Reproduction in Developing Countries

Overview

Family planning, broadly, is anticipating -with the ability to control and attain- a couple or individual’s desired number of children, along with the spacing and timing of births[1]. It’s toted as one of the great public health advances of the past century. Family planning empowers women by lightening excessive childbearing, reduces poverty, granting them the ability attain higher education, obtain better economic opportunities, and results in the avoidance of unsafe abortions and maternal and infant mortality[2][3]. It opens up a field of reproductive choices and grants further autonomy and choice in their lives[4]. It also has the effect of enhancing environmental sustainability and stabilising Earth’s population[5]. Family Planning in developing countries is an issue that correlates and intersects with these various determinants of women's health and well-being both individually and in their communities. In developing countries, an estimated 225 million women would like to delay or stop childbearing, but are not using any method of contraception, due to the lack of access to contraceptives or family planning information or services.[6]

Reproductive Rights

Sexual and Reproductive Rights (SSR) were outlined and defined in the 1995 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) Programme of Action. These rights, to list a few, involve voluntary, informed, and affordable family planning services, assisted childbirth from a trained attendant, prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV and AIDS, safe and accessible post-abortion care, and where legal, access to safe abortion services[7]. Even still, access to reproductive health care and access to modern contraceptive methods is the main barrier when considering the use or lack of family planning in developing regions.

Contraception

According to the World Health Organization, in sub-Saharan Africa, one in four women who wish to delay or stop having children do not use any family planning methods, and less than 20 percent of women in that area use modern contraceptives.[8] Contraception is a critical requirement for the health of women, girls and families, and globally, contraceptive use has risen from 54% in 1990 to 57% in 2014[9][10]. Numbers vary from region to region – generally in Africa contraceptive use is low: 27.6% in 2014[11]. The accessibility and availability of modern contraceptives in developing countries is limited, as well as in choice of method available – these are the most impactful challenges. According to the World Health Organization, in sub-Saharan Africa, one in four women who wish to delay or stop having children do not use any family planning methods, and less than 20 percent of women in that area use modern contraceptives[12].

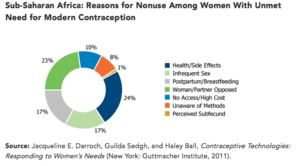

Unmet need (those sexually active but not using any contraceptive method and report not wanting any more children or wanting to delay future children)[13] is especially high in vulnerable groups such as the poor, adolescents, refugees, urban slum dwellers, and women in the postpartum period[14]. In developing countries, many times the repression of women or the lack of autonomy in their lives prevents the agency or control of their reproductive choices. Family planning in many countries initially was restricted to health facilities, following strict eligibility criteria and sexist and shaming constraints, for example: written consent of husband, proof of marital status, age, insistence that only menstruating women be allowed to start contraception[15]. Many family planning education programmes have helped dismantle this approach, but public sector delivery systems are still the main outlet for information and supplies. A few important barriers to contraceptive use are: insufficient knowledge about contraceptive methods and how to use them; fear of social disapproval, religious opposition, or cultural reasons; fear of side-effects and health concerns; women’s perceptions of husbands’ opposition, limited choice of methods and limited access (especially in poorer segments of population or unmarried people), gender-based barriers) [16][17]

Abortion

Family planning reduces the need for abortion, especially when it comes to unsafe abortion. Unsafe abortion is defined as: “a procedure for terminating an unintended pregnancy carried out either by persons lacking the necessary skills or in an environment that does not conform to minimal medical standards, or both.”[18]In developing countries the access to safe and legal abortion is limited. About 25% of the worlds population lives in countries with highly restrictive abortion laws, mostly in developing countries in Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Approximately 68,000 women die of unsafe abortion annually, which makes it one of the leading causes of maternal mortality[19]Pregnant adolescents are more likely than adults to have unsafe abortions, and these unsafe procedures as well as complications from pregnancy and childbirth are also an important cause of death among girls aged 15-19 in low and middle income countries. Unsafe abortions can contribute to lasting health problems and maternal deaths - approximately 97% of unsafe abortions are performed in developing countries where further access to medical care may be limited[20]

Abortion laws do not prevent women from seeking abortions – instead it ensures that women will seek out dangerous abortions, risking their health and putting their lives in jeopardy. Women's reproductive rights are respected in varying degrees across developing countries – but the right to make a decision regarding a decision to carry a pregnancy to term or not is one that is one that is still being worked on by activists and international human rights boards. For example, in 2006 in Colombia, women’s sexual and reproductive rights were recognized in court as human rights and constitutional rights, which allowed the court to overturn the abortion ban previously held[21]. Although still held to strict restrictions (pregnancy must threaten the woman’s life or health, in cases of rape or incest, and where the fetus is incompatible with life), it is a step in the right direction of safe and legal abortion in Colombia[22]. There is an association with unsafe abortions and restrictive abortion laws - which connects to the fact that in developing countries, two-thirds of unintended pregnancies occur among women who were not using contraceptive methods [23].

Benefits of family planning or contraceptive use[24][25]

- preventing pregnancy related health risks in women

- reducing infant mortality

- helping to prevent HIV/AIDS

- empowering women and enhancing education

- reducing adolescent pregnancies

- slowing population growth

Conclusions

Family planning is an imperative notion for the success of our future world – the environment, sky-rocketing population, widespread poverty, sexually transmitted infections, and high rates of maternal deaths and unsafe abortions point to a great need for more education, resources, and political action. It is a cyclical issue – being born into poverty affords one little resources, which may mean little education. Educating women is one of the key factors in building stronger communities in developing countries. The intersectionality between poverty, gender roles and expectations, and human rights and laws brings women to an incredible disadvantage in developing countries when considering family planning and leaves them devoid of agency or ability of choice when faced with reproductive decisions.

Interesting Links and further resources

References

- ↑ http://www.who.int/topics/family_planning/en/

- ↑ Ross, John, Hardee, Karen, Mumford, Elizabeth, Eid, Sherrine. "Contraceptive Method Choice in Developing Countries". International Family Planning Perspectives, March 2002.

- ↑ http://who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs351/en/

- ↑ Ross, John, Hardee, Karen, Mumford, Elizabeth, Eid, Sherrine. "Contraceptive Method Choice in Developing Countries". International Family Planning Perspectives, March 2002.

- ↑ he Lancet : John Cleland, Stan Bernstein, Alex Ezeh, Anibal Faundes, Anna Glasier, Jolene Innis. Family planning: the unfinished agenda. The Lancet Sexual and Reproductive Health Series, October 2006.

- ↑ http://who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs351/en/

- ↑ http://www.amnestyusa.org/pdfs/SexualReproductiveRightsFactSheet.pdf

- ↑ http://who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs334/en/

- ↑ http://who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs351/en/

- ↑ K.A. Harrison, C.T. John, Silvia Ojoo, TubonyeC. Harry, Maternal health in developing countries, The Lancet, Volume 347, Issue 8998, 1996, Page 400, ISSN 0140-6736, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(96)90578-4. (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673696905784)

- ↑ http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs351/en/

- ↑ http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs351/en/

- ↑ http://www.prb.org/Publications/Media-Guides/2012/unmet-need-factsheet.aspx

- ↑ http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/family_planning/unmet_need_fp/en/

- ↑ http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/general/lancet_3.pdf

- ↑ http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/general/lancet_3.pdf

- ↑ http://www.prb.org/Publications/Media-Guides/2012/unmet-need-factsheet.aspx

- ↑ Haddad LB, Nour NM. Unsafe Abortion: Unnecessary Maternal Mortality. Reviews in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2009;2(2):122-126.

- ↑ Haddad LB, Nour NM. Unsafe Abortion: Unnecessary Maternal Mortality. Reviews in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2009;2(2):122-126.

- ↑ >Haddad LB, Nour NM. Unsafe Abortion: Unnecessary Maternal Mortality. Reviews in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2009;2(2):122-126.

- ↑ https://www.womenonweb.org/en/page/619/abortion-laws-worldwide

- ↑ https://www.womenonweb.org/en/page/619/abortion-laws-worldwide

- ↑ Haddad LB, Nour NM. Unsafe Abortion: Unnecessary Maternal Mortality. Reviews in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2009;2(2):122-126.

- ↑ Haddad LB, Nour NM. Unsafe Abortion: Unnecessary Maternal Mortality. Reviews in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2009;2(2):122-126.

- ↑ http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs351/en/