Guidelines for Effective Writing- Writing Process/Organizing/Paragraph Structure, Topic Sentences, Transitions

Paragraph Structure, Topic Sentences and Transitions

Even the most well-researched piece of science writing will fail to make an impact if it is not easy to read and interpret. The trick to organizing your writing is to develop a writing outline before you put pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard). More information on outlines can be found on our outlining resource.

There are three key things that you can focus on to make sure that your writing is well organized. Firstly, you can split it into paragraphs based on content. Secondly, you can write effective topic sentences to kick off each paragraph with, and thirdly, you can ensure each sentence flows smoothly into the next by making sure your transitions are well chosen.

Paragraphs

Paragraphs are extremely important components of an effectively structured piece of writing because they organize material in a way that makes it easier to follow for your readers. Structuring your writing into clear, effective paragraphs that address individual ideas will help you organize your work, which in turn gives your readers the best possible chance of understanding the points you are trying to make.

Here are some strategies for writing clear paragraphs:

- Have a clear topic sentence. Make sure that the first sentence of your paragraph clearly captures the main point of your paragraph. This establishes the topic of the paragraph and sets up the readers expectations.

- Provide evidence to fully support the main point. Each sentence in the paragraph should expand upon or support the topic sentence.

- The relationship between the topic sentence and the concluding sentence should be clear. If not, it is possible that the purpose of the paragraph may have changed midway through. If this happens, consider rewriting the topic sentence to reflect what the paragraph actually does, or breaking the paragraph into smaller parts.

Topic Sentences

An effective topic sentence should begin each new paragraph by informing your reader what the upcoming paragraph is about, and it should also link the flow of your argument from the previous paragraph to the current one. The key is to be specific enough so that a reader knows exactly what to expect, and which direction your writing is heading in, without being so specific that it only applies to part of the paragraph.

As a rough indicator of whether you have written clear topic sentences, a reader in a real hurry should be able to read these, and these only (i.e. avoid the detailed information in all the paragraphs), and still be able to understand the backbone of the argument you are making. You can do this yourself, when you have finished writing, as a guide to see whether your writing flows smoothly and follows a logical path.

Some Examples (errors and improvements)

A1 (topic sentence missing):

“When cornered by a pack of wolves, even the most terrified hare will run within the closing circle, desperately seeking an escape route. Fish caught in a trawler net will swim round and round, looking for a way out. Even primitive micro-organisms will move as far away as possible from a negative stimulus, somehow conditioned to flee from impending death.”

B1 (with effective topic sentence):

“There is a huge diversity of life on earth, but all organisms display a common desire to survive. When cornered by a pack of wolves, even the most terrified hare will run within the closing circle, desperately seeking an escape route. Fish caught in a trawler net will swim round and round, looking for a way out. Even primitive micro-organisms will move as far away as possible from a negative stimulus, somehow conditioned to flee from impending death.”

A2 (topic sentence does not relate closely enough to paragraph):

“There is a huge diversity of life on earth, but all organisms display a common desire to survive. When cornered by a pack of wolves, even the most terrified hare will run within the closing circle, desperately seeking an escape route. Wolves co-ordinate their hunting efforts so as to increase their chances of catching prey, but those with higher social ranks earn the right to eat before their inferiors. Hares, on the other hand, typically forage for food on their own. Although they do not benefit from the increased awareness of where food might be, which would come from searching with others, they never have to share their food when they find it.”

B2 (topic sentence relates directly to paragraph):

“Wolves and hares use different foraging strategies, and there are positives and negatives associated with each. Wolves co-ordinate their hunting efforts so as to increase their chances of catching prey, but food must be shared and wolves with higher social ranks earn the right to eat before their inferiors. Hares, on the other hand, typically forage for food on their own. Although they do not benefit from the increased awareness of where food might be, which would come from searching with others, they never have to share their food when they find it.”

Transitions

a) Have a clear topic sentence. Make sure that the first sentence of your paragraph clearly captures the main point of your paragraph. This establishes the topic of the paragraph and sets up the reader's expectations.

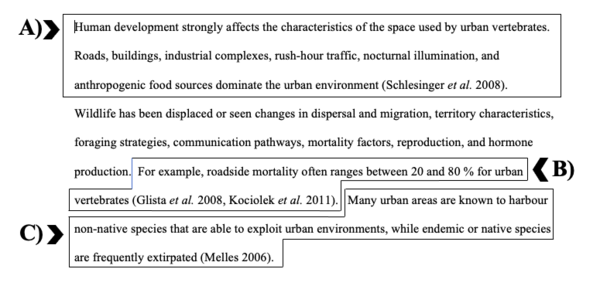

- In the example excerpted from Garber (2012) below, the first sentence of the paragraph is the topic sentence. This sentence clearly introduces the topic and establishes what is going to be discussed throughout the paragraph (i.e., how human development impacts various aspects of the environment that “urban vertebrates” use.)

b) Provide evidence to fully support the main point. Each sentence in the paragraph should expand upon or support the topic sentence.

- In the excerpt below, the author uses an example to provide concrete evidence to support the main point of the paragraph.

c) The relationship between the topic sentence and the concluding sentence should be clear. If not, it is possible that the purpose of the paragraph may have changed midway through. If this happens, consider rewriting the topic sentence to reflect what the paragraph actually does, or breaking the paragraph into smaller parts

- In the particular example below, the author concludes the paragraph by clearly connecting back to and emphasizing the initial point in the first sentence.

Figure 1. Adapted from Philipp Garber, Urban Vertebrate Ecology of the Pacific Northwest, with Recommendations for Wildlife Stewardship at UBC Vancouver (Vancouver: University of British Columbia, 2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0108522.

An Example

A1 (Poor transitions): “Global warming will have negative consequences for polar bears. As temperatures rise they will have a smaller habitat in which to live. Also, there will be less food available for them because there will be smaller populations of krill. Polar bear populations are thus affected by the amount of ice available.”

B1 (Good transitions): “Global warming will have negative consequences for polar bears for two main reasons. Firstly, because increased temperatures cause increased melting of ice on which the bears live, there will be a reduced area in which they can live. Secondly, many species that polar bears rely on for food will be less numerous than in the past because their main food source, krill, can only breed successfully underneath ice. Therefore, the reduction of ice is the key factor in limiting polar bear populations.”

B1 is better than A1 because:

- Each transition informs the reader that a new idea is about to be elaborated on

- Each sentence begins with a ‘signpost’ that links it to the next one

- Each transition connects the points made in the whole text with one another