Riot Grrrl

Overview

Riot Grrrl is regarded as a grassroots punk rock third-wave feminism movement, which was established during the 1990s in Washington, D.C. Many scholars state that the formation of Riot Grrrl paved the way for third-wave feminism [1]. Third-wave feminism aims to aid and propel individual identity. It is less focused on laws and politics. Riot Grrrl is regarded as third-wave feminism movement because they aim to empower women and redefine feminine beauty [2]. Some of the issues that Riot Grrrl tackles are body image, racism, rape, domestic violence, and female empowerment.

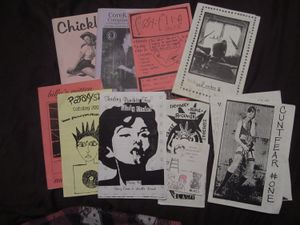

Riot Grrrl has been characterized as a music genre, but it also involves DIY ethic, zines, art, and activism. Through the publication of vines, the movement was able to produce a DIY ethic that rejected consumerism of the mass media. The zine that was established was called Riot Grrrl Press. This contributed to Riot Grrrl’s main objective, which was its objection to mainstream media and encourage female empowerment.

History

Riot Grrrl is a punk rock feminism group that originated in Washington, D.C. during the spring of 1991 [4] . Initially, Riot Grrrl was created to make girls and women more involved in D.C.’s predominantly white, male punk scene. The formation of the Riot Grrrl movement began when the bands Bratmobile and Bikini Kill unified [5]. Allison Wolfe and Molly Neuman (both members of the band Bratmobile) with the help of zine editor Jen Smith created Riot Grrrl [6]. In the beginning stages, Kathleen Hanna, from the band Bikini Kill, would host weekly meetings with around twenty other girls. These weekly meetings were only inclusive to women. They would also use their music to express and open discussions about issues of gendered oppression and violence. These meetings included musicians, artists, activists, zine makers, and members of the punk community. The women involved in these meeting were in their teens to early twenties.

From July 31 to August 2, 1992 Riot Grrrl organized a national convention [7]. Girls from all over the country were brought together to discuss common issues that the movement fought against. Some of these issues included racism, sexism, domestic violence, and patriarchy. At this convention, workshops were offered on an array of things ranging from self-defense to how to create a zine. The convention inspired many participants to create their own Riot Grrrl chapters in their hometowns. By 1993, weekly Riot Grrrl meetings were being held in many cities across the United States. During this time, the movement had also inspired and spread to those living in Europe [8].

In 1993, Erika Rienstien and May Summer established the zine publication Riot Grrrl Press in Washington, D.C. They were able to gain assistance from fellow riot grrrls, Mary Fondriet and Joanna Burgress [9]. The four of them relocated to Arlington, VA to work on Riot Grrrl Press. Riot Grrrl Press was created because many in the movement felt that mainstream media was portraying negative representations that reinforced gender stereotypes. Therefore, Riot Grrrl Press’ main objective was to empower females. The creation of Riot Grrrl Press was something familiar within the punk DIY ethic. DIY ethic in the punk scene embraced the rejection of consumerism of the mass media [10].

By the late 1990’s, the movement’s presence had decline immensely. Many members state that the movement had become something that they were fighting against. It had been consumed by mass media and marketed to pertain to a certain culture. Although some have argued that the movement has dissolved, Riot Grrrl influenced organizations continue to thrive.

Activism

Riot Grrrl’s main objective of their feminist agenda was its opposition to mainstream media and for girls and women to freely express themselves [11]. A radio show was created to showcase programs on feminist history, women’s punk rock music, and vegan cooking. The movement also created a television program that discussed the same issues. The television program was called The Riot Grrrl Varity Show, and aired a total of six episodes. Members of Riot Grrrl also created short films, and art projects.

During the summer of 1992, the Washington D.C. chapter of Riot Grrrl organized a national convention. At the convention there were performances by female bands and poets. Also provided were workshops on sexuality, rape, racism, fat oppression, domestic violence, and self-defense.

References

- ↑ Rundle, L. B. (2005). Grrrls, grrrls, grrrls. Winnipeg: Herizons Magazine, Inc.

- ↑ Rundle, L. B. (2005). Grrrls, grrrls, grrrls. Winnipeg: Herizons Magazine, Inc.

- ↑ https://vimeo.com/67757523

- ↑ DUNN, K., & FARNSWORTH, M. S. (2012). "we ARE the revolution": Riot grrrl press, girl empowerment, and DIY self-publishing. Women's Studies, 41(2), 136-157.

- ↑ DUNN, K., & FARNSWORTH, M. S. (2012). "we ARE the revolution": Riot grrrl press, girl empowerment, and DIY self-publishing. Women's Studies, 41(2), 136-157.

- ↑ DUNN, K., & FARNSWORTH, M. S. (2012). "we ARE the revolution": Riot grrrl press, girl empowerment, and DIY self-publishing. Women's Studies, 41(2), 136-157.

- ↑ DUNN, K., & FARNSWORTH, M. S. (2012). "we ARE the revolution": Riot grrrl press, girl empowerment, and DIY self-publishing. Women's Studies, 41(2), 136-157.

- ↑ DUNN, K., & FARNSWORTH, M. S. (2012). "we ARE the revolution": Riot grrrl press, girl empowerment, and DIY self-publishing. Women's Studies, 41(2), 136-157.

- ↑ DUNN, K., & FARNSWORTH, M. S. (2012). "we ARE the revolution": Riot grrrl press, girl empowerment, and DIY self-publishing. Women's Studies, 41(2), 136-157.

- ↑ Rundle, L. B. (2005). Grrrls, grrrls, grrrls. Winnipeg: Herizons Magazine, Inc.

- ↑ Rundle, L. B. (2005). Grrrls, grrrls, grrrls. Winnipeg: Herizons Magazine, Inc.