Course:ANTH302A/2020/South India

Introduction

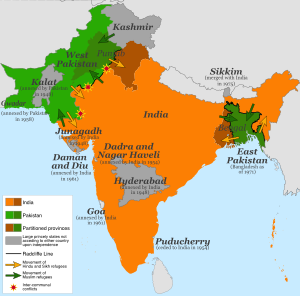

The region of South India consists of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Andaman and Nicobar Islands. In January 2020, India’s first case of COVID-19 was found in the southwestern state of Kerala. Upon arrival of this threat, local authorities worked to confront the disease by imposing a lockdown, enforcing bans on large gatherings, and by advising citizens to withhold from visiting places of worship and social activity. Currently, South India accounts for over forty-percent of India’s active COVID-19 cases, with Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, and Karnataka in the top four most affected states in India[2][3]. The unprecedented nature of the pandemic has transformed the region, posing numerous uncertainties in the future for the social, political, and economic sectors in the region.

On this page, we attempt to cover specific highlights of the pandemic’s impact on South India across a wide range of topics, namely, tourism, healthcare, economy, agriculture, religious tensions, casteism, gender issues, and slum cultures. The pandemic and the subsequent lockdown provide an opportunity to reflect on the larger scope of recovery- reform. Therefore, we present an attempt to cover the many designs of identity that inform one’s place in society. Darius Dharsi offers a perspective into the impact of COVID-19 on the economy of South India and its low-income communities. Maham Keshvani explores deeper into the impact of health declines on prospects of tourism in South India by looking closely at the health conditions and remedies in the regions of Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu. Aarushi Gupta has discussed the pandemic’s impact on agriculture, farm laborers and farmers in South India. She uncovers the new work roles/identities that shaped as a result of an adaptation to challenging times. The detrimental economic impact of the pandemic on agriculture, encouraged innovation into new initiatives to mitigate the harm caused. Ruochen Qin demonstrates the extreme vulnerability of the urban poor residing in slums. He argues that slums create a space of intersection between poverty and social setbacks introduced by the lockdown (like the lack of employment, infrastructure, space, access to public services and masks) further add to their precarious situation. Aman Badhan shows how past religious tensions are brought to light through COVID-19; his section specifically focuses on Islamophobic discrimination in India. Meghna Vijai examines the effect one’s caste has on how they navigate the pandemic. In contrast to the model status ascribed to the region, the social realities of caste-based violence and structural discrimination embedded in South India work in tandem to create a uniquely precarious situation for low-caste citizens. Finally, Shay Li discusses the ongoing gender issues and inequalities in the region focusing on the pandemics specific impact on women based while also addressing the insufficiencies in the governments current plans for recovery in the women's context. This page creates a space to reflect on the importance of social identity and how experiences during the pandemic are situated in long-standing and multidimensional socio-political contexts. The information here can be applied in informing future responses to crises in the region in order to develop more suitable relief models.

Impact on the Economy and Low Income Communities - Darius Dharsi

Background

In any discussion regarding the negative consequences of the coronavirus crisis on the Indian economy, one must also consider how these negative economic consequences have affected the most vulnerable members of society. In this case, low-income groups and those living in poverty, especially Dalits, who also face discrimination and prejudice which worsens their suffering. Folmar, Cameron, and Pariyar discussed the need for South Asian anthropological research to be inclusive and to consider social justice, by also including Dalit narratives into the discussion[4]. Research has shown that Dalits are disproportionately affected more than other groups in South Asia when disasters occur and face issues in accessing humanitarian aid and assistance due to caste discrimination[5]. Folmar, Cameron, and Pariyar argue that silence on caste issues in times of crises, and not reporting them, thus reaffirms caste discrimination[4]. Consequently, a discussion on the impact of the coronavirus crisis in South India should also include how low-income groups such as Dalits have been impacted.

The Lockdown and Income Inequality

India recorded the first case of Covid-19 on January 30th 2020, and the virus soon spread to most regions of the country. In response, the Indian Government imposed a nationwide lockdown on March 25th 2020. This consisted of the closure of all non-essential services and businesses, including retail establishments, educational institutions, places of worship, and restrictions on travel and movement to and from India[6]. These actions have since had a significantly negative impact on the Indian economy has a whole. As a result, from the end of May to early June onward the lock-down was gradually lifted in a phased manner but continued in highly affected zones. A United Nations report issued in April 2020 estimated that around 400 million people in India risk falling deeper into poverty in India due to the coronavirus crisis[7]. This is due to the fact the government-imposed lockdown left many people unemployed, particularly low-income labourers and workers. The majority of these workers belong to Adivasi, Dalit, and “backward caste” communities. Thus, are not only at a socio-economic disadvantage but lack adequate representation and are often victims of discrimination[8]. The coronavirus crisis in India has highlighted the pre-existing prevalent inequality in society. The top 10% of the population hold as much wealth as the bottom 70% and the richest 1% has four times the amount of wealth as the bottom 70%[8]. The wealthiest groups in Indian society are almost all exclusively upper caste, and the poorest groups in society are overwhelmingly lower caste. Thus, during the crisis and lockdown, upper caste groups have faired much better than their lower caste counterparts[8].

The Lockdown and the Economy

A study by the Indian School of Business has found that south India will face less disruption from the Covid-19 lockdown in comparison to the rest of the country[9]. The reason for this is because technology companies, many of which operate in cities such as Hyderabad and Bangalore, are better equipped to deal with the lockdown as they can accommodate working from home and online work[9]. Nevertheless, other regions such as the state of Kerala, where tourism contributes around 10% of the state economy, is facing a looming “economic crisis” according to some economists[10]. The lockdown alone in the Keralan district of Arippa, pushed more than 200 Dalit families into extreme poverty and hardship. As these families lack ration cards and official documents, they were unable to access government support, and travel restrictions meant they were unable to stock up on supplies[11]. Indian organizations such as the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) and the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI) have stated that Kerala will face difficulties in reviving its economy. Although Kerala could consider reopening its tourism sector, experts warn this would worsen the coronavirus situation in the state and pose a significant health risk. Around 20% of the state’s population works abroad, mainly in the Persian Gulf nations, and the remittances they send back to Kerala account for one-third of the state’s economy[10]. The Covid-19 crisis has resulted in many of these expats having to return home, which has both resulted in a rise in the infection rate in Kerala, and a decrease in foreign remittances which has moreover negatively impacted the economy[10].

Impact on Poor Communities

In South India, the virus has particularly effected poorer agricultural communities, as well as low income menial workers. Out of the top 20 districts with the highest active Covid-19 cases in India, 8 are in Andhra Pradesh (as of 7th August 2020), all but one being rural districts, making Andhra Pradesh the third most affected state in India[12]. District officials attribute the spike in cases their migrant workers returning home and fisherman arriving from Tamil Nadu[12]. The lockdown period in India also saw an increase in violence against Dalits and low caste groups. During the lockdown period in Tamil Nadu, there were at least 81 cases of atrocities against Dalits and tribal people[13]. Other examples include a Dalit youth who died in police custody in Prakasam, Andhra Pradesh in July 2020. He had been arrested for allegedly not wearing a mask while riding a motorcycle[14]. Despite the hardships and suffering experienced by many during this crisis, regional governments such as the government of Andhra Pradesh did try to help low income communities by providing financial assistance to families living below the poverty line. In April 2020, the Andhra Pradesh government decided to provide 1000 rupees each to 13 million families that were living below the poverty line[15].

South-India and COVID-19: Health and Tourism: a Regional Change - Maham Keshvani

Background:

A distinct culture, renowned landmarks, and indulgences of foods all account for why South India interests many incoming tourists. South Indian culture exemplifies a celebratory way of life through art, music, and distinct architecture. South Indian territories and cities such as Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu contain some of the most well-regarded historical landmarks, which makes the South Indian region a popular destination for travel. Regrettably, present-day conditions funded by the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has triggered an unprecedented crisis in the tourism industry, given the current state of health insecurities. A decline in regional health prospects has led to implementing health measures that aim to employ social distancing procedures to minimize unnecessary associations between individuals. The outbreak of COVID-19 has brought many sectors of daily life to a cessation; however, the tourism industry faces great adversity as the uncertainty of contracting illness leaves tourism prospects in remission. Though unfortunate, it is evident that increased health risks have slowed tourism amid the pandemic and is likely to post-pandemic.

Health Deficiencies Overview:

The pandemic has posed a significant degree of threat to individuals worldwide. However, locations that exhibit barriers in the development of infrastructure and care facilities and barriers to attaining resources are hit by the effects of the pandemic to a greater degree. South India encompasses areas that are both developed and underdeveloped; however, both are struck by the consequences of declining health prospects due to the pandemic. In South India, amid the “vulnerable age of airborne viral disease,”[16] many citizens are facing life-threatening sickness and, in more severe cases, mortality. The South-Indian state of “Kerala became the first Indian state to diagnose a patient with Covid-19,”[16] and since then, cases rapidly upsurge in high quantity. Due to the lack of regulation to contain the disease, and the worsening conditions, many individuals already susceptible to illnesses such as “tuberculosis, hypertension, diabetes, mellitus, cardiovascular diseases and sickle cell anemia face a further threat which increases their vulnerability towards COVID-19” [17].

Additionally, the South-Indian public health care system faces serious concern regarding the efficacy of their public health policy. These policies consist of the “assessment and monitoring of health, the formulation of public policies designed to solve identified local and national health problems, and access to appropriate and cost-effective care”[18]. The health system is falling behind in providing citizens with aid in these three vital areas, which poses a significant threat to current citizens and incoming tourists. An ineffective agenda towards implementing such policies and health care solutions would potentially put tourist activity on hold due to the uncertainty of contracting or effectively containing the illness.

In Kerala, Doctors continue to educate patients in hospitals on the “connections between individual illnesses and collective changes, including polluted water, unsafe food, and corrupt pharmaceutical institutions”[16] . Moreover, Dr. Jacob Vadakkanchery, a health activist and chairperson in a hospital in Kerala, asserts the usefulness of “nature cure therapies for corona, and that we must trust in nature”[16]. Correspondingly, in locations such as Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, “Indigenous communities assert the value of environmental practices and medicinal systems to protect themselves from diseases”[17]. The health practices of a ‘nature-cure’ outlook adopted in the South-Indian region are far from being a remedy to the disease. Such proclaimed cures can not be mandated as a remedy to the disease and therefore open up the social sector for travel, tourism, and socialization.

Health Impact on Tourism:

The invasive nature of health decline has indefinitely pronounced an regional change in the tourism sector despite initiatives to promote nature-based medicine as a possible cure. The increased threat due to the airborne spread of germs has resulted in the “suspension of surface transport and domestic and international air travel, closure of hotels and restaurants, and thousands of places of worship” [19] Tourist attractions have been brought to a stand-still the tourism industry is facing a complete shutdown. The usual, “every day thought, horizons and expectations has been gradually transformed”[20]. It is no longer as easy as booking a flight, flying over, and checking off the historical monument that was just photographed off the bucket list. This airborne illness and the incapacity to adequately manage the effects have transformed tourism prospects for the South Indian region for the long term.

Some of the most well-known landmarks in the South Indian region visited by tourists include the Charminar Mosque in Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, the building depicting the era of the British rule in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, and Alleppey Backwater Hot Spot in Kerala. These locations are the most frequented and take a spot at the top of the list of historical and scenic attractions in South India. In the case of Tamil Nadu, “a tourism department official stated that with the pandemic causing havoc globally, it would be unwise to open up the tourism sector in Tamil Nadu immediately”[19] . Furthermore, South-Indian officials state that “rebooting tourism initiatives will be challenging because the lockdown has substantially weakened the financial health of tourism and its allied activities”[19]. Many corresponding vendors that welcome tourists will also be slow in starting up again due to the degree of vulnerability that exists. We can see that “hotels are vacant, so there are fewer ‘security points ‘to manage pandemic conditions at each one because there are no guests”[21]. And additionally, by the time such precautionary measures are imposed and “after the infrastructure is accommodated to better suit the nature of the pandemic, tourists will be slow to return”[21]. These circumstances collectively imply a delay in the reopening of the tourism sector and suggest that only minimalistic touring options will be sanctioned once restrictions are loosened. The “revival of the tourism sector would be dependent on government officials” [19]; however, it seems unlikely that there would be much progress amid the pandemic, or immediately post-pandemic.

Future Recoomendations and Projections for Tourism:

In the South Indian region, due to deficiencies in the public health care system and lack of access to aid, it seems that projections of unrestricted tourism are far from being accomplished. South Indian officials must strive to attain pandemic disaster relief immediately to come to the aid of the region. If the region is unable to facilitate immediate aid to contain the illness themselves, “given the worldwide profile of the pandemic, it became essential for agencies with ambitions in the disaster arena to become involved” [22] in order to provide resources for rehabilitation. The involvement of members from the Disasters Emergency Committee such as, “World Vision, Oxfam, CARE, Concern, Save the Children and the British Red Cross,”[22] would be essential to provide enhanced care resources to rebuild the public health care system that well-suits South Indian residents. In the projected future, we can hope for an outcome that entails a well suited and efficient health care system, robust health care policies and optimistic visions South India to restructure the health care system for citizens and regenerate prospects for uncompromised tourism. Though there remains a prolonged period for these changes to transpire, South India is on its way to remedying the difficulties associated with the precarious nature of the pandemic.

Aarushi-Horticulture and impact on farmers

Introduction to farmers' financial struggles

The COVID-19 based lockdown in India terminated all commercial and recreational activities, while exempting agricultural practices. Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister, Jagan Reddy, allowed farmers to harvest their crops after a year's hard work[23]. In order to harvest crops, the farms required daily wage laborers. However, many migrant farm laborers returned to their hometowns during the lockdown. The lack of transport facility to lift laborers from villages posed a problem to gather workers [24]. Consequently, the laborers who stayed close to the farms demanded higher wages, creating difficulties for farmers to hire workers. Moreover, farmers were burdened with the shut-down of agricultural markets in the cities, eliminating their immediate after-sale income. After the shut-down, farmers were forced to store their produce for future sale. The absence of cold storage units to store perishable crops, aggravated the issue of waste and income loss[25]. The possibility of spoilage, uncertain income, and demands for a wage rise, put farmers in a very difficult financial situation during the pandemic.

Farmers' survival response to the crisis

In this situation, many farmers came up with survival tactics to uplift themselves. The farmers’ initiatives can be compared to Aijazi’s idea of survival. He reveals ‘the “ordinariness” of survival—which is rarely achieved through some grand transcendent gesture' [26].Through this quote, the writer describes the everyday life of Pakistan's earthquake survivors, which is ordinary in that it constitutes regular activities, but magical, as it embodies the spirit of survival. Chandni Bibi, who lost her vision after the earthquake, goes on to live her life and performs regular tasks such as spending time with her brother's children, visiting her Chachi (relative), resting on the bed, and praying[27]. Even though a routine emerged out of her post-disaster life, it is significantly different from her life before the earthquake. Earlier, she would cook, make tea, sweep the floor, clean up rocks from the fields, and plough the ground [28]. After losing vision post the earthquake, she was unable to carry on with these tasks, but established a different routine instead. Chandni Bibi's survival, as demonstrated in her everyday resilience by finding alternate occupations, reflects the ordinariness yet remarkability of post-disaster emergence.

In the case of COVID-19's impact on the sale of agricultural products in South India, some farmers have found alternate arrangements to survive, despite the extraordinary circumstances. A farmer who sells grapes on the outskirts of Bangalore, used Facebook as a Social media marketplace, to advertise his unsold produce [29]. On receiving a positive response, he rented a van and drove to the city to sell his grapes. In normal circumstances, he would sell his fruits to a trader. The trader would sell to wholesalers/retailers, who in turn, would sell to customers. Now, he directly sold to the customers, eliminating margins earned by middlemen, thereby increasing his income. He also received the cash as soon as he sold his produce, as opposed to receiving it from traders two months after the sale. He plans to sell his produce directly even after the pandemic ends. The farmer's survival instinct pushed him to take reasonable, ordinary steps that proved fruitful.

Dalit farmers' neglected experiences

However, the above- mentioned story is a rare example of survival through ordinary practices. The interpretation of ‘ordinary’ also differs across farmers of various classes, castes, religions and genders. For rural Dalit farmers who lack access to basic transport vehicles such as vans, the income to purchase fuel, and the technical know-how of utilizing Facebook as a Social media marketplace, it isn’t ordinary to reach cities to sell their produce. It’s surprising to see the absence of media coverage on rural Dalit farmers’ survival and adaptation to the pandemic in South India. The low status location of Dalits in the social hierarchy, coupled with their geographical dwellings in remote, underdeveloped, rural areas points to the evaluation of their anthropological locations. In the article, ‘Dots on the Map: Anthropological Locations and Responses to Nepal’s Earthquakes’ Professor Sara highlights the possibility of a reduced interest in learning about the earthquake experiences of the Dolakha region as compared to Namche bazaar[30]. The reason being- ‘Namche is the heart of the Sherpa-run trekking industry, the place from which Everest expeditions take off, while northwest Dolakha is home to the marginalized Thangmi community, with very little tourist or other infrastructure’[31]. Professor Sara feared that the ‘densely populated, culturally rich terrain of Dolakha’, would be diminished to a ‘remote forest’ due to its inaccessibility, and the region’s experiences of the earthquake would be dismissed[32]. In the case of rural Dalit farmers, a similar reasoning can be employed, as very little to no media coverage has documented their pandemic experiences. The Dalit community’s socio-economic location and geographic inaccessibility has lessened overall interest in understanding their struggles. Furthermore, Dalit rights bodies claim that no relief plan has been designed to impart ‘medical supplies, social security, and livelihood support’ to Dalit farmers[33].

Government's role in alleviating COVID-19's impact on the Horticulture industry and farmers

Besides Dalit farmers, many other farmers received no financial support. Sushil Parekh, CFO at INI farms, estimates farmers’ losses to range from 30% to 80% depending on the product and location of farms across South India[34]. INI farms, a horticulture start-up that spans Andhra Pradesh and Tamilnadu, works with farmers to cultivate and export pomegranates and bananas to over 35 countries[35]. The lockdown was a hard-hit for their peak export season that runs through January to May. As exports contributed to 85% of their revenue, supply chain disruptions such as the termination of air cargo, shortage of truck drivers, and port stoppages reduced their business to 50% of operational capacity[36]. Only after government intervention, through granting permissions to supply essential packaging and transport services, supply chain disruptions were eased. As witnessed in INI farms' case, the government’s role in managing any disaster is crucial and can greatly alleviate suffering. However, in many instances, Klein’s disaster capitalism, or the ‘introduction of doctrines after a population has suffered the shock of an invasion or a natural disaster’ has been witnessed[37]. Disaster capitalism refers to the implementation neo-liberal policies that benefit corporations while potentially harming marginalized groups[38]. In the state of a natural disaster, people are emotionally vulnerable, often struggling to adapt to the after-math of a shock. People are willing to trust policymakers and accept new, bold measures designed by the government. Many governments misuse this situation to enact controversial laws that would normally face opposition. People then view the enactment of these laws as necessary action or overlook its consequences in the light of a disaster.

In Andhra Pradesh’s case, the government has taken special steps to support local farmers and women during the pandemic, contrary to engaging in disaster capitalist practices. The government has procured bananas from farmers with high-yields and is selling the fruits to consumers via women self-help groups[39]. (Women self-help groups are formed by women who wish to improve their living conditions by pooling money and offering collateral free loans). The farmers would receive Minimum support price form the sale of their fruits and women would earn a commission on every kilogram of sale[40]. Engagement with women self-help groups to sell perishable fruits is a progressive step to encourage women employment and support farmers who cannot store their produce. The Indian Central Bank, RBI, has issued a moratorium, or the postponement of debt repayments, for a period of three months to support South Indian farmers who rely on credit to grow and harvest their produce[41]. Moreover, the PM-Kisan Yojana has extended Rs.2000 cash transfers to smoothen cash flows for farmers[42]. The Indian Council of Agricultural Research has developed a special agro-advisory community to maintain hygiene and enforce social distancing among farmers working on the fields[43].

Conclusion

Overall, farmers and the Horticulture industry in South India has been majorly impacted by the pandemic. The government has eased restrictions on agricultural practices to support the Horticulture industry. They have also engaged in procurement and sale of perishables, ruled three month moratoriums, extended cash transfers, and enforced social distancing to support South Indian farmers. But, the voices of Dalit farmers continue to remain unheard.

Ruochen-Slum Crisis during the Pandemic

Introduction of Slum crisis and History of Slum Development

On July 30th, Bloomberg published an interview in which Dr. Jayaprakash Muliyil, the chairman of the Scientific Advisory Committee of India’s National Insititute of Epidemiology, estimated that herd immunity may have been achieved in India’s biggest slum located in Mumbai. “If people in Mumbai want a safe place to avoid infection, they should probably go there,” suggested by the India’s leading epidemiologist.[44] Although achieving herd immunity in the slum would definitely save lives in the short term, however, many concerns that it will become another perfect excuse for the Indian government to avoid the historically rooted issue of slums in India.

The harsh life quality of urban poor residing in the city slum, even worse than the one discribed in "Out Here in Kathmandu", had always been a difficult and problematic task for the Indian authorities to tackle[45]. For year, the Indian government failed to allocate enough human power and invest sufficient resources to develop a strategy to completely overhaul the growing impoverishment in these informal urban settlements. Since the implementation of a series of poorly designed government policies, the proportion of urban slum population continued to grow. The 2011 Census conducted by the Indian government estimated 65 million people are slum dwellers, or to express it in more obvious terms: “one in every six household in urban India live in slums”.[46]

Failure of government actions also exist in the states of South India. The passing of Tamil Nadu slum Areas (Improvement & Clearance Act) of 1971, the first legislative action designed by the Tamil Nadu government aimed to protect the right of slum dweller to stay in the slum further accelerated the slum expansion in Tamil Nadu’s major city.[47] Currently, Census indicates that approximately 28.6 percent of residents of Chennai, the Capital city of Tamil Nadu, live in the slum[46]. However, this type of supposed protective Acts failed to provide financial support, employment security and basic infrastructure to support the essential livelihood for the unprivileged community, and they failed to be the cure of this urban crisis plagued Indian society for decades. Dr. Tathagata Chatterji concluded in his research published by the Observer Research Foundation that the area-specific investment of “financial capital (employment generation), physical capital (hygienic living environment), human capital (skill building)” from local authorities are keys against slum expansion and for developing urban sustainability in the Post-pandemic era[46]. Unfortunately, most slum communities rely heavily on the Supports from Non-Government Organizations (NGOs), especially during the period of disaster. The over-reliance on NGOs for disaster reliefs, on the other hand, posed a new set of problems. In brief, the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic imposed a snowballing effect that further exacerbate the harsh living environment inside the slum, and urban slum dwellers will get further entrapped in the cycle of poverty unless adequate legislative policies adopted by the Indian government after the disaster.

Public Health Crisis and Insufficient Infrastructure

In Tamil Nadu,the first positive tested COVID-19 case, a 45-year-old resident, was confirmed on Saturday, March 7th[48]. Like all slum areas in the nation, slums in South Indian states also intended to implement a series of strict public health protocol aimed to limit the spread of the COVID-19 virus. Due to the “person-to-person spreading” nature of this highly infectious diseases, over-populated slum settlements are ideal hotspots for the virus to strive, and outbreak in such area are bound to be disastrous. An article from The Lede claimed that high population density makes health protocol such as physical distancing, one of the most basic and scientifically confirmed method that contains virus spreading, practically impossible[49]. Unlike the middle- and higher-class residents’ living condition, which described in the documentary “I am Gurgaon” as “gated colonies" surrounded by security personnel, in the red-zone, however, statistics revealed that “67 % of the household in slums live in one-room tenements” and almost 40% of dwellers live in “semi-permanent and temporary structures”[49][50]. For the urban poor, enforcing lockdown policy and social distancing order are too luxurious a task to accomplish. The lack of fundamental infrastructures also severely hindered the hygiene condition inside the slums. It is reported that approximately 20% of slum dwellers in Chennai’s red-zone need to travel more than 500 meters to access the stationary water source[49]. Limited water allowance forces the people to balance the trade-off between consumption and hygiene requirements. Officials from the Public Health department advised that shared communal toilets should be frequently cleaned to minimize the risk of virus exposure. However, many people, such as T Amudha from Gandhi Nagar, had pointed out that their community rely on water tanker to supply the water, and there are simply not enough resources to keep the public toilet disinfected[51]. In the post-disaster era, the provincial government need to invest more capitals to develop infrastructure in the slum area to prepare for the potential disease and crisis in the future.

Public Heal Crisis and Economic Hardship

Economic hardship brought by the virus also negatively influenced slum dwells’ ability to follow the health guidance, as a result affected their health disproportionately in comparison to the non-slum residence. Prior to the outbreak, a substantial amount of slum community members are daily wage earners engaged in informal economy[46]. Unlike population occupied the top employment hierarchy, who received proper education and able to work remotely at home, unskilled labor previously worked in small business sector, such as manufacturing sector, suddenly lost all sources of income due to the lockdown policy and fall into a state of acute poverty. For some, surgical masks and food items became luxuries that they can barely afford. In Chennai, researches estimated that 20 percent of resident do not have access to surgical mask or other proper face-wear to protect their respiratory system[49]. Chatterji pointed out in his study that it’s important task for the government to protect the urban informal employment opportunities, since “formal and informal economies are highly intertwined [in India][46]. In the long run, welfares programs that dedicated to rise the standard of living and offer better education to worker in the slum will benefit the society and strengthen India’s economy in general.

Non-Government Organization and Disaster Relief

There are currently more than 100 NGOs, both local and international, in Chennai operate in collaboration aimed raise public safety awareness and distributing essential material supply to fight off the virus. These NGOs focused primarily on historically marginalized community and financially vulnerable population in the red-zone such as female, children, and elderly. Project “Feeding Chennai” initiated by the Acid Survivors & Women Welfare Foundation have provided Hygiene Kits and Food Items to more than 10,000 low-income household residing in Chennai’s urban slum[52]. Members of Sahodaran, a LGBTQ community NGO established in Tamil Nadu, are conducting door-to-door awareness campaign in the slum area. They are convinced that it’s important for the community member to get a better comprehension about the harmful effect of the virus[53]. However, it is unsustainable to rely completely on NGOs to conduct disaster reliefs in a post disaster environment, especially during a global pandemic, which international organizations have to distribute their assistance on epicenters around the world. The “Feeding Chennai” project only raised 29,000 Rs from 3 supporters in a recent online fundraiser, just enough to support 58 households, way behind the original goal 2,500,000 Rs[54]. More importantly, like Stirrat explained in “Competitive Humanitarianism: Relief and the Tsunami in Sri Lanka”, NGOs often focused on media attention and publicly “carving out territories” that the welfare and needs of the under-privileged are not their primary concerns[55]. Stirrat concluded that foreign-based NGOs need to “get rid of [the money] in the ‘right way which would fit with Western donors’ visions of what relief should be”[55]. Although, such large scaled scandals during the pandemic haven’t been reported by South Indian media, but one can expect disregarding of people’s need is happening, at least at some level, due to the nature of NGO’s operation model.

Aman-Minority and religious discrimination

History of Religious tension

Religious conflict within India has always been an enormous problem throughout the country's historical past, within these conflicts, minority groups are discriminated against and oppressed. For example, the partition. In the partition, violent actions and anti-Hindu, and anti-Muslim narratives incited people to take arms against each other, which profoundly affected the country's people to hate each other[56]. This can be seen when India and Pakistan separated, and both governments used anti narratives to suppress the minority groups to protect their own national identity. This action was done by the two governments by inciting hatred within the countries, which exacerbated the problem because, before the partition, different religions coexisted with each other relatively peacefully[56].This historical event shows how deep-rooted religious tension has always existed within the country, as well as, how tensions are formed. In Urvashi "Voices from the partition",she explains how when she was young she had thought tensions between Hindu's and Muslim's were not there anymore[57]. However, She had realized when she was collecting stories on a documentary about the partition that she was working on, that this was not the case, deep-rooted tension exist within India even after the partition. Here is the quote that explains this aspect. "Nothing as cruel and bloody had happened in my own family so far as I knew, but I began to realize that Partition was not, even in my family, a closed chapter of history—that its simple, brutal political geography infused and divided us still"[58]. Moreover, in her own family a clear example can be seen where prejudice against the Muslims exist because her family did show a dislike towards the Muslims[59]. Today, Pockets of this underlying tension can be seen resurfacing through COVID in 2020. In this particular section, COVID is being used as an excuse to subjugate minority members.

COVID 19 and the discrimination in Karnataka

Fast forward to 2020, deep-rooted religious tension is still widespread in India today. Recently, the COVID pandemic has sparked religious tension, which fueled many people in India to discriminate against the minority Muslim members and falsely accuse Muslims of spreading the virus on purpose. All over India, Muslims have been discriminated for spreading COVID[60]. However, it is significant to note that not everybody in India participates in discrimination against the Muslims.Muslim discrimination in the pandemic became widespread when the Tablighi Jamaat people tested positive after a large convention in Delhi, had spread the virus unintentionally in their communities when they returned back to their homes[60]. Moreover, a CNN report also stated that,"In total, approximately 200 million Muslims have been targeted and attacked all over India. As previously stated, this resulted in beatings. Many people have also participated in the ridicule, beatings and name-calling the Muslim terrorist"[60] . This section of the wiki will focus on the south of India in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu.

In Karnataka, many incidents occurred against its Muslim citizens throughout the state. In Bagalkot, a village in the south, saw two Muslims being forced to beg for forgiveness because they were wearing their traditional attire. The video also showed the men being beaten by 10-15 people with iron and sticks and told that they were the reason the virus was spreading and that they should not be touched[61]. They even uttered, "You people (Muslims)are the ones who are spreading the disease"[61]. Similarly, In Kadakarappa another village, angry hooligans went into a mosque and attacked the people praying. In the capital city of Karnataka, Muslims distributing food were hit with cricket bats by hooligans. This quote from the quint explains the incident in great detail. "They told us that we are not allowed to distribute food, that we are all from Nizamuddin[61]. They said the virus is spreading because of us and that we cannot distribute the food" [61]. In other parts of Karnataka, like Mangaluru, posters were posted around the area banning Muslim citizens from trading until COVID passed[61]. These events symbolized the divide and how some of its citizens, mostly Hindu's discriminate against Muslim minorities. This example shows clear evidence that religious tension also exists in south India and that some residents do feel strongly about Muslims within their neighborhoods .

COVID 19 and religious discrimination in Tamil Nadu

Before I begin this section, it is important to note that everywhere in India Muslims have been subjected to discrimination. They have also been accused of spreading the disease across India[60]. In the state of Tamli Nadu, this aspect is very prevalent. Lets look at the health care system for example in Tamil Nadu. In the news article, written by Kuntar, " people talk as if COVID came from Melaplalyam and not China", Kuntar explains how the Muslims who travel back from Dehli to Melaplalyam did not receive accurate information of who got the disease from those who traveled back from Delhi. Kuntar also explains how the entire area of where Muslims were, was shut down even though only a few of them had it, out of a population of 300,000 only 32 people had COVID[62]. This obscure number shows clear religious prejudice. Doctors and healthcare areas also did not allow Muslims into their facilities. For example, a Muslim man, name Muhammad, was allowed to enter the health care system before COVID and later died as a result of being denied access to treatment[62].

Concluding thoughts

I think it is important to remember that India has always been a place that is very secular and that the discrimination In India should not be what defines India as a nation[63]. Within South Asian limitality also existed. For example, Gandhi, Gandhi did not categorize himself as being Hindu or Muslim. Instead, he was a believer of many faiths and I think moving forward religion should not be so intertwined with politics, instead people should learn from Gandhi‘s example and respect all religions.This is very important to remember because we do not need to add to the problem COVID has given us.[64].

Meghna Vijai- The Role of Caste in Experiencing the Pandemic

South India is often presented as an ideal region; images natural beauty, high literacy and low poverty rates, and sustainability are conjured. Kerala is now also recognised for its efficiency in combating COVID-19, contributing to the so-called “Kerala model”[66][67][68]. The question remains, when the response to a crisis is based solely on recovery, what exactly is left out of the equation? Is it sufficient to aim for a return to the status quo when for many “normal” may not mean “good”? Studying caste in South India under lockdown conditions presents an opportunity to analyse the normal from the perspective of the abnormal. By all means, the pandemic should have elevated caste pressures. But that is not the case. Caste has become so embedded in the culture that it informs how people experience the pandemic and lockdown. Understanding this equips one to appropriately respond to people’s needs[4].

Direct Caste-based Violence

Periodically society takes notice of the reality of casteism when a sensational article about violence against Dalits is released. Each incident is treated in isolation— like an exceptional case— and soon the public’s fervour passes and the agenda is forgotten. Mid-June 2020 P. Jeyaraj and his son, Bennicks, died due to custodial violence in Sathankulam, Tamil Nadu (TN). They were arrested because Jeyaraj had supposedly left his shop open beyond curfew and Bennicks had tried to defend his father from getting beaten[69]. In reality, the incident was related to an escalating conflict between two castes in the region, the Nadars and the Konars[70]. Ravishankar quotes an eyewitness as saying “There had been violence from the beginning, since these policemen were posted here. But there was too much violence during Corona time”[70] (part 4, para. 5). Both Chief Minister Edappadi K. Palanisami and Minister Kadambur Raju dismissed claims of custodial torture despite abundant evidence[69].

In Chirala, Andhra Pradesh, Yaricharla Kiran Kumar, a Dalit man, was jailed on 18th July for not wearing a mask. He died in custody on the 21st. Again, police denied claims of brutality, maintaining that Kumar voluntarily jumped out a moving vehicle. The government has been criticised for their inaction over continued police violence[14]. On the same day of Kumar’s death Vara Prasad, another Dalit man, was beaten and humiliated by a constable for arguing with a local leader. Nara Lokesh has been quoted asking “Don’t Dalits have a right to live under [Chief Minister] Jagan’s regime?”[71] (para. 10).

Prejudice also manifests in family and kinship. Ambedkar, writing about how the anti-social spirit of caste hierarchy prevents the formation of filial ties beyond one’s caste, states “a caste has no feeling that it is affiliated to other castes”[72] (p. 19). M. Sudhakar of Tiruvannamalai, TN, had married a woman of a higher caste, but fled to Chennai to escape her family. However, forced to return due to financial hardships caused by the lockdown, on March 27 he was beaten to death by his in-laws when he returned[73]. Rani reports seven similar incidents in the state during the lockdown[13]. This highlights the indirect consequences people face during the pandemic. Many who migrated to cities and were employed in the informal sector were forced to return to their villages where they would face similar atrocities[73].

These are just examples in a long history of caste crimes. In fact, Muralidharan writes that caste violence in TN has spiked during the lockdown. Citing A. Kathir, director of Evidence, she writes that the state saw a 40% increase with 25 cases in April[74]. Referring to such cases, Kathir states that since the media is “so obsessed with COVID-19 cases alone, we hardly get to hear about them”[74] (para. 10). Rani reports 81 cases in the state between late-March and early-July[13].

Structural Violence and Reconstruction

It is important to note that casteism is not limited to physical violence; it is also a system of social and psychological oppression. For example, “India Untouched” shows how Dalits across rural South India face discrimination— segregation, forced labour, humiliation, verbal abuse, etc. Stalin demonstrates that regardless of laws or narratives of “development”, caste continues to exist as a major factor of people’s lives[68]. Most cannot justify casteist practices, nevertheless they believe they are integral to their ways of life, their very existence. This suggests an individual’s response to the lockdown would not be isolated. Rather, it would be compartmentalised and situated in pre-existing ideas of being.

Furthermore, Ambedkar writes that the division of labour under caste results in “a hierarchy in which the divisions of labourers are graded one above the other”[72] (p. 17). This has caused a stigma around certain jobs, an extremely harmful consequence evident in the sanitation industry during the pandemic. A survey of sanitation workers in India shows that 95% participants were from Scheduled Castes and 90% did not have health insurance[75][76]. At least 23 workers tested positive in Bengaluru, Karnataka, and workers in the city staged an indefinite protest due to lax safety standards[76]. The permeation of caste into wage labour, health, and safety reaffirms the belief held by both Stalin and Ambedkar that reform can only work when it is shaped by an acknowledgement of social identity.

Folmar, Cameron, and Pariyar discuss the silence around Dalit issues post-disaster perpetuated by the idea that caste concerns should not take precedence over the disaster. They caution against “dismissing common practices of social inequality for a rosier picture focused only on resilience”[4] (para. 9) because a rhetoric like this ignores how social inequality informs how the distribution of aid takes place. Stalin also demonstrates that dismissing caste is to deny people their experiences— “in Kerala, they don’t attack you on the basis of caste. Instead they declare that caste does not operate here”[68] (1:13:14). Applying the analytic framework used by Folmar, Cameron, and Pariyar to the daily experiences of those in “India Untouched” helps circumvent the superimposition of Western ideas of material reconstruction and recovery onto the subjective context of caste-informed life in South India[4]. Post-Covid reconstruction must therefore be one centered around reform. It necessarily requires an inclusive approach that takes into account ongoing discrimination faced by those at the margins of society.

Gender Inequalities and Women's Issues - Shay Li

In present day Southern India many efforts in the labor and political sectors have progressed to empower women to participate actively in economy and society, yet many of the deep-rooted gender inequalities still remain unaddressed. This generation boasting a new reality for Indian women marked by the "sizeable increase of women in the professional workforce" and "a perceived decline in joint family living"[77] arguably still fails to successfully resolve the base of women's issues. The UN has ranked India on the Gender Inequality Index to be below many sub-Saharan African countries, pointing to the persistent gender issues prevalent even though India is a model of extensive economic development and expansion in the recent decade[78]. Although regions of South India have had persistent long-standing issues with gender equality, the global COVID-19 pandemic has caused a ripple effect in the realm of women's issues pointing to many gaps in the system. Arguably, the burden of the pandemic has fallen disproportionately on women as previously present gender issues have only been intensified as an outcome of the extraordinary circumstances. The governments response to the Pandemic aimed at containing the spread of the virus has however greatly ignored the specific struggles of women during this time, preventing true women's empowerment and gender equality.

Structural Violence and Reconstruction

The government's response to the pandemic has insufficiently addressed women's issues as women have "remained largely absent from the governments COVID-19 policy"[79] due to the gaps in policy that fail to encompass women's food, health and income security impacted by the pandemic. From research in the after effects of past Pandemics such as Ebola and Zika virus, a reported increase in "health consequences" ultimately "fall disproportionately on women - as they lost control over sexual and reproductive lives"[79]. In the coming months after the lockdowns it is highly plausible there will be a reported increase in unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases as a result of limited access to contraceptives. Additionally, in the first weeks of the lockdown the government failed to include sanitary pads in the list of essential items[80], forcing women across the nation to struggle with accessibility to basic feminine products and look for alternate solutions. For instance, women in self help groups in South India have began to gather to address the shortage of feminine products by making sanitary pads on their own, as pictured on the right. The fundamental health needs of women have been greatly left out of the current plan for recovery as limitations in the supply chains and challenges to accessibility point to new struggles in the long-run.

Furthermore food insecurity due to the loss of income during the lockdown has had a profound impact on the impoverished populations. Although the Southern regions have reported decreasing rates of poverty[81] based on a UN report in 2010, the "unintended consequences for the poorest" is still a reality in the South [82]. In the event of food scarcity it is shown that women and girls "eat last and least"[83] pointing to a high propensity for an increase in cases of women's malnutrition and health issues.

For the women that are left in the essential workforce, the implications of COVID-19 have drastically increased their vulnerability to such diseases as a 83% of women are reported to be nurses [84]. In comparison to doctors - a widely male dominated occupation- nurses are lower in the hierarchy ultimately resulting in less protective gear and higher chances of contracting the virus.

Another gap in the governments response to the Pandemic points to the lack of resources to alleviate the compounding pressures of mental health issues as a result. Women are naturally disposed to have higher rates of depressive disorders at 41.9% in comparison to 29.3% in men [85] suggesting women under the pressures of lockdown could become more susceptible to mental health issues. However the limited resources for women coupled with the fact that only 29% of women have access to the Internet in India presents a scary truth on the state of mental health[86]. Limited accessibility and information across South India on the health aspects of the Pandemic beyond the COVID-19 virus ultimately creates a gap in necessary services to address many underlining women's issues. The psychological dimensions of the Pandemic can not be ignored as mental health issues point to the oppression of women that is widely invisible. By failing to address and acknowledge the propensity of higher levels of mental health issues on the rise it essentially silences the struggle of women and men alike during such uncertain times.

Gender Violence in Lockdown

Following the development of the COVID-19 Pandemic in India, the nation mandated lockdowns through an announcement on March 23 resulting in an immediate absence of wages, work and relief marking the beginning of the domino effect[87]. Many social issues have risen in the domestic sector pointing to a very plausible rise in gender inequality and gender violence due to the stressors of lockdown and economic hardships. Arguably the structure of home-life in India already places many pressures on women to take care of family matters including child caring, cooking, cleaning and other forms of unpaid informal labor based on deep-rooted gender expectations. In South India the "kinship rules rooted in cultures and gender norms that categorizes human social life"[88] ultimately limit women's social mobility and freedom to the confines of home life fostering a culture of subordination. The increase in time spent at home has inevitably increased the domestic workload, which is a burden disproportionately placed on to women creating a "clear gender dimension" [85] to the Pandemic. Furthermore, domestic violence has been a withstanding issue in India and is now only further aggravated by the increased hours spent confined in the home due to the circumstances of the lockdowns.

Take in to consideration the South-western region of Kerela which has reported consistently increasing statistics of sexual violence and rape on women withstanding the fact that it is the most literate region in India [89]. Although the state of Kerela boasted to be a progressive female capital with high rates of women's literacy and the practice of "Marumakkathayam" being prevalent (which essentially traces family property to the ownership of the daughter instead of the sons), the more left wing social practices however have still failed to address the trend of gender violence across the nation. Thus, even the prime example of an arguably progressive women's state in India has failed to reduce the statistics of violence against women, pointing to a very dark and ingrained societal problem widespread across India that is only to be further triggered by the Pandemic.

In a report by the National Commission for Women in India there has been a rise from 396 complaints from women (mostly tied to some form of violence) from the period of February 27 to March 22 to 587 reports in the period of March 23 to April 16 [90]. However the numbers are not a true reflection of the number of cases of domestic violence as there is significant under-reporting due to the limited resources and accessibility for women to reach help lines. Research has shown that "domestic violence cases rise significantly as mobility restrictions foster more tensions and strain in the household over security, health and job losses"[79].

Ultimately, women and girls "in particular are facing a greater risk from this pandemic, as they are systematically disadvantaged and often suppressed by poverty, inequality, and marginalization"[79]. The inevitable after shocks of the lockdowns impacting socioeconomic factors has brought new stressors to the population as the struggle to survive not just the virus, but the compounding side effects of the virus has created many multi-dimensional issues in domestic, economic and social life for women.

References

- ↑ Shanze1. (2020). India COVID-19 cases density map [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ↑ Saxena, Sparshita (August 8, 2020). "South India accounts for over 40% of India's active cases, Delhi's count continues to improve: Covid-19 state tally". Hindustan Times.

- ↑ "COVID-19 Statistics for India". Hindustan Times. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Folmar, Steven; Cameron, Mary; Pariyar, Mitra (October 14, 2015). "Digging for Dalit: Social Justice and an Inclusive Anthropology of Nepal". Society for Cultural Anthropology.

- ↑ "IDSN report: Disasters hit Dalits harder". International Dalit Solidarity Network. 2013.

- ↑ Mahendra Dev, S.; Sengupta, Rajeswari (April 2020). "Covid-19: Impact on the Indian Economy". Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- ↑ "About 400 Million Workers in India May Sink into Poverty: UN Report". Economic Times. April 2020.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Choudhury, Chitrangada; Aga, Aniket (27 May 2020). "India's Pandemic Response Is A Caste Atrocity". NDTV (New Delhi Television Limited).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Chunduru, Aditya (9 April 2020). "South India Better Equipped to Deal with Lockdown: ISB Study". Deccan Chronicle.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Kumar, Dileep V. (28 July 2020). "COVID-19 Impact: Economic Crisis Looms Large over Kerala, Warns NDMA". The New Indian Express.

- ↑ Shaji, K.A. (15 May 2020). "Lockdown pushes 200 Dalit families in Kerala into extreme poverty". The Kochi Post.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Alluri, Aparna (7 August 2020). "Coronavirus: How India Breached the Two Million Mark". BBC.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Rani, Jeya (30 July 2020). "Tamil Nadu: Blanket of Silence Over Caste-Based Atrocities During COVID-19 Lockdown". The Wire.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Andhra Pradesh: Dalit Youth Detained for Not Wearing Mask Allegedly Dies in Police Custody". Scroll. July 23, 2020.

- ↑ Varma, Ananya (4 April 2020). "COVID-19 Lockdown: Andhra Pradesh Govt Provides Rs 1000 To 1.3cr BPL Families". Republic World.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Sheldon, Victoria. [culanth.org/fieldsights/covid-19-in-kerala-nature-cure-social-media-and-subaltern-health-activism "Covid-19 in Kerala: Nature Cure, Social Media, and Subaltern Health Activism"].https://culanth.org/fieldsights/covid-19-in-kerala-nature-cure-social-media-and-subaltern-health-activism

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Subramaniam Panneerselvam & Gunanithi Perumal & Subin K.P. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Indigenous People of Tamilnadu – A Medical Anthropological Perspective. Working Papers, Research Association for Interdisciplinary Studies.

- ↑ Subramaniam Panneerselvam & Gunanithi Perumal & Subin K.P. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Indigenous People of Tamilnadu – A Medical Anthropological Perspective. Working Papers, Research Association for Interdisciplinary Studies.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 PTI. “Covid-19 Lockdown Takes Sheen off Tamil Nadu's Tourism Sector, Renders 'Lakhs' Jobless.” The Economic Times, Economic Times, 21 July 2020, economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/covid-19-lockdown-takes-sheen-off-tamil-nadus-tourism-sector-renders-lakhs-jobless/articleshow/77081480.cm

- ↑ Simpson, Edward (2014). The Political Biography of an Earthquake: Aftermath and Amnesia in Gujarat, India. New York, New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Gamburd, Michele R. (2013). Introduction: Political Ethnography of Disaster. Indiana University Press.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Stirrat, Jock. Competitive Humanitarianism: Relief and the Tsunami in Sri Lanka. JSTOR www.jstor.org/stable/4124479: Anthropology Today. pp. pp. 11–16.CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: extra text (link)

- ↑ "Impact of Covid-19 on Indian horticulture & food security". Fresh Plaza.

- ↑ "Impact of Covid-19 on Indian horticulture & food security". Fresh Plaza.

- ↑ "Impact of Covid-19 on Indian horticulture & food security". Fresh Plaza.

- ↑ "Who Is Chandni bibi?: Survival as Embodiment in Disaster Disrupted Northern Pakistan". Direct-selling helps Indian farmers swerve food waste under lockdown.

- ↑ "Who Is Chandni bibi?: Survival as Embodiment in Disaster Disrupted Northern Pakistan". WSQ: Women's Studies Quarterly, 44(1-2).

- ↑ "Who Is Chandni bibi?: Survival as Embodiment in Disaster Disrupted Northern Pakistan". WSQ: Women's Studies Quarterly, 44(1-2).

- ↑ "Direct-selling helps Indian farmers swerve food waste under lockdown".

- ↑ "Dots on the Map: Anthropological Locations and Responses to Nepal's Earthquakes". Society for Cultural Anthropology.

- ↑ "Dots on the Map: Anthropological Locations and Responses to Nepal's Earthquakes". Society For Cultural Anthropology.

- ↑ "Dots on the Map: Anthropological Locations and Responses to Nepal's Earthquakes". Society For Cultural Anthropology.

- ↑ "COVID-19: Dalit rights bodies regret, no relief plan yet for SCs, STs, marginalized".

- ↑ "Our Farmers made up to 80% losses in the lockdown, says Horticulture start-up INI Farms".

- ↑ "Our Farmers made up to 80% losses in the lockdown, says Horticulture start-up INI Farms".

- ↑ "Our Farmers made up to 80% losses in the lockdown, says Horticulture start-up INI Farms".

- ↑ "Introduction". The Political Biography of an Earthquake: Aftermath and Amnesia in Gujarat, India.

- ↑ "The 'shock doctrine' in India's response to COVID-19".

- ↑ "MEPMA to sell banana, ensure MSP to growers".

- ↑ "MEPMA to sell banana, ensure MSP to growers".

- ↑ "COVID-19 and Agriculture: Strategies to mitigate farmers' distress".

- ↑ "COVID-19 and Agriculture: Strategies to mitigate farmers' distress".

- ↑ "COVID-19 and Agriculture: Strategies to mitigate farmers' distress".

- ↑ Altstedter, Pandya, Ari, Dhwani (July 29, 2020). "Herd Immunity May Be Developing in Mumbai's Poorest Areas". Bloomberg. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ↑ Liechty, Mark (2010). "Out Here in Kathmandu": Youth and the Contradictions of Modernity in Urban Nepal. Bloomington, Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 40–42. ISBN 970-0-253-35473-0 Check

|isbn=value: invalid prefix (help). - ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 46.4 Chatterji, Tathagata (May 12, 2020). "Post-pandemic livelihood sustainability and central urban missions". Observer Research Foundation. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ↑ "AMIL NADU ACT 011 OF 1971 : TAMIL NADU SLUM AREAS (IMPROVEMENT AND CLEARANCE) ACT, 1971". casemine.com. May 4, 1971.

- ↑ Bureau, ET (March 9, 2020). "Tamil Nadu reports first case of Coronavirus; patient quarantined in Chennai Government Hospital". The Economic Times. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 Ravishankar, Sandhya (June 16, 2020). "Why Chennai's COVID-19 Cases Are Sky High". The lede. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ↑ "Gurgaon, the new urban India - VPRO documentary - 2009". YouTube.com. October 5, 2009. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ↑ R, Aditi (June 10, 2020). "Chennai: Water scarcity in slums stokes fear of contracting Covid-19". The Times of India. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ↑ Team Sahyog (May 28, 2020). "List of NGOs providing relief during Covid-19". Invest India. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ↑ ANI (July 8, 2020). "Tamil Nadu: Transgender Community NGO Conducts Awareness Campaign Against COVID-19 At Slum Areas". BW Businessworld. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ↑ Vedant Raj, Lohia (August 1, 2020). "Feeding Chennai". Milaap.org. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Stirrat, Jock (October 2006). "Competitive Humanitarianism: Relief and the Tsunami in Sri Lanka". Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 How this border transformed a subcontinent/ India and Pakistan. Youtube. (2020). Retrieved 21 August 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/watchv=r5Ps1TZXAN8&list=PLJ8cMiYb3G5dRe4rC7m8jDaqodjZeLzCZ.

- ↑ Urvashi ,Butalia (2010). Voices from the partition. Dianae P. Mines. Sarah E.Lamb. Everyday life in South Asia, second edition. (314-327.) Indiana university press.

- ↑ Urvashi ,Butalia (2010). Voices from the partition. Dianae P. Mines. Sarah E.Lamb. Everyday life in South Asia, second edition. (316) Indiana university press.

- ↑ Urvashi ,Butalia (2010). Voices from the partition. Dianae P. Mines. Sarah E.Lamb. Everyday life in South Asia, second edition. (314-327) Indiana university press.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 Regan, H., Sur, P., & Sud, V. (2020). Covid-19 amplifies prejudices against India's Muslims. CNN. Retrieved 21 August 2020, from https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/23/asia/india-coronavirus-muslim-targeted-intl-hnk/index.html.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 61.3 61.4 Arun Dev, A., 2020. ‘Don’T Touch Them’: Muslims Attacked In Karnataka Over COVID-19. [online] TheQuint. Available at: <https://www.thequint.com/videos/news-videos/attacks-blaming-muslims-for-covid-19-reported-across-karnataka> [Accessed 21 August 2020].

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Kuthar, G. (2020). Tamil Nadu Lockdown Diary: 'People talk as if COVID-19 came from Melapalayam, not China'; Muslims struggle with health systems steeped in prejudice - India News , Firstpost. Firstpost. Retrieved 22 August 2020, from https://www.firstpost.com/india/people-talk-as-if-covid-19-came-from-melapalayam-not-china-muslims-in-tamil-nadu-struggle-with-health-systems-steeped-in-prejudice-8564271.html.

- ↑ Mayara,Shail(2017).Beyond Ethnicity: Being Hindu and Muslim in South India. Lived Islam in South Asia. Lmtiaz, Ahlmad. Helmut reifeld ed.,(19). Routledge London.

- ↑ Mayara,Shail(2017).Beyond Ethnicity: Being Hindu and Muslim in South India. Lived Islam in South Asia. Lmtiaz, Ahlmad. Helmut reifeld ed.,(32). Routledge London.

- ↑ Jeganathan, P. (2020). [Municipal solid waster collector at work during Covid-19 lockdown] [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ↑ Nowrojee, Binaifer (May 9, 2020). "How a South Indian State Flattened Its Coronavirus Curve". The Diplomat.

- ↑ Pullat, Urmila (July 1, 2020). "The anatomy of a torture complaint". Himal Southasian.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 68.2 Stalin, K. (Director). (2007). India untouched: Stories of a people apart [Film]. Video Volunteers.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Subramanian, Lakshmi (June 28, 2020). "Thoothukudi: How the police, doctors and lower judiciary failed the father-son duo". The Week.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Ravishankar, Sandhya (June 28, 2020). "Three Cops In Sathankulam Leave A Trail Of Violence & Casteism In One Year". The Lede.

- ↑ "Andhra Pradesh: Two policemen suspended for allegedly beating up, tonsuring Dalit youth". Scroll. July 21, 2020.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Ambedkar, B. R. (1944). The Annihilation of Caste (3rd ed.). Columbia University Press. pp. 17–19.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Rajasekaran, Ilangovan (April 2, 2020). "Honour killing in the time of lockdown in Tamil Nadu". Frontline.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Muralidharan, Kavitha (May 3, 2020). "Across Tamil Nadu, Caste Violence Has Increased During the Lockdown, Say Activists". The Wire.

- ↑ Nigam, D. D., & Dubey, S. (2020). Condition of sanitation workers in India: A survey during COVID-19 and lockdown. Independent study report.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Paliath, Shreehari (July 31, 2020). "In India, 90% sanitation workers don't have health insurance even amid the coronavirus crisis". Scroll.

- ↑ Mines, D. P., & Lamb, S. E. (2010). Everyday Life in South Asia, Second Edition. No Publisher.

- ↑ What Explains Gender Disparities in India? What Can Be Done? (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/opinion/2012/09/27/gender-disparities-india

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 79.2 79.3 Diplomat, L. K. (2020, June 24). How COVID-19 Worsens Gender Inequality in Nepal. Retrieved from https://thediplomat.com/2020/06/how-covid-19-worsens-gender-inequality-in-nepal/

- ↑ Delhi, M. K. (2020, May 24). Women in India suffer as Covid-19 lockdown hits sanitary pads supply. Retrieved from https://www.rfi.fr/en/international/20200524-asia-india-coronavirus-women-health-sanitary-napkins-supply-chain-lockdown-migrants-charity

- ↑ DH News Service. (2010, February 01). Poverty decreasing in South India, says UN report. Retrieved from https://www.deccanherald.com/content/50077/poverty-decreasing-south-india-says.html

- ↑ Purohit, K. (2020, April 03). India COVID-19 lockdown means no food or work for rural poor. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/04/india-covid-19-lockdown-means-food-work-rural-poor-200402052048439.html

- ↑ Chakraborty, S. (n.d.). India Suffers Because Women Eat The Last And The Least: Outlook Poshan. Retrieved from https://poshan.outlookindia.com/story/poshan-news-the-game-changer/333941

- ↑ Anand, S., & Fan, V. (2016). The health workforce in India. Human Resources for Health Observer Seires No.16, 1-104. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 Khullar, A. (2020, April 09). Gender analysis missing from India's coronavirus strategy. Retrieved from https://www.deccanherald.com/opinion/gender-analysis-missing-from-india-s-coronavirus-strategy-823349.html

- ↑ Introduction: Children in a digital world. (2018). State of the Worlds Children The State of the World’s Children 2017, 6-11. doi:10.18356/a072d2f4-en

- ↑ Choudhury, C. (2020, May 27). Opinion: India's Pandemic Response Is A Caste Atrocity. Retrieved from https://www.ndtv.com/opinion/india-s-pandemic-response-is-a-caste-atrocity-2236094

- ↑ Kumar, P., & Raja, V. (2018). Gender Inequality in South India. Indian Journal of Waste Management, 2(2). Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ↑ Arun, S. (2017, February 28). How Kerela's gender issues are changing for the worse. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/politics/kerala-was-a-beacon-of-hope-for-india-on-gender-issues-but-things-are-changing-for-the-worse-a7594896.html

- ↑ Pti. (2020, April 17). India witnesses steep rise in crime against women amid lockdown, 587 complaints received: NCW. Retrieved from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/india-witnesses-steep-rise-in-crime-against-women-amid-lockdown-587-complaints-received-ncw/articleshow/75201412.cms