Old El Paso: Hard & Soft Taco Kits

Introduction

In the nineteenth century, the taco was primarily consumed by Mexican peasants but today it is an industrialized, appropriated, globally marketed commodity. By tracing its history, this wiki shows that the taco is a product of contacts between many cultures, although it is often imagined as a chiefly Mexican product. Cultural hegemony and false fantasies of Spanish heritage[1] has prevented pre-Hispanic natives and their Mexican successors from receiving acknowledgement for their contributions to the taco and its family. This wiki goes back as far as pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica[2], to highlight the contributions of indigenous people towards the making of the taco, against challenges posed by Mexican nationalists who tried to claim the taco as their own, and restaurateurs who looked to appropriate this food for Anglo clientele. Also, there is a section on historical phenomena like colonization and post-war industrialization, as well as a look at Tex-Mex cuisine. All examination and analysis is carried out through the case study of a recipe kit from a brand called Old El Paso.

At First Glance

Old El Paso: Hard & Soft Taco Kit is a recipe kit from Old El Paso, a brand by General Mills, that is dedicated to Mexican-style foods. Since the early twentieth century, these kits have typically been found in the ‘Mexican’ or ‘International’ aisle of most North American supermarkets and convenience stores for CAD$2 to $4.[3] The kit is made up of an inexpensive cardboard packaging and includes dry ingredients, sauces, seasonings, tortilla shells and flour tortillas. The kit recipe requires consumers to use ingredients like ground beef, as filling, along with their choice of other ingredients such as lettuce, cheese and salsa. The mild form of taco sauce is highlighted on the cover to entice Anglo palates that are averse to strong spices. The word ‘Old' in 'Ol El Paso’ might have catered to progressive Anglo-Americans of the early twentieth century who fantasized about Spanish heritage that was disappearing in the face of growing gentrification[4] and metropolitanization[5] after the seizure of the city of El Paso by Texas, as a part of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848[1][6].

Origins of the Taco

The Corn Tortilla

The corn tortilla has its origins in the Mesoamerican kitchen of early centuries of the Common Era, otherwise known as the Christian Era, when Indians nixtamalized[7], maize to enrich their nutritional value. Nixtamalization produced corn kernels which were ground on a metate[8] through the enormous labor of peasant Indian women.[9] These women often used the tortilla as a wrapper to send food to male relatives engaged in manual labor like mining, well before this food came to be referred as the ‘taco’ in dictionaries in the nineteenth century. Historian Jeffrey M. Pilcher argues that the word ‘taco’ derives from its usage by silver miners to refer to pluggable explosives.[10] The corn tortilla remained popular among the poor indigenous people because of its prolific yields in marginal lands, despite pressure from the Spanish missionaries to substitute corn with wheat.[9] The cultivation of wheat shifted to northern frontiers of Mesoamerica, where climate was more compatible.

Emergence of Flour Tortillas

It is unclear whether the flour tortilla was an invention of the indigenous women, who worked under Spanish conquistadors, otherwise known as leaders or conquerors, or whether it was carried over by Mediterranean migrants. In northern Mexico, wheat increasingly became the preferred ingredient for making tortillas over corn because of its climatic suitability and easier preparation methods. Furthermore, wheat’s political associations with Spanish conquistadors also facilitated the transition from corn to flour tortillas, which have become quite popular today.[11] This significant emergence of flour tortillas is displayed in the Old El Paso kit, which comes with six flour tortillas.[3]

Introduction of Livestock

Besides wheat, meat became readily available after the Spanish introduced livestock, much to the dismay of natives. Although the grazing of cattle displaced many natives, they eventually overcame their conflict with meat and began raising animals; chicken in particular came to constitute a significant part of their diet.[12] The addition of meat is reflected in the recipe provided with the Old El Paso kit, where ground beef is required to be added as filling for the taco.

The Spices of Global Trade

Old El Paso’s taco seasoning usually consists of chili pepper, red pepper, garlic and salt. While chilies are native to South America and were cultivated by Mexicans prior to the discovery of the New World, otherwise known as the Americas, most of the components of seasoning were introduced after the discovery of the New World, a good example being garlic native to Central Asia.

The Migrant Worker’s Taco

During the turn of the nineteenth century, the taco gained attention from culture observers and culinary intellectuals, who published expensive taco recipes using French crepes and pastry cream in an attempt to cleanse the taco of its plebeian image. This practice has no doubt impacted the modern day taco; in fact, one variation of the Old El Paso’s kit cover shows tacos containing sour cream in them (refer to the cover image on top). The proletarian, or commoner, taco was simultaneously evolving independently of these upscale cookbook variations, as migrant workers traveled their country and borrowed cooking ideas from their Lebanese neighbors to create a variation of the traditional taco, the tacos al pastor. Internal movement, largely due to the influx of many immigrants, mainly Mexican, into the country in the 1900s, resulted in the creation of regional flavors of tacos that migrants carried across the border in light of new economic opportunities created by the growing American economy (refer to image of paperboys eating tacos).[13]

The Mexican-American Taco

In the United States, the taco changed again. Elements of the modern Old El Paso taco such as the flour tortilla, ground beef, iceberg lettuce and cheddar cheese emerged as Mexican-Americans adapted locally available foods as a result of the growth in industrial slaughter, refrigerated transport, the dairy industry and in yields of produce. Also, flour replaced corn for tortillas since corn mills were relatively sparser than flour mills in the United States. With these ingredients, the taco began its Anglo-appropriation.[14]

The Industrial Taco

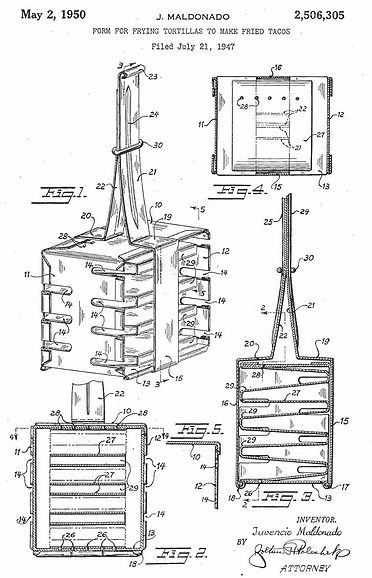

The post-war years saw Mexican-Americans gaining disposable incomes, which they directed towards industrializing and marketing their foods. For example, New York restaurateur Juvencio Maldonado, among several others, filed a patent for frying tortillas into the characteristic U-shaped taco shell to which fillings could be added.[15] The taco shell made it easier for non-Mexicans to eat tacos, while also improving efficiency of producing tortillas across fast food chains (refer to image of patent below). Furthermore, taco shells could be packaged and sold across supermarkets and consumed when desired, which further enabled the taco to infiltrate American households

Historical Forces Behind The Taco

Unequal Cultural Exchange

For indigenous pre-Hispanic Mesoamericans, cultural exchange with the Spanish was unequal. Colonists often enforced their own diet preferences upon their subjects, in order to recreate their European society. An example of such an unequal colonial exchange is the flour tortilla and the corresponding denouncement of corn and maize. The flour tortilla emerged after the Spanish forced natives to cultivate wheat in an attempt to ‘civilize’ them. However, in reality, the idea was to institutionalize colonial control over native land and labour. Wheat gained acceptance in the northern frontiers of Mesoamerica, in light of a favourable climate and growing internalized racism among indigenous subjects who began to denounce their native corn. Another reason why the Spanish looked to wheat was because they feared that a corn diet would cause their bodies to degenerate and resemble their subjects’. Enforced assimilation substituted cross-cultural understanding as the Spanish failed to recognize the contribution of natives to their own diet. For example, native women often laboured to produce flour tortillas for their masters.

Another example of unequal cultural exchange and an instrument of conquest was livestock. Unrestricted grazing by cattle and sheep caused devastation to indigenous crops and the fertility of soil. Loss of livelihood raised conflicts between the colonists and natives, who found themselves pushed onto marginal lands. Cuisines became more carnivorous, as grazing undermined cultivation of natal vegetables, herbs and spices.[16] Simultaneously, majority of the meat harvests went towards feeding the Spanish, as natives were left with only a fraction of meat.

A Gentrified Taco

The legacy of indigenous oppression continued with culinary gentrification[4] by elitist Creoles in nineteenth century Mexico, which brought forth a plethora of taco recipes. In these recipes, culinary intellectuals and upscale restaurateurs used expensive ingredients to separate themselves from impoverished migrant workers and peasants, who were viewed as extensions of the barbaric Aztec natives. For example, one version of the taco, tacos de crema, from the magazine El Diario del Hodar (The Daily of the Home), required the use of French-style crepes over the traditional tortilla and involved stuffing them with pastry cream. These magazines and cookbooks engaged in culinary tourism that was aimed to conceal the indigenous role in the creation of the taco and other dishes. Racial and economic hierarchies were also primary reasons behind such oppressive behaviours, as upscale members of society, namely elitist Creoles, claimed ownership of things such as the taco.

Appropriation[17]

In the United States, many Anglo-Americans carried negative preconceptions about Mexican immigrants, though there were some progressives in Southern California and San Antonio who felt nostalgic about a Mexican era long gone. It was only in the latter half of twentieth century that Mexicans were able to break away from these unfair representations after long protests to end discriminatory employment. They used their new wealth to engage in culinary tourism. In light of growing sales of restaurant food and the emergence of McDonald’s-style fast food service during the post-war years, Mexican cooks adapted their tacos with the use of a milder taco sauce and fried tortilla shells to attract mainstream Anglo clientele, who were unfamiliar with Mexican food.[18] Once again, the Old World, comprised of Asia, Africa and Europe, native cuisine lost out to appropriation, as their cuisine came to be recognized in the food-processing sector. Companies like Old El Paso launched recipe easy-to-prepare kits, which enabled Anglo-Americans to experiment with exotic ‘Mexican’ cuisine, without having to venture into ethnic enclaves. Cultural appropriation meant that progressive Anglos could indulge in their nostalgia about the old Mexican era.[19]

In fact, kits are not Mexican or the native Mesoamerican, but rather a conception of what would be appropriate for Mexico to be like, according to Anglo or European sensibilities that do not reconcile with centuries of oppression and disenfranchisement.

The Global Taco

The taco’s native and national roots became even less important as American expatriates and military personnel began selling Mexican cuisine overseas. In light of a growing tourism and exposure to cultures through film and food, demand for Mexican cuisine grew as well. French infatuation with all things Texan caused a struggling Mexican eatery, called Le Studio, to become a sensation. After the war, supply depots on the military front were filled with chili con carne and during the Pacific War troops consumed taco rations. During the Berlin Crisis, soldiers had invented wiener-schnitzel tamales. On the other hand, inspired restaurateurs, like Chef Oshima Bari in Osaka, Japan, vied for authenticity, as they imported ingredients from North America. However, many others just adapted Mexican foods to fit in locally, resulting in the creation of fusion foods as the taco’s legacy of being a product of cultures continued.[20]

The Taco’s Tex-Mex Family

A similar trend of appropriation, industrialization and globalization can be observed with the taco’s broader Tex-Mex family. The late nineteenth century saw the prominence of chili queens who operated chili stands in public plazas across San Antonio.[21]. Despite negative stereotypes regarding poor hygiene and criminalization of chili vendors, Anglo-Americans adopted these new flavours and added it to their hot dogs and spaghetti, while African Americans introduced modified Mexican flavoured dishes in the Mississippi region. Anglo adaptation stripped Mexican foods of their indigenous ethnicity by taming chilies down for their unaccustomed palates.[16] Mexican food continued to be regarded as lower-class food and did not enjoy any national presence until it was taken over by Anglo-American corporations, like Taco Bell and Old El Paso, who appropriated and mass marketed the cuisine and made the bulk of the profit off the cuisine. The result of the Anglo takeover came in the form of popular items through refried beans, canned sauces and dried chili powders, as Mexican cuisine became a fad in the 1970s. Tex-Mex restaurants emerged in cities with large Mexican populations and food became trendy and appealing to younger generations. Also, new items, including chimichangas, burritos and nachos, were invented and introduced as new Tex-Mex foods. By 1990, the yearly supermarket sale of Mexican foods reached $3 billion[16] and by 2012, the industry had accrued an annual revenue of $31 billion[22]. However, the Mexican-American community has barely benefited from this growth, as they continue to live in substandard ethnic enclaves and crude shacks, which reveals the same asymmetric power relations referred to in earlier sections, where Anglo-American or European people have held hegemonic power and influence. Anglo ways of thinking justified the inferiority of Mexicans, which forged class structures that greatly disadvantaged them and denied them of opportunities, particularly in the education and labor force, to improve their status.

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Jeffrey M. Pilcher, “Who Chased Out the “Chili Queens”? Gender, Race, and Urban Reform in San Antonio, Texas, 1880–1943,” Taylor and Francis Online, 4 (Sep 2008): 194.

- ↑ "Mesoamerican Civilization," Encyclopedia Britannica Online, <http://www.britannica.com/topic/Mesoamerican-civilization> Web. 28 Nov. 2015.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Old El Paso Hard and Soft Dinner Kit | Walmart.ca," Old El Paso Hard and Soft Dinner Kit | Walmart.ca, <http://www.walmart.ca/en/ip/old-el-paso-hard-and-soft-dinner-kit/6000188246704> Web. 27 Nov. 2015.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Gentrification," Merriam-Webster, <http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/gentrification> Web. 17 Nov. 2015.

- ↑ "Metropolitanization," Dictionary.com, Random House, Inc. <http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/metropolitanization> Web. 17 Nov. 2015.

- ↑ Jeffrey M. Pilcher, "Was the Taco Invented in Southern California?," Gastronomica: 31-32.

- ↑ Kimi Harris, "Wisdom From The Past: Nixtamalization of Corn," The Nourishing Gourmet, <http://www.thenourishinggourmet.com/2009/03/wisdom-from-the-past-nixtamalization-of-corn.html> Web. 17 Nov. 2015.

- ↑ "Metate" Dictionary.com. Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House, Inc. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/metate (accessed: November 27, 2015)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Jeffrey M. Pilcher, "Maize and the Making of Mexico," In Planet Taco: A Global History of Mexican Food, 24-27, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- ↑ Jeffrey M. Pilcher, "Was the Taco Invented in Southern California?," Gastronomica: 28.

- ↑ Jeffrey M. Pilcher, "Burritos in the Borderlands," In Planet Taco: A Global History of Mexican Food, 47-75, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- ↑ Jeffrey M. Pilcher, "Maize and the Making of Mexico," In Planet Taco: A Global History of Mexican Food, 28-30, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- ↑ Jeffrey M. Pilcher, "Was the Taco Invented in Southern California?," Gastronomica: 29-30.

- ↑ Jeffrey M. Pilcher, "Was the Taco Invented in Southern California?," Gastronomica: 31.

- ↑ Warren Belasco and Roger Horowitz, In Food Chains: From Farmyard to Shopping Cart, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010, Project MUSE, <https://muse.jhu.edu/>, 163-164, Web. 26 Nov. 2015.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Jeffrey M. Pilcher, “Tex-mex, Cal-mex, New Mex, or Whose Mex? Notes on the Historical Geography of Southwestern Cuisine,” Journal of the Southwest: 659–679, <http://www.jstor.org/stable/40170174> Web. 17 Nov. 2015.

- ↑ "Appropriation," Vocabulary.com, <http://www.vocabulary.com/dictionary/appropriation> Web. 17 Nov. 2015.

- ↑ Jeffrey M. Pilcher, "Inventing the Mexican American Taco," In Planet Taco: A Global History of Mexican Food, 131, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- ↑ Jeffrey M. Pilcher, "Inventing the Mexican American Taco," In Planet Taco: A Global History of Mexican Food, 140-145, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- ↑ Warren Belasco and Roger Horowitz, In Food Chains: From Farmyard to Shopping Cart, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010, Project MUSE, <https://muse.jhu.edu/> 167, Web. 26 Nov. 2015.

- ↑ Jeffrey M. Pilcher, “Who Chased Out the “Chili Queens”? Gender, Race, and Urban Reform in San Antonio, Texas, 1880–1943,” Taylor and Francis Online, 4 (Sep 2008): 173—200.

- ↑ “The History of Taco,” Food Infographics, <https://www.finedininglovers.com/blog/food-drinks/the-history-of-taco-food-infographic/> Web. 17 Nov. 2015.

List of References

"Appropriation." Vocabulary.com. <http://www.vocabulary.com/dictionary/appropriation> Web. 17 Nov. 2015.

Belasco, Warren and Horowitz, Roger. In Food Chains: From Farmyard to Shopping Cart, 163-167. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010. <https://muse.jhu.edu/> Web. 26 Nov.

- 2015.

"Gentrification." Merriam-Webster. <http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/gentrification> Web. 17 Nov. 2015.

Harris, Kimi. "Wisdom From The Past: Nixtamalization of Corn." The Nourishing Gourmet. <http://www.thenourishinggourmet.com/2009/03/wisdom-from-the-past-nixtamalization-of-corn.html>

- Web. 17 Nov. 2015.

"Metate" Dictionary.com. Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House, Inc. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/metate (accessed: November 27, 2015)

"Mesoamerican Civilization." Encyclopedia Britannica Online. <http://www.britannica.com/topic/Mesoamerican-civilization> Web. 28 Nov. 2015.

"Metropolitanization." Dictionary.com. Random House, Inc. <http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/metropolitanization> Web. 17 Nov. 2015.

"Old El Paso Hard and Soft Dinner Kit | Walmart.ca." Old El Paso Hard and Soft Dinner Kit | Walmart.ca. <http://www.walmart.ca/en/ip/old-el-paso-hard-and-soft-dinner-kit/6000188246704>

- Web. 27 Nov. 2015.

Pilcher, Jeffrey M. "Burritos in the Borderlands." In Planet Taco: A Global History of Mexican Food, 47-75. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Pilcher, Jeffrey M. "Inventing the Mexican American Taco." In Planet Taco: A Global History of Mexican Food, 131-145. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Pilcher, Jeffrey M. "Maize and the Making of Mexico." In Planet Taco: A Global History of Mexican Food, 24-30. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Pilcher, Jeffrey M. “Tex-mex, Cal-mex, New Mex, or Whose Mex? Notes on the Historical Geography of Southwestern Cuisine.” Journal of the Southwest: 659–679.

- <http://www.jstor.org/stable/40170174> Web. 17 Nov. 2015.

Pilcher, Jeffrey M. "Was the Taco Invented in Southern California?." Gastronomica: 28-32.

Pilcher, Jeffrey M. “Who Chased Out the “Chili Queens”? Gender, Race, and Urban Reform in San Antonio, Texas, 1880–1943.” Taylor and Francis Online, 4 (Sep 2008): 173—200.

“The History of Taco.” Food Infographics. https://www.finedininglovers.com/blog/food-drinks/the-history-of-taco-food-infographic/ Web 17 Nov. 2015.