Eurocentrism in Visual Art

Introduction

What is Eurocentrism?

Eurocentrism is derived from the word Eurocentric, defined as reflecting a tendency to interpret the world in terms of European or Anglo-American values and experiences. [1] In the context of visual art and theory, Eurocentrism is the hegemony, or dominance, of a European/Westernized culture as a universal value applied to other cultures (outside of European and Western). [2]

Brief History and Effects of Eurocentrism in First Nations

The concept of Eurocentrism came about in the period of decolonization in the 1960s and 1970s, decolonization being, as Oxford English Dictionary defines, as "the withdrawal from its colonies of a colonial power".[4]. It was not only referring to the withdrawal from colonial powers, but also reflected the attempt at the removal of domination of colonial powers on indigenous and minority groups, and thus on their culture. What Gerardo Mosquera has said about Eurocentrism is that the problem with it is that it is rooted in colonialism, something that has halted the natural progression of traditional—"Other"—societies.[2] Mosquera, through his claimed “Marco Polo Syndrome”, assesses Eurocentrism and how it affects the natural progression—or modernity—of “other” cultures outside of the West.[2] Olu Oguibe, on the same note, argues that Eurocentrism assumes that history—and thus modernity—is synonymous with the history of the West, labeling other cultures outside the West as “other”. [5] Within Eurocentrism, we run the risk of re-creating societies with a Western perspective, because of their own voices being silenced by the effects of colonization. Effects of colonialism has brought upon Eurocentrism, which is another form of hegemony that Western and European cultures have created to stifle their political foundations as well as socio-cultural. Many use art, an expression of culture, as one of the ways of coming to terms with where they stand within social and cultural relations. Members of the dominant group—of Western/European culture—habitually use art as a stratagem to exemplify their knowledge of the natural world, and to explain and validate their power over minority groups, a destructive result of colonization.

Effects on Visual Art

First Nation Art

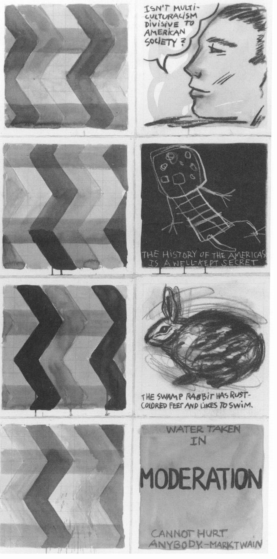

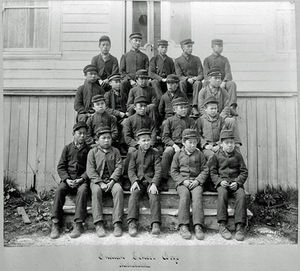

Often within cultures outside of the Western or European ones, there is a lack of participation in contemporary discourse in visual arts, which is an indirect cause of Eurocentrism. As Kay WalkingStick has accused, "critics often avoid writing seriously about Native American art because what they consider 'universal art values' are actually twentieth-century Eurocentric art values". [6] Without doubt, First Nation people have gone through the awful effects of colonization (ie. residential schools), and thus Eurocentrism, the results still apparent today. This notion of “other” cultures is used by Western artists and critiques not to describe the originality of the art or its roots, but to assert the West’s political and social dominance and sense of egotism due to their so-called “progressive and civilised” culture.

Within First Nation arts, it is worthwhile to mention the commodification and business of visual arts. One of many reasons why critical discourse of First Nation visual culture is seemingly dead is that many First Nation artists turn to art as a form of creating income, and therefore often paint to please a certain kind of taste—that taste unsuspectingly being a Western one. As WalkingStick has said, "painting strictly for the market leads to the loss of an indigenous pictorial viewpoint, or prevents the development of one". [6] She has accused that the kinds of paintings, and art work in general, that come out of mass-culture value are works that generalize and stereotype symbols which "white culture has identified as Indian...making indigenous people appear remote, generalized, savage, and...not real people". [6] In other words, it is a gratification of white culture, and thus a gratification of Eurocentric ideals.

Art history has, through many of its European epistemological technologies, reinforced what are in fact colonialist perspectives, judgments, and rationales. [7] An effect of Eurocentrism is the attempt at keeping "other" cultures in the past, somehow creating a contest between traditional and contemporary. An example of this could be the discussion of artwork being placed in museums for historical viewing rather that for art's own autonomy. The Museum of Anthropology at UBC, although harboring many contemporary art works of First Nation groups and people, can be assumed otherwise from merely the title of the institution. "Museum" is defined as a place where objects are exhibited [8], and "Anthropology" is defined as the study of human beings and their ancestors.[9] With both terms being rooted in the study of something in the past, it can seem as if the works shown in these institutions are something of the past—something that is a part of history and over with, when in actuality, it is attempting to be part of a contemporary discourse.

"We might reasonably recognize that notions about art and the discipline of art history are inextricably intertwined with European colonization...While much has been written about the development of anthropology in concert with Europe's colonizing agenda, those of us who practice art history in regions once colonized by Europe have questioned very little the ways our discipline enables certain avenues of investigation while discouraging others, about how the questions we ask and the things we choose to examine often respond to colonial discourses and are shaped by European disciplinary apparatuses."[7]—Carolyn Dean in The Trouble with (the Term) Art

Eurocentrism in Recent Years

The fact that this term actually exists is the acknowledgment of the dominance that European/Western culture has on not just First Nation culture, but others as well, which is the first step in the critique of art historical institutions and discussions. As Olu Oguibe has said, “for every One, the Other is the Heart of Darkness”[5], whether the West being the “One” or vice versa. What is important, however, is the addressing and the critiquing of this very concept of Eurocentrism, creating a truer sense of universality among different cultures that is not based and focused on a Eurocentric ideals, and creating art for art's sake and autonomy.

References

- ↑ Eurocentric. (n.d.). Retrieved November 16, 2016, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Eurocentric

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Mosquera, Gerardo. “The Marco Polo Syndrome: Some Problems around Art and Eurocentrism.” Theory in Contemporary Art since 1985. Ed. Zoya Kocur and Simon Leong. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2013. 314-18. Print.

- ↑ http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/residential-schools/

- ↑ "Inquiring Minds: Studying Decolonization." The Library of Congress Blog. July 29, 2013. Retrieved November 16, 2016, http://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2013/07/inquiring-minds-studying-decolonization/

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Oguibe, Olu. “In the ‘Heart of Darkness’." Theory in Contemporary Art since 1985. Ed. Zoya Kocur and Simon Leong. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2013. 324-27. Print.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 WalkingStick, Kay. “Native American Art in the Postmodern Era.” Art Journal, vol. 51, no. 3, 1992, pp. 15–17. www.jstor.org/stable/777343.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Dean, Carolyn. “The Trouble with (The Term) Art.” Art Journal, vol. 65, no. 2, 2006, pp. 24–32. www.jstor.org/stable/20068464.

- ↑ https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/museum

- ↑ https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/anthropology