, Policy and Practice. Toronto: Center for Urban and Community Studies, 2004. 1-32.

- ↑ City of Vancouver Planning Department. "10 Years of Downtown Eastside Revitalization: a Backgrounder." 1 March 2009. Downtown Eastside Relitalization. 6 June 2011 <http://vancouver.ca/commsvcs/planning/dtes/pdf/DTESDirectionsbackgrounder.pdf>

- ↑ Lewis, Martha, et al. Downtown Eastside Deomographic Study of SRO and Social Housing Tenants. Vancouver: City of Vancouver, 2008.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 City of Vancouver Housing Department. Housing Plan for the Downtown Eastside. Vancouver: City of Vancouver, 2005.

- ↑ City of Vancouver. "Single Room Accommodation By-law No. 8733." 15 June 2010. Social Development Department: Housing Policy. 8 June 2011 <http://vancouver.ca/bylaws/8733c.pdf>.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Eby, David, and Misura, Christopher. Cracks in the Foundation, Solving the Housing Crisis in Canada's Poorest Neighbourhood. Sep. 2006. 14 Jun. 2011. <http://www.pivotlegal.org/sites/default/files/CracksinFoundation.pdf>

- ↑ Carrall Street Greenway <http://vancouver.ca/engsvcs/streets/greenways/city/carrall/index.htm.>

- ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 11.11 11.12 11.13 Pedersen, Wendy, and Swanson, Jean. Pushed Out: Escalating Rents in the Downtown Eastside. The Carnegie Community Action Project. 2010.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Drury, Ivan. Personal Interview. 8 Jun. 2011. Drury is part of the Downtown Eastside Neighborhood Council. Phone number: 604-781-7346

- ↑ Paulsen, Monte. Jan 8, 2007. The Tyee. Accessed July 31, 2011 <http://thetyee.ca/Views/2007/01/08/HomelessSolutions/>

- ↑ Pathways to Housing, Sam Tsemberis. New York, New York. Accessed Jun 5th,2011. <http://www.pathwaystohousing.org/content/our_model>

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Varady, David. Preiser, Wolfgang. “Scattered-Site Public Housing and Housing Satisfaction: Implications for the New Public Housing Program”. Journal of the American Planning Association. 1998. Vol. 64, Issue 2, pg 189-207. http://www.homelesshub.ca/Library/View.aspx?id=17781&AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1

- ↑ “Housing for Homeless Alcoholics Can Reduce Costs to Taxpayers,” Substance Abuse Policy Research Program, March 2009. Accessed July 29, 2011 <http://www.saprp.org/m_press_larimer033109.cfm>

- ↑ UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Adequate Housing U.S. Mission. Retrieved 31 Jul 2011<http://www.nesri.org/programs/un-special-rapporteur-on-the-right-to-adequate-housing-us-mission>