Orientalism: Constructing the Orient/Occident Binary

Orientalism is a postcolonial discourse that considers the Eurocentric construction of an artificial binary opposition between the Western world (the Occident) and the Eastern world (the Orient), primarily the Middle East and Asia. This East-West dichotomy identifies, designates, and subordinates the peoples of the Orient as the Other establishing the West as the superior in an unequal power relation to justify imperialism and colonialism.[1] Orientalism has taken a variety of forms, such as the exoticism, essentialism and racialization of Eastern people and cultural practices, eroticizing Oriental women while emasculating the men, gendering of civilizations, objectifying, and institutionalizing racism.[2] Its discrimination and prejudice is found in academia, art, and pop culture, and continues to influence contemporary political and cultural perspectives.[3] Today, referring to people today as orientals is regarded as insensitive and politically incorrect due to the negative associations as an ahistorical essence and a polemical accusation.[4]

Edward Said and Orientalism

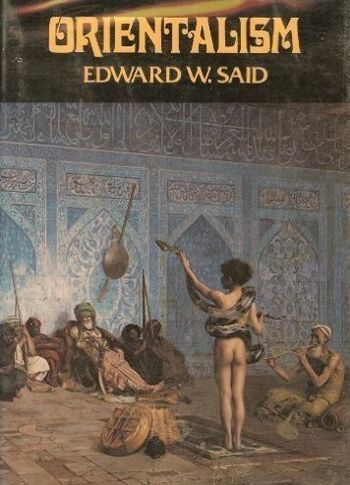

Although Orientalist attitudes can be traced from the eleventh-century Crusades, transcontinental trade, and increased travel, which established the concept of Europe as a conglomerate, distinctive, and a beacon of superior civilization, Edward W. Said (November 1935 – 25 September 2003) first introduced the term in his influential and controversial book Orientalism (1979).[5][6] A Palestinian-American professor and cultural theorist, Said utilized his education and bi-cultural perspective to illuminate the gaps of cultural and political understanding between the Western and the Eastern worlds.[7]

Through a comparative review of European colonial arts and literature on the Middle East, he wrenched the term out of its disciplinary context and demonstrated how European and American government bureaucrats, academics, cultural workers, and common sense defined and circumscribed false knowledge about the Orient.[8][9]

In the late 1700s, the West viewed the East as 'past in the present' showing a bygone state of society compared with the new realities of modernizing Europe and declared Europe the future of the East. This cultural generalization justified colonization as being either a liberation or an improvement in the lot of the peoples subjected to Oriental despotism. [10] Said theorized that the Orient had been constructed and appropriated as a projection of Western desire in an effort to not only rationalize imperialism and colonialism but also to mask the power abuses of it,

"The corporate institution for dealing with the Orient—dealing with it by making statements about it, authorizing views of it, describing it, by teaching it, settling it, ruling over it: in short, Orientalism as a Western style for dominating, restructuring, and having authority over the Orient."[11]

The Orientalist ideological bias and identity binary is ultimately created through the construction of the Other.

Constructing the Other

In 1849, the American Henry David Thoreau wrote,

“Behold the difference between the Oriental and the Occidental. The former has nothing to do in this world; the latter is full of activity. The one looks in the sun till his eyes are put out; the other follows him prone in his westward course”.[12]

The Orientalist dichotomy assumes the absolute primacy of a Eurocentric perspective. Through the Western's construction of the image, idea, personality, and experience of the East, it categorically objectifies what is not European, rendering the Orient exotic and essentially Other (the non–European Self).[13][14]

This sharp divide of 'the West versus the Rest' is formed through homogenization (portraying the myriad of Eastern cultures and people as one single monolithic Orient), essentialization (reducing them to the artificial essence of universal innate characteristics), and feminization (aligning them on the inferior end of the patriarchal male/female binary relationship). [15][16]

The colonial West constructed its identity largely by saying what others were not.[17] Everywhere it declared itself the masculine superior standard of culture, it shaped the homogenous image of the feminine Other as inferior.[18] Associations of the Orient with women in patriarchal colonial times contained strong connotations of desire, penetration, and conquest. Other arbitrary and culturally constructed West/East binary examples include centre/periphery, powerful/weak, active/passive, civilized/savage, rational/emotional, modern/timeless, sensible/erotic, clean/dirty, pure/corrupt, advancing/decaying, and democratic/totalistic.[19]

Visual Orientalism

Although figures in Middle Eastern dress appear in Renaissance and Baroque works by such artists as Giovanni Bellini and Rembrandt van Rijn, nineteenth-century colonialism produced an astonishing array of scholarly, artistic, and popular culture renderings of the Orient that represented it in ways that accorded with social and racial ideologies popular at the time.[20][21]

Orientalism in the fine arts is exceptionally prominent in early-1800s French paintings made during France's Algerian occupation.[22] Some nineteenth-century Orientalist paintings were intended as French imperialist propaganda by depicting an essentialist East as a sensuous place of backwardness, lawlessness, or barbarism, enlightened and tamed by French rule.[23] Many French painters, such as Jean-Auguste-Dominique Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Antoine-Jean Gros, were influenced by the aesthetic's opulent eroticism although they had never visited the East in person.[24] Works of these Western visual projections that focus on the mysterious and sexually available femme fatale, and decadent and incorrect, harem fantasies include Ingres' Grand Odalisque, and Eugène Delacroix's Women of Algiers in their Apartment and The Death of Sardanapalus.

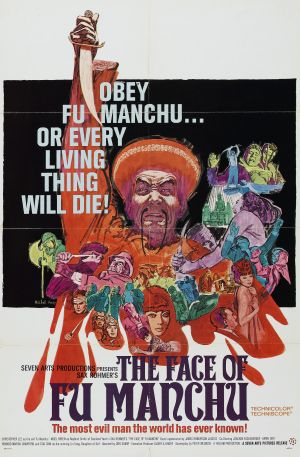

Negative cliché fantasies of the East are also evident in film. Western movies portraying Asian and Middle Eastern men typically represent them as feminine, ugly, cunning, dangerous, and villainous, while the women are depicted as weak, erotic, mysterious, and objects of conquest such as geishas or harem inhabitants.[25] Through the Western lens, these unfavourable ethnic stereotypes are active in characters like Fu Manchu, Aladdin, and Mulan.

Said comments on contemporary Orientalism:

"One aspect of the electronic, postmodern world is that there has been a reinforcement of the stereotypes by which the Orient is viewed. Television, the films, and all the media's resources have forced information into more and more standardized molds. So far as the Orient is concerned, standardization and cultural stereotyping have intensified the hold of the nineteenth-century academic and imaginative demonology of the 'mysterious Orient.' This is nowhere more true than the ways by which the Near East is grasped."[26]

Limitations

A number of scholars have debated the premises and limitations of Orientalism and Said's work.[27] The concept of has been critiqued as an overly general application, which may describe the French or English view, though not, for example, the German one.[28] It may be accused of participating in the same binary between Orient and Occident that it critiques: constructing the West as not only monolithic, but also as having the supreme power to misrepresent and dominate “the Rest.” [29] Additionally, it underestimates the strong tradition within Oriental writing that draws ontological distinctions between East and West.[30]

See also

UBC Wiki: Orientalism

Black Orientalism

Frantz_Fanon

Islamophobia

Neo-orientalism

Oriental Studies

Orientalist Art

Social Darwinism

Structuralism

Further Reading

UBC Library Books

Said, Edward W. Orientalism (First Edition). Vintage Books, 1979.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism (Updated). Penguin, 2003.

Sardar, Ziauddin. Orientalism. Open University Press, 1999.

Sheehi, Stephen. Islamophobia. Clarity Press, 2011.

Young, Robert. Postcolonialism. Blackwell Publishers, 2001.

References

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Other

- ↑ http://site.ebrary.com/lib/ubc/reader.action?docID=10927928&ppg=920

- ↑ http://site.ebrary.com/lib/ubc/reader.action?docID=10927928&ppg=920

- ↑ http://sk.sagepub.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/reference/intlpoliticalscience/n403.xml

- ↑ http://site.ebrary.com/lib/ubc/reader.action?docID=10927928&ppg=920

- ↑ http://go.galegroup.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/ps/i.do?p=GVRL&u=ubcolumbia&id=GALE%7CCX4190600335&v=2.1&it=r&sid=summon&authCount=1

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Said

- ↑ http://site.ebrary.com/lib/ubc/reader.action?docID=10927928&ppg=920

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/stable/pdf/j.ctt1287j69.52.pdf

- ↑ http://sk.sagepub.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/reference/intlpoliticalscience/n403.xml

- ↑ http://site.ebrary.com/lib/ubc/reader.action?docID=10927928&ppg=920

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/stable/pdf/j.ctt1287j69.52.pdf

- ↑ http://sk.sagepub.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/reference/intlpoliticalscience/n403.xml

- ↑ http://site.ebrary.com/lib/ubc/reader.action?docID=10927928&ppg=920

- ↑ http://go.galegroup.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/ps/i.do?p=GVRL&u=ubcolumbia&id=GALE%7CCX4190600335&v=2.1&it=r&sid=summon&authCount=1

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Other

- ↑ http://site.ebrary.com/lib/ubc/reader.action?docID=10927928&ppg=920

- ↑ http://site.ebrary.com/lib/ubc/reader.action?docID=10927928&ppg=920

- ↑ http://site.ebrary.com/lib/ubc/reader.action?docID=10927928&ppg=920

- ↑ http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/euor/hd_euor.htm

- ↑ http://go.galegroup.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/ps/i.do?p=GVRL&u=ubcolumbia&id=GALE%7CCX4190600335&v=2.1&it=r&sid=summon&authCount=1

- ↑ http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/758416162?pq-origsite=summon&accountid=14656

- ↑ http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/euor/hd_euor.htm

- ↑ http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/758416162?pq-origsite=summon&accountid=14656

- ↑ http://site.ebrary.com/lib/ubc/reader.action?docID=10927928&ppg=920

- ↑ http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/758416162?pq-origsite=summon&accountid=14656

- ↑ http://go.galegroup.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/ps/i.do?p=GVRL&u=ubcolumbia&id=GALE%7CCX4190600335&v=2.1&it=r&sid=summon&authCount=1

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/stable/pdf/j.ctt1287j69.52.pdf

- ↑ http://go.galegroup.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/ps/i.do?p=GVRL&u=ubcolumbia&id=GALE%7CCX4190600335&v=2.1&it=r&sid=summon&authCount=1

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/stable/pdf/j.ctt1287j69.52.pdf