Course:FRST370/Projects/Exclusion of the Baka People's Involvement in Forest Management in the Sangha Trinational Landscape of Cameroon, the Central African Republic, and the Republic of the Congo

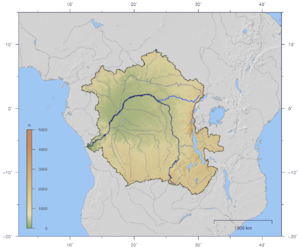

The Sangha Trinational Landscape (TNS) is nestled in the heart of the Congo Basin. It is home to the Baka and Aka, among many other peoples, where they have lived as hunter-gatherers in these central African jungles for many thousands of years. Throughout the 1990s, the governments of Cameroon, the Central African Republic, and Republic of the Congo began creating conservation reserves in these areas to protect the immense biodiversity found in the Congo Basin.[1] This led to the formation of the Sangha Trinational Landscape, a "transboundary conservation complex" in the heart of the Congo Basin.[2] It is a mosaic of conservation areas, where certain logging and hunting concessions can be administered by the government, and national parks, where natural resource use is prohibited. The formation of these protected areas, along with many laws restricting the collection of forest resources, have severely hurt the local Baka and Aka peoples.

The Sangha Trinational Landscape

History

The region that would become the Sangha Trinational Landscape (TNS) began attracting the international attention of scientists and conservationists in the 1970s due to its rich biodiversity.[3] At the urging of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) to protect this biodiversity, plans for a continuous patchwork of conservation areas in the Congo Basin began being drafted in the mid 1990s. In 2000, the TNS was born from this in a collaboration between Cameroon, the Central African Republic, and the Republic of Congo. In 2012, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) designated it as a World Heritage site.[2][3]

Countries

The TNS lies within the borders of Cameroon, the Central African Republic, and the Republic of Congo, and is situated where the three countries intersect.[2] All three countries have very high rates of poverty and are low on the human development index.[4] Forestry and oil are the main industries in this region.

National Parks and Protected Areas

The TNS was designed in a way that takes into account the large, continuous ranges that wildlife need, and the fact that wildlife does not obey national borders. This was done by creating adjacent reserves that form a transboundary continuum of protected land, surrounded by buffer zones intended to keep these reserves as separate from human impact as possible. In addition to conservation areas and buffer zones, the TNS includes three national parks[1] that total about 750,000 hectares in area.[2] These parks are:

- Lobéké National Park established 1999 in Cameroon

- Dzanga-Sangha National Park established 1990 in the Central African Republic[5]

- Noutabale Ndoki National Park established 1993 in the Republic of Congo

The Congo Basin and its Ecology

The TNS is located in the northwestern portion of the Congo Basin.[2] The Congo Basin is a depressed landscape that comprises the entire watershed for the Congo River. It is a forested region of 370 million hectares in Central Africa, that spans ten different countries across the continent. Like many other tropical forest regions, the Congo Basin is a biodiversity hotspot, with unique tropical forest ecosystems, many of which are being threatened by human activity.

The Congo Basin contains roughly one fifth of the remaining closed-canopy tropical forests in the world,[6] and the TNS works to protect these and ensure that they will continue to exist in the future. This region is home to many alluring wildlife species, including three out of four of the world's great ape species.[6] One of these is the western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla), a critically endangered species[7] that relies on the declining forests in the Congo Basin for its habitat. These are the facts that international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have used to justify the removal of indigenous people from the forests in the TNS.

Tenure Arrangements in the Congo Basin

Land tenure in the Congo Basin has its roots in colonialism. Though all the countries have achieved independence from their European colonizers, the colonial practice of the nation state having absolute control over all of the forests remains[8]. This means that in all three countries in the TNS, the nation state has statutory rights to the forest while the local people do not have any actual ownership of the land. Permits can be issued to individuals, communities, or organizations by the Ministry of Forests and Wildlife (MINFOF) in Cameroon,[9] the Ministry of Water, Forestry, Hunting and Fishing (MEFCP) in the CAR,[10] and the Ministry of Forest Economy, Sustainable Development, and Environment (MEFDDE) in the Republic of Congo.[11][12]

The Forestry Law was enacted in 1994 in Cameroon to improve policies relating to forest and natural resource management.[13][14] It was intended to help increase transparency in forestry management and give back to local communities by giving a few benefits to the communities immediately adjacent to the forests.[14] This law includes sections that state that the customary rights of indigenous peoples should be recognized in the absence of other statutory rights; however, these customary rights are not recognized in practice. Similar laws were enacted in the CAR and Republic of Congo during that time period.[11]

The Congo Basin Forest Partnership

The Congo Basin Forest Partnership (CBFP) is a “non-binding multi-stakeholder partnership”[15] among both domestic and international stakeholders, which lets members voluntarily cooperate and collaborate. It was formed to help improve the management of the Congo Basin forests and natural resources in a responsible and sustainable manner in addition to improving the living conditions of communities in the area.[16] This partnership gives a platform for the exchange of ideas and allows people within the partnership to have their values heard.

Membership

The CBFP is open for partnership to members from “states, international institutions and organizations, NGOs, research and academic institutions and private sector entities.”[15] Members are organized into seven distinct colleges based on the type of stakeholder and their role.

The seven colleges:[17]

- Regional college

- Civil society college

- International NGO college

- Private sector college

- Donor college

- Scientific and academic college

- Multilaterals college

Only members of the college can be on the CBFP council and participate in their meetings, which occur biannually (usually either in Europe or Central Africa) in order to discuss management strategies and policies.[17] To become a member, an organization must share the values of the CBFP and be willing to work within their framework. This process includes appointing a single point of contact and is free of charge.[18]

Lack of Involvement at a Local Level

Though the list of CBFP members includes stakeholders ranging in position from the presidents of participating countries to industrial logging companies, the local communities in the affected regions are noticeably absent from the list. This is significant because the CBFP is the platform that allows stakeholders from and operating in the region to give voice to their opinions and concerns. Without being a member of the CBFP, it is much harder for local communities (whether they are Baka, Bantu, or a different ethnic group) to have their voices heard. This also means that it is easy to exclude these communities from decisions made about the management of the forests. It is important to note that though there is not a way for the local communities to be directly involved, the CBFP implies that local communities could be represented through a third party organization by including "advocacy for the...well-being of local and indigenous communities"[18] as one of the possible ways a CBFP member can remain active.

Author's note: This page does not include a comprehensive list of the relevant partnerships and programs that exist in the region. There are many more, such as the Central Africa Forest Commission (COMIFAC,) the Congo Basin Program, and the Central Africa Regional Program for the Environment (CARPE,) some of which may include much better systems for incorporating local and indigenous people.

Affected Stakeholders

Affected stakeholders are groups of people (sometimes called social actors or user-groups) who are directly connected to the forest. They usually have a long history in the area and a great reverence and care for the specific forest, causing them to care deeply about the forest and what the future looks like for it. Oftentimes they have a long-standing ancestral connection to the land.

The Baka People

The Baka are hunter-gatherers who have lived in the western region of the TNS for tens of thousands of years. They are known by many other names, including Bayaka, Bebayaka, Bebayaga, and Bibaya, and are colloquially referred to as “pygmies,” though this term encompasses a much larger group of people including the Aka and Twa peoples. They speak a unique language called Baka which has Ubangian roots and is very different from other languages spoken in the region.

Lifestyle

The Baka are forest people. They have lived as hunter-gatherers in the jungles of the Congo Basin for thousands of generations, and they are deeply connected to these forests. Their religion is animistic and centers around a forest spirit called Jengi (also called Djengi or Ejengi)[19][20] and their cultural identity arises from their connection to the forest. They depend completely on the forest for their livelihood and wellbeing. Everything in their lives, from their food and tools to clothing and shelter can be made from things collected in the forest. They often hunt small forest animals such as duiker for bushmeat.[21]

Governance within the Baka

The Baka live in acephalous societies with an egalitarian structure. In these communities, everyone is considered equal, tasks are distributed evenly among people, and there are no appointed leaders. Their lack of a leader makes it difficult to come up with joint forest management (JFM) solutions (even if that was a goal of the government, which currently it is not) due to the lack of a single or small group of people to come forward to represent the community in making decisions. It means that they have no centralized point of decision making.

Rights

Since their ancestors have occupied the forests of the western TNS, the Baka people hold customary rights to these lands. However, these rights have not been recognized by the government, due to a lack of a system through which the Baka could claim them. Because of this disregard for their rights, the Baka have been pushed out of their traditional territory to make room for national parks and wildlife reserves.[22] Congolese law states that customary rights should be acknowledged, provided there are no other statutory rights to the land already in place. In this case, the governments of Republic of the Congo, CAR, and Cameroon claimed statutory rights to the land without allowing the Baka to first make their claims for their customary rights of tenure.

Though the Forestry Law enacted in Cameroon in 1994 was supposed to give communities around the forests some benefits in the form of royalties and community forest concessions, the Baka have not seen any of these benefits. This is due to the technicality of the term “community.” Since the Baka have been resettled from the forests into shoddily constructed villages, they are not considered to be “communities,” but rather “camps,” which do not fall into the category of people receiving benefits from the forest.

In 2017, there was a decision made by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (decision 41 COM 7B.19) stating that the world heritage committee “welcomes the efforts of the States Parties of Cameroon and the Republic of Congo respectively to secure the right of Baka to exploit their resource in areas identified within the property and to promote the sustainable exploitation of fisheries resources, targeting in particular women and Indigenous peoples.”[23] This is progress towards recognizing the Baka's rights, however this decision merely states that it "welcomes the efforts," a phrase that indicates this decision is more of a suggestion than a demand to the governments.

Discrimination and Violence

For thousands of years, the Baka have been kept as slaves by the Bantu,[21][24] a neighbouring ethnic group who are far less marginalized, and who hold more positions of power in the region. These Baka slaves typically work on plantations or in the forest, doing tasks such as tending Bantu crops or illegally hunting bushmeat for their Bantu owners.[21] Because of their forest lifestyle and their indigenous status, they are considered to be "less than human" by other ethnic groups in the region. Many people of other ethnicities do not wish to hire the Baka as employees because they perceive them as lazy and poor workers.

Since the implementation of conservation laws around the turn of the century, the Baka have begun facing aggression and violence from the conservation officers.[25][26] These abuses have been documented and publicized by an organization called Survival who advocate for the rights of tribal peoples around the globe. Below is a video produced by them where the Baka talk about their experiences with conservation officers.

The Aka People

The Aka are another indigenous "pygmy" group in the TNS region.[27] Like the Baka, they are hunter-gatherers who depend entirely on the forest, however they differ in their language and hunting techniques, and live in the eastern side of the TNS while the Baka have traditionally occupied the west. There is far less information available on the effect of conservation on these people. The reason why the Baka have been the focus in the Congo Basin is unclear.

Interested Outside Stakeholders

These are stakeholders who are interested in the issue and may be key players in decision making, but are not deeply tied to and reliant upon the forest in question. Typically, they do not have ancestral claims to the land.

| Interested Stakeholder | Relevant Objective | Relative Power | Scale of Influence |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Bantu people | To maintain a landscape where they can continue their agricultural livelihood. | Moderate to low | Local to regional |

| Congolaise Industrielles des Bois (CIB) | To harvest timber from the region in a profitable manner. | High | Regional to international |

| Conservation NGOs (WWF, WCS, and IUCN) | To protect the biodiversity of the region. | Moderate to high | Regional to National |

| General public in the international community | To protect their relevant interest (for example, wildlife, natural beauty, human rights, etc.) | Low to moderate | International |

| National and regional government | To manage the land in a way that both invites international support while maximizing revenue generated from the land. | High | National to regional |

| UNESCO | To preserve the natural and cultural heritage of the region. | Moderate | International |

The Bantu People

The Bantu people (sometimes referred to as "Bilo")[21] are a majority ethnic group in the Congo Basin. Their language is spoken by about one third of sub-Saharan Africans.[28] Their main livelihood is a "slash-and-burn" form of agriculture, [29] and they have little reliance on the surrounding forests. Though they migrated to the Congo Basin thousands of years ago,[28] the migration occurred more recently than that of the Baka and Aka people, and therefore have somewhat less of an ancestral connection to the forest and land.

Because they are a majority ethnic group in the region they have more representation within the government, and thus they have more power than the Baka. However they do not have as much power as some of the other interested stakeholders. They are not banded together under a uniform organization that could lobby for policies, and like the Baka, there is no place for them within the colleges of the CBFP.

Congolaise Industrielle des Bois

The Congolese Industrielle des Bois (CIB) is one of the many private logging companies operating in the TNS. It operates in the Republic of the Congo and is the largest industrial logging company in the country.[8] It was acquired by the Singapore-owned company Olam International in 2011.[30] Olam also operates in Cameroon, however it is more focused on agriculture than forestry in this region. CIB holds logging concessions to about 1.3 million hectares of forest in the Republic of the Congo, and helps to manage a total of 2.1 million hectares in the region.[30] It became a member of the CBFP in February 2012[31] and holds a lot of influence in the region.

Conservational Non-governmental Organizations

The international conservational non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that operate in the region are interested stakeholders with a moderate to high level of power. They are stakeholders interested in the region purely for its diverse ecological values and they can be backed by a lot of foreign support and money. The ones listed below were all named as participating stakeholders in the region in a monitoring study conducted by Sayer et al. in 2016.[3]

The World Wildlife Fund

The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) is a Swiss-based international conservation NGO that operates in Cameroon and the Central African Republic (CAR) with the intent to help protect and preserve the natural biodiversity in these regions. They are considered an interested stakeholder with a high level of power.

The WWF are considered an interested stakeholder and not an affected stakeholder because the organization is based out of Switzerland. Even though its members and staff care deeply about the animals, plants, and other wild organisms living there, ultimately their livelihood does not solely depend on this particular jungle. If these forests were destroyed, they would still be able to go home and feed their families. They are simply not deeply tied to the land in the TNS. Though the WWF does not have any rights to the land or direct control over the management, their high level of power comes from the fact that they have a lot of influence over the governments in the region. When they began lobbying to protect the biodiversity in the Congo Basin, the governments listened and created the TNS.

Author's note: This page does not differentiate between the different international chapters of the WWF. It does not distinguish between the different interests, values, and power that the chapters may hold.

The Wildlife Conservation Society

The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) is a New York-based international conservation NGO founded in 1895 that operates in the Republic of the Congo in the Congo Basin. Here, its goal is to protect the biodiversity in the rainforests of the Congo Basin.[32] They are considered an interested stakeholder for the same reasons as the WWF. They appear to have less power in the region than the WWF since the formation of the TNS was mostly the work of the WWF.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature

Though the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) does not have any projects of its own in the TNS, it has partnered with many of the stakeholders operating in the region to help provide accurate data on the status of species. The IUCN has little to no power in making decisions themselves, however they do provide science-based evidence to help inform the decisions that are made by other stakeholders. They are not a member of the CBFP, however they were named as a participating stakeholder in the monitoring program conducted by Sayer et al. in 2016.[3]

General Public in the International Community

These are people of the general public in the international community who have a personal interest in the region. They can fall into the categories of tourists, environmental advocates, human rights activists, or others. These interested stakeholders are important because they exert pressures on stakeholders with power to make decisions that benefit their concerns. An example of this is the international support that environmentalists around the globe gave to the WWF when it was lobbying for the formation of the TNS.

National and Regional Government

In community forestry case studies around the globe, government from national to local levels are typically interested stakeholders with high levels of power. In many countries, especially those that have been colonized by European countries in the past, governments hold the most secure tenure over forested lands. Meaning, they are the stakeholders with the most power, who have ultimate control over what decisions are made.

National Ministries

The Ministry of Forests and Wildlife (MINFOF) in Cameroon,[9] The Ministry for Waters, Forests, Hunting and Fishing (MEFCP) in the Central African Republic,[10] and the Ministry of Forest Economy, Sustainable Development, and Environment (MEFDDE) in the Republic of Congo[11][12] are the national government bodies in charge of managing the state forests and the forestry sectors in their respective countries.[10][9][11][12] They are interested stakeholders that hold the highest level of power in the TNS because they have the ultimate control over land management decisions that are made in the region. Among other things, they control who receives forest licenses and what type of licenses are issued. In Cameroon, the MINFOF has control over enforcement of anti-poaching laws under the wildlife law, including organizing patrols and prosecuting offenders.[33]

Central African Forest Commission

The Central African Forest Commission (COMIFAC) is an international Central African intergovernmental organization, whose mission is to integrate conservation and sustainability into forestry practices in Central Africa.[34] It was founded in 1999[35] and includes members from ten Central African countries. COMIFAC adopted a multi-phased "Subregional Convergence Plan" in February 2005[36][37] that details how it will accomplish its mission. This plan includes initiatives such as incorporating environmental policies into forest management and combating climate change, however the closest it comes incorporating local people is the statement of "socio-economic development" as one of its "priority axes of intervention."[35] It is an interested stakeholder with a lot of power, since it operates at an international governmental level and is a key stakeholder in the CBFP.[17]

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) is a United Nations agency that, among many other projects around the globe, is working to preserve the natural and cultural heritage in the Congo Basin. Because the TNS was designated as a World Heritage site in 2012,[2] they are considered an interested stakeholder with a moderate level of power. UNESCO is considered interested for the same reason that the international conservation NGOs are interested instead of affected stakeholders: they are based somewhere else and are not entirely dependent on that specific portion of land.

Their moderate level of power comes from the fact that UNESCO is able to work directly with the TNS land managers to create management plans, due to the TNS being a World Heritage site.[38] The managers (the governmental ministries MINFOF, MEFCP, and MEFDDE) still maintain ultimate control over the decisions that are made, meaning that UNESCO has a relatively moderate level of power.

Discussion of Critical Issues

Conflict between the WWF and the Baka People

The WWF states that they are making efforts to help out the local communities in the Congo Basin,[39] stating that sustainable forest management includes "respect for the rights of local and indigenous peoples."[39] They claim that they are "support[ing] and train[ing] local communities to improve their livelihoods by taking control of managing their forests and natural resources."[39] However, in interviews the Baka say that the WWF has done nothing to help them out.[25] Furthermore, the WWF helps to fund some of the conservation officers and anti-poaching squads who are inflicting unprovoked violences upon the Baka.[40] This has caused the international tribal people's rights advocacy group Survival to file a complaint against the WWF for human rights violations in the Congo.[41][42] This complaint is being looked into by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD.)[42]

Physical Exclusion of the Baka People from the Sangha Trinational Landscape

The formation of the Sangha Trinational has caused the Baka to lose their traditional lifestyle. They are no longer allowed to live their lives the way they have historically due to the ban on hunting. Not only are they no longer allowed to hunt the way they used to, they are afraid to merely be in the forest out of fear that they will be mistaken for a poacher and beaten.[26] Since the TNS is a World Heritage site, and the goal of a World Heritage site is to preserve not only natural heritages but also cultural legacies,[2] it is interesting that UNESCO has not done more to allow the Baka people to continue their traditional way of life. For time immemorial, the Baka have been living in the Congo Basin, contributing to the jungle's ecology. In addition to the harm it is causing the Baka people,[20] removing them from this system seems counterintuitive to the goals of a World Heritage site.

Relative Stakeholder Power Analysis

| Relative level of power | Low interest (interested stakeholders) | High interest (affected stakeholders) |

|---|---|---|

| High power |

|

|

| Moderate power |

|

|

| Low power |

|

|

Recommendations

For the People of the Region

The non-Baka people of the region could significantly help the Baka peoples' situation by working to rid the common mindset of the Baka being "less than human."[20] As long as this perception of the Baka exists, the issues that they face will prevail. Until the conservation officers and non-Baka villagers can see them as equal human beings, they will continue to face discrimination, violence, and enslavement from their neighbours. This shift in perception could be achieved through implementing local programs where Baka and non-Baka children are allowed to interact with each other, free from the preconceived notions that one is superior to the other.

For the Government of the Region

The governments of the regions, specifically the ministries of MINFOF, MEFCP, and MEFFDE, could significantly help to improve the Baka peoples’ situation by incorporating the Baka into their forest patrol, such as what was done in West Bengal.[43] The governments could also amend the forestry law to give benefits to all local people adjacent to the forests, not just "communities,"[14] a term that often excludes the Baka since their temporary villages are often considered "camps." The Jozani forest in Zanzibar has shown that this can be an effective way of supporting the local communities.[44] They could also attempt to write in a section that exempts the Baka from the strict anti-poaching laws. This would allow the Baka to continue living in the way that they have been for thousands of years. Their lifestyle is very sustainable because their animistic beliefs ensure that they treat the forest with great respect. Additionally, the ministries could train their conservation officers to enforce anti-poaching laws in a humane manner. They could partner with the international conservation NGOs, who already help fund the anti-poaching squads, to form training programs that teach how to enforce laws without inflicting human rights violations.

For the NGOs

The International conservation NGOs could significantly help to improve the Baka peoples' situation by incorporating the Baka into their forest protection program plans, similar to what was done with the forest patrols of West Bengal in India,[43] and by putting more effort into ensuring that the conservation officers will treat the Baka people more humanely. Though the NGOs may not have as much management power as the national governments in the region, they could include the Baka in their management plans that they propose to the governments. They could also lobby for the inclusion of Baka into forest patrols. Additionally, by putting more resources into training programs for the conservation officers, the NGOs could help to form forest patrols who know how to enforce the anti-poaching laws without resorting to violence and terror, and who treat the Baka like people instead of pests. Since the NGOs, especially the WWF, are helping to fund the forest patrols, they could refuse to lend assistance to patrols who are not held to a high standard for humane actions. This would force the governments to ensure their officers are not conducting human rights violations, for fear that they would lose funding and support.

List of Acronyms

- CAR: Central African Republic

- CARPE: Central Africa Regional Program for the Environment

- CBFP: Congo Basin Forest Partnership

- CIB: Congolaise Industrielle des Bois

- COMIFAC: Commission des Forêts d’Afrique Centrale (Central African Forest Commission)

- JFM: Joint forest management

- IUCN: International Union for Conservation of Nature

- MEFCP: Ministry of Waters, Forests, Hunting and Fishing

- MEFDDE: Ministry of Forest Economy, Sustainable Development, and Environment

- MINFOF: Ministère des Fôrets et de la Faune (Ministry of Forests and Wildlife)

- NGO: Non-governmental organization

- NTFP: Non-timber forest product

- OECD: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

- TNS: Sangha Tri-National Landscape

- UNESCO: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

- WCS: Wildlife Conservation Society

- WWF: World Wildlife Fund

Author's Note About the Page

This case study is far more complex and intricate than what this page was able to capture. It was attempted to note missed nuances, however many were lost altogether. Though this page can be used to find relevant literature on the topic, it should not be cited as supporting evidence. Lastly, I would like to acknowledge that this case study was written by an uninvited guest on the Musqueam's traditional, ancestral, and unneeded territory.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Historical Background of the Sangha Tri-National (TNS)". Foundation pour le Tri-National de la Sangha. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 "Sangha Trinational". UNESCO. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Sayer, Jeffrey; Endamana, D.; Boedhihartono, A.K.; Ruiz-Perez, M.; Breuer, T. (2016). "Learning from Change in the Sangha Tri-National Landscape" (PDF). International Forestry Review. 18: 130–139.

- ↑ "Human Development Indices and Indicators: 2018 Statistical Update" (PDF). HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ↑ "Welcome to Dzanga-Sangha!". Dzanga-Sangha National Park. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "The Congo Basin and its Forest Ecosystems". Congo Basin Forest Partnership. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- ↑ Maisels, F.; Strindberg, S.; Breuer, T.; Greer, D.; Jeffery, K.; Stokes, E. (2018). "Western Lowland Gorilla". IUCN. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Community Forest Tenure Mapping in Central Africa: The Republic of Congo case study" (PDF). The Rainforest Foundation UK. 2009.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "Ministry of Forests and Wildlife (Cameroon)". the REDD desk. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "Central African Republic Country Environmental Analysis: Environmental Management for Sustainable Growth" (PDF). World Bank. November 2010.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 "Forest Legality Initiative: Republic of Congo". World Resource Institute. January 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 "United Nations Development Programme: Republic of Congo" (PDF). the Global Environment Facility. April 2017. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ↑ "Forest Legality Initiative: Cameroon". World Resources Institute. July 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 "Forest Management Transparency, Governance and the Law: Case Studies from the Congo Basin" (PDF). Rainforest UK. October 2003. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Cooperation Framework for Members of the Congo Basin Forest Partnership". Congo Basin Forest Partnership. November 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ↑ "The Congo Basin Forest Partnership". Congo Basin Forest Partnership. 19 November 2018.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "Members / Colleges". Congo Basin Forest Partnership. 19 November 2018.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "How to Become Member of the CBFP?". Congo Basin Forest Partnership. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ↑ "The Baka Tribe: Spirits". My African Tribe. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Raffaele, Paul (December 2008). "The Pygmies' Plight". the Smithsonian. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Schulman, Susan (4 May 2016). "Life for the Baka Pygmies of Central African Republic". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Southeast Cameroon". Survival. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ↑ "Decision : 41 COM 7B.19 Sangha Trinational (Cameron / Central African Republic / Congo) (N 1380rev)". UNESCO. 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ↑ Boedhihartono, Agni Klintuni; Endamana, Dominique; Ruiz-Perez, Manuel; Sayer, Jeffrey (May 2015). "Landscape scenarios visualized by Baka and Aka Pygmies in the Congo Basin". International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology. 22: 279–291.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "The "Pygmies"". Survival. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "Congo Republic: Baka "Pygmies" beaten up and arrested". Survival. 8 March 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ↑ "Aka". Every Culture. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Patin, Etienne; Lopez, Marie; Grollemund, Rebecca; Verdu, Paul; Harmant, Christine; Quach, Hélène; et al. (5 May 2015). "Dispersals and Genetic Adaptation of Bantu-speaking Populations in Africa and North America". Science. 356: 543–546.

- ↑ Njounan Tegomo, Olivier; Defo, Louis; Usongo, Leonard (March 2012). "Mapping of Resource Use Area by the Baka Pygmies Inside and Around Boumba-Bee National Park in Southeast Cameroon, with Special Reference to Baka's Customary Rights" (PDF). African Study Monographs. 43: 45–59 – via JAIRO.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "Republic of Congo". Olam International.

- ↑ "Welcome to our new partner, "Congolaise Industrielle des Bois (CIB) of Olam International!"". Congo Basin Forest Partnership. February 2012.

- ↑ "WCS Congo". WCS. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ↑ Christopher, Sone Nkoke; Aimé, Nya Fotseu; Bernard, Ononino Alain (January 2018). "Guide to Wildlife Law Enforcement, Cameroon" (PDF). Traffic. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ↑ "Missions de la COMIFAC". COMIFAC. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "COMIFAC - the Central African Forests Commission". Congo Basin Forest Partnership. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ↑ "Plan de Convergence". COMIFAC. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ↑ "Etats Membres". Wayback Machine. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ↑ Frank, Laura; Vujicic-Lugassy, Vesna. "Managing Natural World Heritage". UNESCO. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 "Sustainable Forest Management". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- ↑ "Hunters or poachers? Survival, the Baka and WWF". Survival. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ↑ "Specific Instance" (PDF). Survival. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Barkham, Patrick (5 January 2017). "Human Rights Abuses Complaint Against WWF to be Examined by OECD". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Banerjee, Ajit (2007). "Joint Forest Management in West Bengal". Forests, people and power: the political ecology of reform in South Asia. London, UK: Earthscan Publications Ltd. pp. 221–239.

- ↑ Menzies, N. K. (2007). "Jozani Forest, Ngezi Forest, and Misali Islands, Zanzibar". Our Forest, Your Ecosystem, Their Timber: Communities, Conservation, and the State in Community-based Forest Management. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 30–49.

| This conservation resource was created by Alana Gonczar. It is shared under a CC-BY 4.0 International License. |