GRSJ224/socialconstructionofillness

Overview

The social construction of illness is a pertinent theoretical perspective in medical sociology. Although individuals are exclusively responsible for their actions and held accountable for whatever consequences they may reap, from a sociological perspective, the said actions do not arise in a ‘social vacuum’, and need to be understood within the social context. This way, we take into consideration the cultural patterns and social forces that put pressure on people to select one choice over another. It is also important to emphasize how social constructionism provides a crucial contradiction to medicine's largely prevalent approaches to disease and illness.

The Origins of Social Constructionism

The social construction of illness has become a fundamental research concept in the subfield of biomedicine in the last 50 years. Social constructionism is a framework signifies the cultural and historical aspects of a concept that is widely thought to be singularly natural. The emphasis is on how meanings of phenomena do not undoubtedly reside in the phenomena themselves but develop through interaction in a social context. To phrase it another way, social constructionism analyzes how individuals and groups contribute to producing a socially perceived reality and knowledge. [1] Regardless of the plethora of attacks and shortcomings of the differentiation between the strictly biological definition of disease and illness (the social meaning of the condition), it is nevertheless an exceedingly useful conceptual tool. [2]

Symbolic Interactionism and Phenomenology

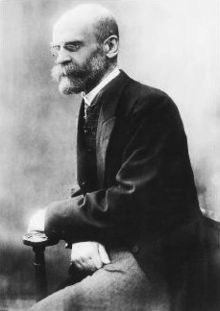

Symbolic interactionism and phenomenology are two widely renown and encroaching trends in sociology established in the 1960s. They also significantly contributed to a social constructionist approach to illness. Erving Goffman’s[3] preceding work helped to build the foundation for the symbolic interactionist tradition. Through his conceptualization of the “moral career,”[3] Goffman spoke to the social experiences of patient-hood, as distinct from any biological condition that may or may not instigate an aforementioned career. According to Goffman and other symbolic interactionists of the like, individuals actively participate in the development of their own social worlds, including the construction of the self through the utilization of various interactions within their proximal environments.[4] The main principles of symbolic interactionism effectively led to a detailed exploration of illness as experienced within confounds of daily social interactions, which in turn transform the performance of self. [5][6] This is by no means a comprehensive account of the social constructionist approach to illness. Moreover, it is not mutually exclusive. Many medical sociologists draw on various aspects of these different traditions. They consider the social construction of illness approach as something of an amalgamation. Although this diminishes important differences between various types of social constructionism, it can be justified in that they all share a rejection of a strictly positivist conception of illness as the mere embodiment of disease. The approach determines how illness is shaped by social interdependence, shared cultural values, growing advances of knowledge, and relations of power.

Gender

The gender context of illnesses and disabilities is an inherent part of the social constructionist point of view. For feminists who study health and illness, attention to gender has meant concern with the status of women and men in the social order. Feminists have expressed their frustration with how such normal physiological events as menstruation and menopause have been turned into illnesses and consequently into social problems. From a social construction perspective, gender is a society's division of people into differentiated categories of "women" and "men". Gender divisions are built into the major social organizations of societies, such as the economy, the family, religion, the arts, and politics. In those societies, gender is a major social status for individuals, with established patterns of expectations and life opportunities. The social construction perspective sees gendering as an ongoing process - with people constantly "doing gender".[7]

Conclusion

Studies on medicalization and biomedicine will continue to be an integral subject of research in the social constructionist arena. First, some illnesses are particularly embedded with underlying cultural meaning that shapes how society responds to those afflicted and influences the experience of that illness. Second, all illnesses are socially constructed at a practical level based on how individuals come to understand their illness, produce their identity, and live with and in spite of their illness. Third, as feminist and medicalization analysts have demonstrated, medical knowledge about disease is not necessarily objectively given in nature; rather, it is constructed and developed by affected parties who frequently have strong evaluative criteria. These findings do not invalidate scientific and medical perspectives, but rather demonstrate that diseases and illnesses are as much social products as medical-scientific ones.

References

- ↑ Berger, Peter and Thomas Luckmann. 1966. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. New York: Anchor.

- ↑ Timmermans, Stephan and Steven Haas. 2008. “Towards a Sociology of Disease.” Sociology of Health and Ill- ness 30:659–76.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Goffman, Erving. 1961. Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. Gar- den City, NJ: Doubleday.

- ↑ Blumer, Herbert. 1969. Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- ↑ Charmaz, Kathy. 1991. Good Days, Bad Days: The Self in Chronic Illness and Time. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- ↑ Glaser, Barney G. and Anselm C. Strauss. 1965. Aware- ness of Dying. Chicago, IL: Aldine Transaction.

- ↑ West, C. and D. H. Zimmerman. "Doing Gender". Gender & Society 1.2 (1987): 125-151.