Mass Media on Mental Illness and Homelessness

Mass Media on Mental Illness and Homelessness

This page will examine through an intersectional feminist lens on how mental illness and homelessness is portrayed in mass media. Specifically I will be focusing on the region of Metro Vancouver and its homeless population.

Mental Illnesses in Canada

According to the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA), mental illness affects people of all ages, educational and income levels, and cultures. Furthermore mental illness indirectly affects all Canadians at some point through a relative, friend or colleague. Over 20% of Canadians will personally experience mental illness in their lifetime. [1].

What is Homelessness?

Previously people thought homelessness only affected a marginalized group of high-risk individuals. However since the 1980s this has changed, with rising rents and unemployment more people have become at risk for homelessness. Homelessness in Vancouver, Canada is a major social problem that has dramatically climbed over the past decade. According to the 2014 Metro Vancouver Homeless Count, over 2,770 people in Metro Vancouver were identified as homeless. In specific it accounted for 1,613 people in the sheltered homeless population, which includes people staying overnight in homeless shelters, transition houses, safe houses and people with no fixed addresses. Also it included a count of 957 people living outside or staying temporarily with others such as couch surfing. Overall the rise of homelessness in Vancouver has been linked to federal funding cuts to affordable housing in addition to the lack of a residual and stable income. However the aim of this page is to focus on the relationship between homelessness and mental health issues in Canada. Furthermore what is the role of the government in alleviating the problems related to mental health and homelessness? [2].

The Public Health of Canada says that “mental health is the capacity of each and all of us to feel, think and act in ways that enhance our ability to enjoy life and deal with the challenge we face”. Additionally it is described as “a positive sense of emotional and spiritual well-being that respects the importance of culture, equity, social justice, interconnections and personal dignity”. As illustrated by the CMHA, people with serious mental illness are more likely to be subject to the brinks of homelessness. Also many studies have shown that people who are homeless are more likely to experience compromised mental health and mental illness than the general population. Through years of research it has been found that people with mental illnesses are found to remain homeless for longer periods of time. There are several additional factors that can precede homelessness, with ties to the social determinants of health such as income difficulties and barriers to employment. In regards to patterns of mental health, a number of factors such as personal coping skills; perceived self-worth; one`s social environment; and other physical, cultural and socio-economic characteristics. It has been found that individuals with a stable and supported living environment are more likely to manage their mental illness and acquire adequate steps to their recovery. [3]. [4].

Homelessness in Metro Vancouver

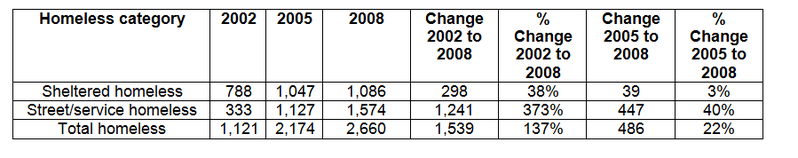

The issue of homelessness within the context of the Metro Vancouver region has been a point of continual concern and attention for over a decade. From 2002 to 2005, homelessness doubled, and grew by 22% from 2005 to 2008. The scope of the problem has become increasingly regional across Metro Vancouver over the past years, with 43% of the homeless population living in the region outside of the City of Vancouver. To eliminate or ameliorate the situation for the province’s homeless continues to be at the top of citizen survey priority lists, political campaign platforms, as well as provincial and municipal government funding priority lists, including and consequently, the subject persistently receives media attention. [5].

Case Study: The Riverview Hospital

In 1913, the Riverview Hospital, a mental health facility was opened in Coquitlam, British Columbia under the governance of BC Mental Health & Addiction Services. Initially it was open and housing over 340 male patients in its facilities. Over the next three years the patient population surpassed 680 people. Later in 1924, the hospital opened up its doors to house over 500 female patients. Eventually around 80 buildings were built in Riverview, which peaked in population of almost 5000 patients and around 2200 staff in 1955.

A big step was taken in Riverview in 1954 when the first time a psychiatric drug; chlorpromazine was used to treat in-patients. This replaced the former shock treatment therapy for severe depression and lobotomies for patients with schizophrenia, mania and psychotic disorders. The introduction of anti-psychotic drugs enlightened both patients and doctors with an understanding that mental illness was not untreatable. In 1965, a new BC Mental Health Act was passed, which encouraged the integration of locally operated mental health services. This led to the downsizing of Riverview, with the transfer of patients to areas closer to their home communities and support networks. By July 2012, the Riverview Hospital was permanently closed, which marked a significant end of institutional treatment and a shift towards community treatment. [6].

Potential Revival

There has been much talk about re-opening Riverview Hospital. In the wake of a housing crisis in Vancouver, and with mental illness being a major factor in homelessness, Riverview would be an excellent option to aid in alleviating some street homelessness.

In this Vancouver Sun article, Rich Coleman, B.C.'s housing minister, discusses plans to re-open parts of Riverview hospital as a mental health and addictions care facility.

Coquitlam Mayor Richard Stewarts, in a 2014 Global News article, “We just think that it’s very important to have a very solid mental health support presence on the site." The article states the reopening of the hospital is still up in the air, though the city's Mayor wholly supports the initiative. It's reopening is dependent on the involvement of higher levels of government and the residents of metro Vancouver.

Functions of the Media: Why Examine Media Representations of Homelessness?

Typically the public learns about people who are homeless through personal observation and through mass media. Whether a circumstance such as homelessness is even presented as a social problem, as something that needs addressing, can influence public opinion on actions and policy formation.

To understand the various media representations of homelessness, it is essential to begin with a brief introduction of the varying roles and functions of the mass media. It has been argued that the role of mass media can establish a way to encourage public and government attention to key issues such as homelessness, in addition to targeting the attention of politicians and policy-makers. Also, the role and influence of the media is based upon the media’s ability to increase the accessibility of information on any pertinent issue. Consequently, the people that have influence over policy-making, such as government departments, corporations, and many voluntary organizations, place importance on media coverage of an issue. Both the amount of coverage, as well as the nature of media attention shape and influence our attitudes and understanding of pertinent issues such as homelessness and mental illness. Our receptiveness to news broadcasts about homelessness has been found to be influenced by one’s personal status and beliefs, and any contact with homeless people themselves. Other factors that might influence receptiveness to media frames include social status, in relation to issues around housing, politics, and religions. In regards to television as a platform for mass media, the content and structure of news stories are correlated with the issues viewers consider important. Social policies influenced by politicians are often challenged if the society is unreceptive to them. On the other hand, mass media portrayals also reflect social norms. Furthermore, to what extent does mass media reflects the diverse values, beliefs and perceptions of homelessness? [7]. [8].

Understanding Media Representations of Homelessness in Metro Vancouver: A Study by Mary Ellen Glover

In a research study that aims to understand media representations of homelessness, Glover examines the ways in which regional newsprint media covered homelessness during a specific time period, January to June 2008, during which the goals of regional homeless stakeholders were to raise both public and media awareness of and attention to the problem of homelessness through an event, the 2008 Metro Vancouver Homeless Count. The focus of the 2008 Count was to increase the awareness of the problem of homelessness in Metro Vancouver to the attention of the public.

In the study, Glover uses comparative of news coverage leading up to, including, and following the 2008 Count. To achieve the underlying purpose of understanding media coverage of homelessness in Metro Vancouver, and the implications of this coverage, the current study is an assessment of the nature of the coverage, and the frames of the media attention. Glover discusses the implication of media attention on public attention to a particular societal problem. It is important to analyze the pattern of media coverage in order to understand how the public views certain issues such as homelessness. Public attention has the potential to influence a demand for response to the problem. Therefore the public commitment to solutions has the potential to impact political, and more importantly financial, commitments to the solutions. [10].

Mass Media and Homelessness: How is Homelessness Represented in Mass Media in Metro Vancouver?

Media representations of homelessness demonstrate the ways in which homelessness, and its causes and solutions, may have been traditionally understood by the general public, the media, as well as policy-makers. An analysis of newsprint media in Metro Vancouver portrays the causes and solutions to the region’s growing problem of homelessness. The findings address how the implications of some of the themes in media portrayals might be for those who are trying to increase public knowledge about the overarching causes and solutions to homelessness in the region. In order gain a further understanding of the issue, newsprint media coverage in the Metro Vancouver region was examined over 18 months, from 2007 to 2009. Content analysis methods assisted in finding the causes and solutions for homelessness, as outlined in the regional newsprint media coverage. An assessment of the Metro Vancouver newsprint media coverage enabled the examination of events, public sentiment and political environment surrounding homelessness in the Metro Vancouver region. Within regional newsprint coverage of homelessness, both short-term as well as longer term causes of and solution or responses to homelessness were covered. Major factors of influence, specifically addictions and mental illness were reported most often as primary causes of homelessness in the media coverage. Other factors included housing affordability, availability, housing conditions and costs. The role of municipal governments were referenced and documented most frequently with homelessness, in regional media coverage. Unfortunately a common finding in media reports was the lack of an overall common understanding of the causes of, and solutions to homelessness in Metro Vancouver. Over 10 regional media coverage of homelessness accurately reflected several existing trends in homelessness in Metro Vancouver, identified in 2008 Homeless Count.

Here are some links to articles discussing the 2008 Homeless Count:

- "Homeless numbers jump across Lower Mainland" By CTVBC http://bc.ctvnews.ca/homeless-numbers-jump-across-lower-mainland-1.287994

- "How to End Homelessness" By Monte Paulsen http://thetyee.ca/Views/2008/12/08/Solutions/

- "Metro Vancouver homeless count hides many" By Carlito Pablo http://www.straight.com/article-140217/homeless-count-hides-many

- "Homelessness: Keep up the fight for street people" By Cheryl Chan http://www.theprovince.com/life/Homelessness+Keep+fight+street+people/2463923/story.html

Media Coverage of Vancouver Homeless Count 2015

In 2008, Mayor Gregor pledged to end street homelessness by 2015 as one of his election goals. While he has taken small steps to achieve this goal, he has ultimately failed to reach it. Media coverage of the 2015 Homeless Count in Vancouver discusses Mayor Gregor's failure in a number of ways. Many also mention the need for mental health housing in order to adequately approach the issues at hand.

This Vancourier article discusses Gregor's failure, citing a gradual increase in homelessness since 2008. While the 2015 count has not yet been release, numbers from 2008 to 2014 rose from 1,576 to 1,803, demonstrating a massive failure despite attempts to make positive changes.

In this Global News article, Gregor mentions one of the factors in rising homelessness rates is a "lack of mental health support."

In this Georgia Straight article, Gregor talks about the steps he has taken to eliminate homelessness, namely new supportive housing buildings going up (like Taylor Manor). He says, "These are homes for some of our most vulnerable residents... I'm glad we've enabled homes for them."

What is being done to address the issues of homelessness and mental illness?

In 2008, the Government of Canada invested $110 million towards the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC) to conduct a research demonstration project on mental health and homelessness. This led to a four-year project in five cities in Canada with an aim to provide practical and discernible support to Canadians faced with homelessness and mental health issues. Subsequently the MHCC demonstrates, evaluates and shares knowledge about the efficiency of a “housing first” approach which addresses people that need a place to live. Also this approach offers recovery-oriented services and supports that cater to individual needs. [13].

The Granville Youth Health Centre

In 2015, a multi-million-dollar centre for street youth who are homeless or at risk of homelessness opened as a joint initiative between the Ministry of Health and St. Paul’s Hospital Foundation. The Granville Youth Health Centre aims to house the Inner City Youth team run by St. Paul’s Hospital since 2006 to service vulnerable youth under 24 years old experiencing mental illness and addiction. The team will provide integrated services such as primary care, counselling, therapy, psychiatric assessment, group recreational activities and independent living skills. The new centre, located on Granville Street, expects to service up to 1,200 clients by 2016 and facilitate 6,000 to 8,000 visits annually.

Taylor Manor

In 2015, Taylor Manor, a 56-unit supportive housing building for individuals experiencing mental illness and addictions was built. The City of Vancouver contributed the building, a 3-storey Tudor revival style mansion, a sum of $3.1 million from their 2013-14 Capital budget to launch the project, and an additional $323,000 in Capital building and grounds maintenance. Other funding efforts include a $10 million dollar contribution from the Government of Canada, $1.2 million donation from Vancity, and $1.4 million from streettohome , plus additional financial support from anonymous donors. [15].

Taylor Manor is run by The Kettle Friendship Society. It can house up to 56 residents, and is staffed, offering on-site support for residents with histories of mental illness and addiction. [15].

There are many mental health housing building like Taylor Manor. Organizations like Coast Mental Health, The Bloom Group, Raincity Housing, MPA Society, Lookout Society and BC Housing all provide supportive housing buildings for people experiencing mental illness or addictions.

The Representation of Homelessness and Mental Illness in Mass Media: Stop Motion Video

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oEm_XujsZ28&feature=youtu.be

References

- ↑ CMHA. Fast Facts about Mental Illness - Canadian Mental Health Association. Canadian Mental Health Association. CMHA, 2014. Web. 09 Feb. 2015. http://www.cmha.ca/media/fast-facts-about-mental-illness/#.VN6LWfnF98E

- ↑ About The 2014 Metro Vancouver Homeless Count. 2014 Metro Vancouver Homeless Count Preliminary Report Introduction (n.d.): n. pag. 2014 Metro Vancouver Homeless Count. StopHomelessness.ca, 23 Apr. 2014. Web. 9 Feb. 2015. http://stophomelessness.ca/wp-content/uploads/2008/09/Preliminary_release_report_final_April_23_14_to_be_posted.pdf

- ↑ Mowbray, Carol T. Mental Health and Mental Illness: Out of the Closet. Social Service Review 76.1, 75th Anniversary Issue (2002): 135-79. Cities Centre U of T, 2009. Web. 09 Feb. 2015. http://homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/2.3%20CPHI%20Mental%20Health%20Mental%20Illness%20and%20Homelessness.pdf

- ↑ CMHA. Homelessness - Canadian Mental Health Association.Canadian Mental Health Association. CMHA, 2014. Web. 9 Feb. 2015. http://www.cmha.ca/public-policy/subject/homelessness/

- ↑ Glover, Mary Ellen. "Understanding media representations of homelessness in Metro Vancouver." SFU Master of Urban Studies (2010): 1-145. Web. 9 Feb. 2015. http://summit.sfu.ca/item/11492

- ↑ Hall, Neal. "Closure of Riverview Hospital Marks End of Era in Mental Health Treatment." Vancouver Sun. Vancouver Sun, 20 July 2012. Web. 9 Feb. 2015. http://www.vancouversun.com/health/Closure+Riverview+Hospital+marks+mental+health+treatment/6967310/story.html

- ↑ Glover, Mary Ellen. "Understanding media representations of homelessness in Metro Vancouver." SFU Master of Urban Studies (2010): 1-145. Web. 9 Feb. 2015. http://summit.sfu.ca/item/11492

- ↑ Mao, Yuping, et al. "Framing Homelessness for the Canadian Public: The News Media and Homelessness." Canadian Journal of Urban Research 20.2 (2011): 1-20. Web. 9 Feb. 2015. http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/1023234848?accountid=14656

- ↑ Newton, Robyn. “2008 Metro Vancouver Homeless Count” Greater Vancouver Regional Steering Committee on Homelessness (2008): 1-64.. Web. 9 Feb. 2015. http://www.metrovancouver.org/services/regional-planning/homelessness/HomelessnessPublications/HomelessCountReport2008Feb12.pdf

- ↑ Glover, Mary Ellen. "Understanding media representations of homelessness in Metro Vancouver." SFU Master of Urban Studies (2010): 1-145. Web. 9 Feb. 2015. http://summit.sfu.ca/item/11492

- ↑ Glover, Mary Ellen. "Understanding media representations of homelessness in Metro Vancouver." SFU Master of Urban Studies (2010): 1-145. Web. 9 Feb. 2015. http://summit.sfu.ca/item/11492

- ↑ Mao, Yuping, et al. "Framing Homelessness for the Canadian Public: The News Media and Homelessness." Canadian Journal of Urban Research 20.2 (2011): 1-20. Web. 9 Feb. 2015. http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/1023234848?accountid=14656

- ↑ Initiatives: At Home.Mental Health Commission of Canada. MHCC, 2012. Web. 9 Feb. 2015. http://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/English/initiatives-and-projects/home?routetoken=569978849859f0649130463ac3036ae8&terminitial=38

- ↑ Global News, BC. "Granville Health Centre." Providence Health Care. 13 Mar. 2015. Web. http://www.providencehealthcare.org/news/20150318/granville-health-centre-aimed-helping-youth-inner-city-youth-program-st-pauls-hospital

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 The Kettle's Taylor Manor Opens! The Kettle Friendship Society. N.p., 19 Mar. 2015. Web.

Citations

About The 2014 Metro Vancouver Homeless Count. 2014 Metro Vancouver Homeless Count Preliminary Report Introduction (n.d.): n. pag. 2014 Metro Vancouver Homeless Count. StopHomelessness.ca, 23 Apr. 2014. Web. 9 Mar. 2015.

Canadian Observatory on Homelessness. “Canadian Definition of Homelessness.” Homeless Hub (2012): 1-5. Web.

CMHA. Fast Facts about Mental Illness - Canadian Mental Health Association. Canadian Mental Health Association. CMHA, 2014. Web. 09 Mar. 2015.

Global News, BC. "Granville Health Centre." Providence Health Care. 13 Mar. 2015. Web.

Glover, Mary Ellen. "Understanding media representations of homelessness in Metro Vancouver."SFU Master of Urban Studies (2010): 1-145. 13 Mar. 2015. Web.

Hall, Neal. "Closure of Riverview Hospital Marks End of Era in Mental Health Treatment." Vancouver Sun. Vancouver Sun, 20 July 2012. Web. 9 Mar. 2015.

Hwang, Stephen W. “Homelessness and Health.” CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal 164.2 (2001): 229–233. Web.

Newton, Robyn. “2008 Metro Vancouver Homeless Count” Greater Vancouver Regional Steering Committee on Homelessness (2008): 1-64.. Web. 9 Feb. 2015

Mowbray, Carol T. Mental Health and Mental Illness: Out of the Closet. Social Service Review 76.1, 75th Anniversary Issue (2002): 135-79. Cities Centre U of T, 2009. Web. 09 Feb. 2015.

Piat, Myra, Jayne Barker, and Paula Goering. "A major Canadian initiative to address mental health and homelessness." CJNR (Canadian Journal of Nursing Research) 41.2 (2009): 79-82. Web.

Piat, Myra, et al. "Pathways into homelessness: Understanding how both individual and structural factors contribute to and sustain homelessness in Canada." Urban Studies (2014): 1-17. Web.

Sullivan, Greer, Audrey Burnam, and Paul Koegel. "Pathways to homelessness among the mentally ill." Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology 35.10 (2000): 444-450. Web.