GRSJ224 Colonialism of Northern British Columbia and it's Effects on First Nations

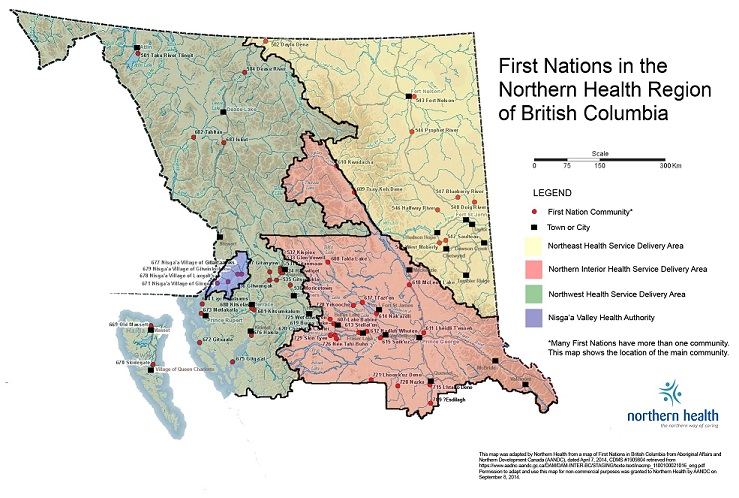

Colonialism in Northern British Columbia focuses on the settlement of the Northern region of British Columbia, a province within Canada, and the practices and effects this settlement had on the First Nations of this region. British Columbia is home to 198 First Nations groups, approximately one third of all First Nations across Canada.[1] over 35 per cent of BC's First Nation population lives in the Northern region.[2]This high proportion of First Nations within British Columbia provides the province with a rich diversity of Aboriginal traditions and histories and is the home to 7 out of 11 of Canada's unique languages.[3]

The Aboriginal Communities in the Northern region of British Columbia have inhabited the territory for over 10 000 years, hunting and berry picking during the summers and trapping during the winters.[4] Today, using the Northern Health's coverage regions, there are 8 First Nations communities in the Northeast region, 22 in the Northern Interior, and 25 in the Northwest region of British Columbia.[5]

===== First Nations Reserves In Northern British Columbia =====

| Northwest | Northern Interior | Northeast | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dease River | Gingolx | Esdilagh | Kwadacha | Blueberry River |

| Gitanyow | Gitaxaala | Lhoosk'uz | Nak'azdli | Fort Nelson |

| Gitga'at | Kitamaat | Red Bluff | Stellat'en | Saulteau |

| Hagwilget | Metlakatla | Tsay Keh Dene | Burns lake | Daylu Dena |

| Wet'suwet'en | Taki River Tlingit | Lake Babine | McLeod Lake | Halfway River |

| Sik-e-dakh | Kispoix | Nazko | Saik'uz | West Moberly |

| New Aiyansh | Gitwinksihlkw | Takla Lake | Wet'suwet'en | Doig River |

| Gingolx | Gitsegukla | Cheslatta Carrier | Yekooche | Prophet River |

| Gitwangak | Iskut | Lheidli T'enneh | ||

| Kitselas | Lazgalts'ap | Nadleh Whut'en | ||

| Moricetown | Old Massett | Nee Tahi Buhn | ||

| Gitanmaax | Kitsumkalum | Skin Tyee | ||

| Lax Kw'alaams | Skidegate | Tl'azt'en |

Colonialism Of Northern British Columbia

Grand Trunk Pacific Railway

The Grand Trunk Pacific Railway was the transcontinental railway that ran from Winnipeg, Manitoba to Prince Rupert, British Columbia[6]. In 1908 the railway identified the Lheidli T'enneh Fort George Reserve, nestled in the junction of the Fraser and Nechako rivers, as the desired location for a railway terminal.[7] This Lheidli T'enneh reserve was established in 1892 by Peter O'Reilly who determined the land agriculturally worthless and far enough away that it wouldn't impede on progress of the country.[8]

Plans to purchase the Reserve lands began when the railway's Chief Engineer B.B. Kelliher reported the land vacant.[9] D'Arcy Tate, the railway's assistant solicitor, hoped to purchase the 1,366 acres for $3,415.[10] The Department of Indian affairs turned down three other offers for the land between 1908 and 1910 which included the preservation of the Band's traditional cemetery and a $500 lifetime payout to the residents. [11] November 18, 1911 the Band made a surrender vote with the revised agreement of $100,000 and $25,000 to construct new buildings on the new reserve location as well as preservation of the burial ground. [12] After delays in construction and payments, along with the deduction of $4,000 to cover construction overruns resulting from contracts organized by the Department of Indian Affairs, the Lheidli T'enneh people relocated September 1913 to what is now known as the Shelly Reserve.[13] After the band relocated, their village was burned to the ground to avoid re-entry.[14].

Reserve 172

April 11, 1916 the Beaver band moved to the 18,168 acres of land seven miles from Fort St. John as negotiated in the Treaty 8 negotiations.[15] This land 'Suu Na Chii K' Chi De', 'Where Happiness Dwells' became reserve 172.[16] According to the correspondence of the Department of Indian Affairs, between 1933 and 1944 the surrender of this newly formed reserve was negotiated. Starting in 1933 with Lester B. Reid, the Secretary of the Board of Trade for Rose Prairie, requested the settlement of the reserve 172 lands. Reid's remarks in the proposal reflect the colonial atmosphere of the time. The Secretary proclaims that the First Nations band's only use for the land was to receive treaty money, disregarding the ceremonial significance to the band. Reid's focused instead on how the land would be used to advance the colonialist principles of domination over nature.[17] Mindy Christianson, inspector for Alberta and Northern British Columbia for the Department of Indian Affairs, rejected the proposal on the grounds that the Beaver people had already been relocated and thus needed to be protected.[18]

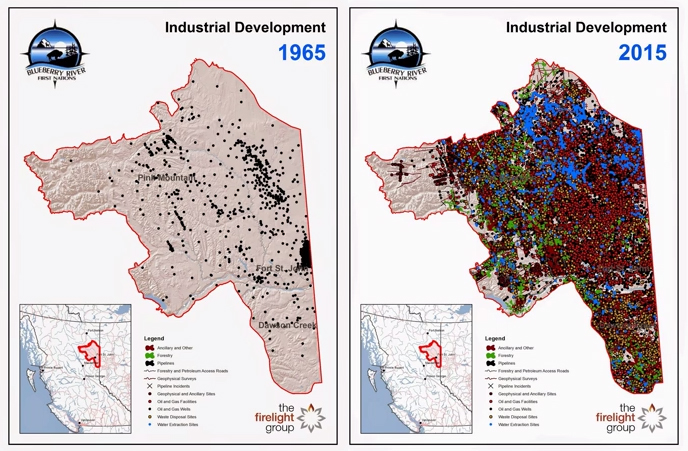

Dr. Hubert Aruthur Woods Brown, the local Indian agent between 1934 and 1945, was a strong supporter of industrial and agricultural development. As these interests increased in the region, in 1940 Brown, at the request of R.M. Steel, the petroleum engineer for the Department of Mines and Resources, executed the surrender of mineral rights of the Beaver Bands to the Government of Canada "in trust to lease"[19].[20] This was ultimately a significant step towards the complete surrender of Reserve 172. Spring of 2015 the Blueberry River First Nations, decedents of the Beaver band, launched a $7.5 million lawsuit against gas development arguing that their rights according the Treaty 8 have been breached as a result of continued industrial development within their traditional territory.[21]

C. Pant Schmidt replaced Christianson in 1936 and remained the Department of Indian Affairs Regional Inspector for the region until 1946.[22] Schmidt filed two comprehensive reports between 1941 and 1943 questioning the Band's behavior while suggesting intervention and childcare through residential schools.[23] Shortly after, on September 22, 1945 the surrender of Reserve 172 was processed. Despite claims by witnesses[24] that the agreement was signed without casting of individual votes, Chief Succona reported a majority in favor for the surrender and released the land "in trust to sell of lease upon such terms as the government of Canada may deem most conductive to the welfare of the band."[25] [26] The Beaver people were then relocated to land on the Blueberry and Beaton Rivers. 1948 Reserve 172 was sold to the Department of Veterans' Affairs for less than the appraised value, and in 1949, oil and gas was discovered.[27]

Bureaucratic Paternalism

Aboriginal populations of British Columbia, as well as across Canada, have been fighting to overcome the negative consequences of the Euro-Colonial beliefs and practices thrust upon them during settlement. The belief that non-euro peoples and all elements of their existence was flawed and inferior fostered the creation of structures and practices that stripped Aboriginals of their nation and nationhood.[28]

The Colonial interactions with Aboriginal populations were based on the racist assumptions of Aboriginal inferiority and the belief that their ‘savage’ behaviour was the antagonist to European civility. [29] Many Aboriginal practices were seen to be in conflict with the Colonialist ideals of the time. Progress was advertised to be a heroic assignment and with it the domination and taming of wild lands. Colonial settlers saw the land used by the First Nations population as wasted, not recognizing the historical and cultural significance. [30] This paired with the belief that First Nations were poverty, disease stricken 'savages' was the ‘Indian Problem’ thought to be only solved through bureaucratic paternalism. This was the management of Aboriginal populations through the implementation of laws, policies, and institutions that would act in the 'best interest' of Aboriginal population according to the Colonial state. [31] Bureaucratic Paternalism operated in First Nations Residential Schools and the formation of the Indian act.

The relocation of reserves like those of the Lheidli T'enneh and the Beaver Reserve 172 were legitimized by the argument that relocation away from White settlements was in the best interest for Aboriginal groups as they could be sheltered by missionary groups and the Department of Indian Affairs. [32] This 'duty of protection' believed to be the moral responsibility of the Department of Indian Affairs reflects this belief in Aboriginal disparity and need for exterior governance. Under legislation like the Indian Act, First Nations were considered wards of the state who needed assistance to meet the colonial standards of living. This assistance was in the form of forced intervention and assimilation. Legislation created through the policy of bureaucratic paternalism has continued to restrict Aboriginal communities from self-governance, land claims, and economic development with lasting consequences on social, economic and health status.[33]

Residential Schools

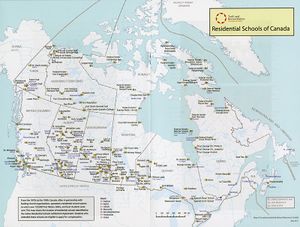

Residential Schools were created by the ideology that Euro-Colonists were superior to all other non-European cultures. This forced colonial education was present in Canada's first Aboriginal boarding school established in 1620 in New France by the Rècollects.[34]

Although this process of forced colonial education was outlined in the Indian Act, these institutions were fully erected after Nicolas Flood Davin's report Industrial Schools for Indians and Half-Breeds (Canada, 1879)[35]. Davin explained that with continued interaction to their families and cultures, students would revert back to their 'savage' ways and that the only way to ensure their 'success' in Colonial society would be to eliminate these influences. It was then that this method of institutionalized assimilation and racism swept across the country.

Within the boarders of British Columbia there were 18 Residential schools in operation between 1861 and 1984. Of these 18 schools 4 were operational in the northern region of British Columbia. These schools include Port Simpson, Metlakatla, Elizabeth Long Memorial Home , and Lejac. The schools focused on Christianization of Aboriginal students, fluency in English or French, training in trades, agriculture and domestic duties as well as the overall indoctrination of European values and morals. [36]

The effects of the forceful removal of Aboriginal students from their families and homes are well documented today. The inter-generational effects of a generation of children dislodged from all that they know and subjected to sexual violence, humiliation, and personal degradation can be seen in current social, economic and health statistics of Aboriginal populations across Canada.

Effects of Colonialism

Through the process of colonization, much of the traditional territories of First Nation populations have become the sites of large urban settlement. These settlements, although able to provide a variety of services, maintain many barriers to aboriginal populations. The 2001 Census shows that 49% of Aboriginal populations live within cities and this trend is increasing.[37] Aboriginal populations are in a worse position than non-Aboriginal populations in all social and economic indicators including high rates of homelessness, unemployment, poverty, crime, lower levels of education and higher health related problems[38]

Prince George

Prince George with a population of 71,973, is the largest city in the Northern region of British Columbia. The percentage of population that identify as Aboriginal is the highest in the province at 12% and second in Canada only to Prince Albert, Saskatchewan at 25.8%. Looking at the statistics for Prince George's Aboriginal population it becomes clear that there are existing barriers. In 2011, 28.4% of the total Aboriginal population was under 14 years of age.[39] Of these children, 39.5% lived in lone-parent families, 83.3% being single mothers.[40] 56.8% of Aboriginals made less than $20,000 in 2010, 61.9% of this population were female.

Prince George's crime rate has been decreasing and the city has lost its title as the 'most dangerous city in Canada'; however, there has clearly been a history of increased crime within that region. Most of the crime that has given Prince George its title has been gang and drug related.[41] The percentage of the Aboriginal population living at or below the poverty line likely has an impact on crime rates. This has been associated with the high rates of unemployment and dependency on social assistance payments resulting from the colonial practice of Bureaucratic paternalism.

Health

The high mobility of Aboriginal populations makes access and provision of adequate healthcare difficult. The most common reasons for this mobility are family motives and the search for better jobs and housing. A current crisis for Urban Aboriginal populations include very high rates of AIDS/HIV and Hep C, especially among women.[42] In addition, the top health concerns according to Aboriginal women include diabetes, mental health, liver cancer, hypertension, substance abuse, and obesity.[43] Most of the resources needed to address these concerns cannot be accessed in rural communities and especially not on reserves, which contributes to the large influx of Aboriginals to urban centers.

Education

According to Statistics Canada in 2011, 35.3% of the Aboriginal population in Prince George age 15 years or older had no education certification or high school diploma and only 34.5% had some form of post-secondary education. [44] This is very low compared to the general population with post-secondary rates of nearly 50%. [45] Nationally, 8 out of 10 aboriginal youth drop out of high school.[46] Reasons for not attending school include: poverty; racism; lack of parental involvement; resentment caused by feeling less successful scholastically than other students; high rates of residential mobility; inability to afford textbooks, sporting equipment, or excursion fees; unstable home life; damaging effects of residential schools on Aboriginal peoples, cultures, and languages.[47] It is apparent that changes need to be made to the education system in order to ensure that the aboriginal youth have the same opportunities for education as does the general public. The National Aboriginal Health Organization has included a list of actions that are needed to improve aboriginal educational outcomes.

This list includes:

- The need to recruit and train more aboriginal teachers and staff

- Cross cultural sensitivity training for non-aboriginal teachers and staff

- Culturally-sensitive learning environments with culturally-appropriate curriculum development with knowledge of aboriginal languages and traditions necessary for cultural continuity

- Development of urban aboriginal schools

- And secondary school supports and guidance for aboriginal youth. .[48]

References

- ↑ Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (2010). About British Colombian First Nations. Retrieved from https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100021009/1314809450456

- ↑ Aboriginal Health. (2015). An Overview of First Nations Health Governance in Northern British Columbia. Prince George, BC: Northern. Retrieved from Health.https://northernhealth.ca/Portals/0/Your_Health/Programs/Aboriginal_Health/documents/Fact%20Sheet%20-%20Governance_web.pdf

- ↑ Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (2010). About British Columbia First Nations. Retrieved from https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100021009/1314809450456

- ↑ Roe, S. (2003) ‘IF the Story Could Be Heard’: 1 Colonial Discourse and the Surrender of Indian Reserve 172. BC Studies. 138/139. Pp. 115-136. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/196869440/fulltext/94FD6B1FC96D42B3PQ/1?accountid=14656

- ↑ Northern Health. First Nations and Aboriginal Communities in Northern B.C. Retrieved from https://northernhealth.ca/YourHealth/AboriginalHealth/FirstNationsAboriginalCommunitiesinNorthernBC.aspx

- ↑ Vogt, D. & Gamble, D. A. (2010) “You Don’t Suppose that Dominion Government Whats to Cheat the Indians?”: the Grand truck pacific railway and the fort George reserve, 1908-1912. BC Studies, 166 pp. 55-72. Retrieved from https://9hzqqa.bn1301.livefilestore.com/y3mPAdLbaRlT7yjNMQFH_vumbnwfvj93PxpK4Q9dpehVY-PXd1VGUUrgfzti2SmPhDXSnJBQg15X91Nr8gl1IdMsfztgsB0YwC8J9v8E-7mDK_w6PF72xkMC3CI3wJ9S0uNxStF3KGAFVkZ09q_NNOJfQ/Prince%20george%20and%20Lheidli.pdf?psid=1

- ↑ ibid

- ↑ ibid

- ↑ ibid

- ↑ ipid

- ↑ ibid

- ↑ ibid

- ↑ ibid

- ↑ ibid

- ↑ Roe, S. (2003)

- ↑ ibid

- ↑ ibid

- ↑ ibid

- ↑ Doig River First Nations (2007) Timeline: Treaty No. 8 and our Reserve Land Rights. Virtual museum. Retrieved from http://www.virtualmuseum.ca/sgc-cms/expositions-exhibitions/danewajich/english/places/montney_timeline.php

- ↑ Appellants' Excerpts on Appeal, vols. 1-4, Re Joseph Apsassin & Jerry Attachiez. The Queen, Federal Court of Canada, Trial Division. No. T-4178-87. Court File No. A-1240-87.

- ↑ Stodalka, W. (2015) In Northeastern B.C., one lawsuit that could change everything: Blueberry River First Nations wants industrial development 'suspended in our critical areas". Alaska Highway News. http://www.alaskahighwaynews.ca/regional-news/in-northeastern-b-c-one-lawsuit-that-could-change-everything-1.1788728

- ↑ Roe, S. (2003)

- ↑ ibid

- ↑ Beaver testimonies present a different image of DIA personnel in this time period, but it is difficult to distinguish between Brown, Grew, and Gallibois in the existing records. John Davis, a Beaver elder, testified that "the Indian Boss ... never help[ed] Indians" and that discussions included unrealized promises about "lots of money." "The "Boss" to whom Davis referred was Joe Gallibois. Cited in Ridmgton, "Cultures in Conflict," 282-3.

- ↑ Roe, S. (2003)

- ↑ Appellants' Excerpts on Appeal, vols. 1-4, Re Joseph Apsassin & Jerry Attachiez. The Queen, Federal Court of Canada, Trial Division. No. T-4178-87. Court File No. A-1240-87

- ↑ Roe, S. (2003)

- ↑ De Leeuw, S. (2007) Intimate Colonialism: the material and experienced places of British Columbia’s residential schools. The Canadian Geographer. 51(3) 339-359. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/doi/10.1111/j.1541-0064.2007.00183.x/abstract

- ↑ ibid

- ↑ ibid

- ↑ ibid

- ↑ Vogt, D. & Gamble, D. A. (2010) “You Don’t Suppose that Dominion Government Whats to Cheat the Indians?”: the Grand Truck Pacific Railway and the Fort George reserve, 1908-1912. BC Studies, 166 pp. 55-72. https://9hzqqa.bn1301.livefilestore.com/y3mPAdLbaRlT7yjNMQFH_vumbnwfvj93PxpK4Q9dpehVY-PXd1VGUUrgfzti2SmPhDXSnJBQg15X91Nr8gl1IdMsfztgsB0YwC8J9v8E-7mDK_w6PF72xkMC3CI3wJ9S0uNxStF3KGAFVkZ09q_NNOJfQ/Prince%20george%20and%20Lheidli.pdf?psid=1

- ↑ Browne, A.J., McDonald, H., & Elliott, D. (2009). First Nations Urban Aboriginal Health Research Discussion Paper, A Report for the First Nations Centre, National Aboriginal Health Organization. Ottawa, ON: National Aboriginal Organization. Retrieved from http://www.naho.ca/documents/fnc/english/UrbanFirstNationsHealthResearchDiscussionPaper.pdf

- ↑ De Leeuw, S. (2007)

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ ibid

- ↑ Carter, T. & Polevychok, C. (2004)Literature Review on Issues and Needs of Aboriginal people: to support work on ‘scoping’ research on issues for municipal governments and aboriginal people living within their boundaries

- ↑ Browne, A.J., McDonald, H., & Elliott, D. (2009)

- ↑ Statistics Canada (2011) National Household Survey. Aboriginal Population Profile, Prince George, CY, British Columbia, 2011. Retrieved from https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/dp-pd/aprof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=CSD&Code1=5953023&Data=Count&SearchText=prince%20george&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&A1=All&Custom=&TABID=1

- ↑ ibid

- ↑ Macqueen, K. & Treble, P. (2011) Canada's most dangerous city: Prince George. Macleans. Retrieved from http://www.macleans.ca/news/canada/crime-most-dangerous-cities/

- ↑ Browne, A.J., McDonald, H., & Elliott, D. (2009)

- ↑ Carter, T. & Polevychok, C. (2004)

- ↑ Statistics Canada (2011)

- ↑ Statistics Canada (2011) National Household Survey Profile, Prince George, CA, British Columbia, 2011. Retrieved from https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=CMA&Code1=970&Data=Count&SearchText=Prince%20George&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&A1=All&B1=All&Custom=&TABID=1

- ↑ Carter, T. & Polevychok, C. (2004)

- ↑ Browne, A.J., McDonald, H., & Elliott, D. (2009)

- ↑ Browne, A.J., McDonald, H., & Elliott, D. (2009)