Documentation:Open Case Studies/FRST522/Myanmar Community Forestry the status, challenges, and recommendations

Myanmar Community Forestry: the status, challenges, and recommendations

This video shows Myanmar local people's dependence on forest products, and gives reader an brief view about what can Community forestry bring to local dwellers.

Executive Summary

Started in 1995, Myanmar's Community Forestry is gradually seeing positive progresses while learning from past experience and lessons. Due to various climate conditions, as well as economic and social factors across Myanmar, almost 600 Forest User Groups are having different experience about Community Forestry. Generally, Community Forestry benefits Forest User Groups with improved forest resources quality, better livelihood support, increased income, restored biodiversity, and less outside interference. However, a certain portion of Forest User Groups are not functioning well, or even suffering stagnation. The reasons include: insufficient support from Forest Department, elite capture, lack of post-formation support, low participation rate of community forestry, low Community Forestry-related knowledge awareness, and inequitable profit shares. It is recommended that the government strengthen the training of the staff, and the support provided to Community Forestry. The communities should keep improving the management model, and reform the management system according to different needs. Ensuring that the marginalised groups can also participate in decision making process is very crucial to form the positive cycle, and improve Myanmar Community Forestry from fundamental level.

Description

Myanmar occupies 67.6 Million hectares of land area. 48% of Myanmar is covered with forest. This country is suffering from constant forest loss. [2] Figure 1 is a map of Myanmar.

The forest loss is mainly caused by factors below: Forest area changes to other land areas due to growing population; Excessive timber harvesting; Excessive livelihood need - driven forest product harvest (including fuelwood, leaf harvesting), etc [2]. Community forestry (CF), proven to be a successful forest management form around the world, has also been implemented in Myanmar. The majority of the projects was started and promoted by Myanmar Forest Department (FD), and international donating organisations like UNDP, DFID, and JICA [2].

This Wiki page will provide readers with a general introduction of CF in Myanmar. In Myanmar, CF was first lunched in 1995 [3]. The latest Community Forestry Instruction (CFI) was published in 2016 by The Republic of the Union of Myanmar, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation, Union Minister Office. The Instruction wrote that “Community Forestry means all kind of forestry operations for sustainable forest management in which local people are involved.” [4] Location of CF are mostly in Shan, Mandalay, Magway and Ayeyarwady [3]. The Forest User Groups (FUG, see section “Affected Stakeholders”) are the main participants. They are allowed to form Community Forest Enterprises (CFE) to better fulfill the CF management Goals.

The objectives of Myanmar CF are [4]:

1. Fulfilling the need for Forest Product and Non-timber Forest Product of Forest Dependent group

2. Reducing Poverty by creating more job opportunities and income

3. Managing forest to realize sustainable forest resource supplies

4. Increasing participation motivation and rates of local people during forest management processes

5. Conserving ecosystem services, mitigating climate change, reducing deforestation and forest degradation

Tenure arrangements

All lands in Myanmar are owned by the state [3]. The forest lands are under the management of Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry (MOECAF). Other land types are under the management of Department of Settlement and Land Records under the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation[2].

Once the CF is approved, the CF tenure is granted for 30 years. At the end of the 30th year, if the outcome of CF is desirable, the District Forest Officer (DFO) can granted for another 30 years according to FUG’s wills [4].

Under the advice of Forest Department (FD), FUG will draft and submit a Management Plan (MP) to DFO. After the MP is approved, DFO will release CF certificate (Please see section “Administrative Arrangements”)[4]. From then on, FUG should act and manage the CF area according to the MP, otherwise DFO has the rights to revoke the CF certificate[4].

FUGs are prohibited to[4]:

1. Conduct other activities that is not written on the MP on permitted CF land

2. “Selling, borrowing, lending, transferring, and donation of CF”, according to CFI.

3. Extract other resources such as sand, stone, minerals.

4. Construct, or live in permanent buildings that is not related to CF implementation.

5. Plant anything that is not allowed by the national law of Myanmar.

FUGs have certain rights which will be discussed in later sections.

Administrative arrangements

According to Myanmar CFI, to start the Community Forestry, Forms need to be filled and CF certificate should be obtained from Forest Department (FD) under MOECAF[4]. The steps can be concluded as follows [4]:

1. FUGs are formed with people and groups which are interested in CF, and directly depend on forests

2. Facilitators (FD and NGOs) provide advice, and financial aids if needed.

3. Management Committee (MC) of a CF group is formed

4. The Chairman of MC will submit Forms to apply for CF from Township Forest Officer towards DFO.

5. DFO starts the assessment process.

1) If the Proposed CF area is under FD’s land management area, the DFO will have the power to approve CF applications, and submit the complete file to Direct General (DG) of FD.

2) If the Proposed CF area is under the Buffer Zone, the DFO must transfer the decision-making rights to DG of FD.

3) If the Proposed CF area is not under FD’s land management area, the DFO will transfer the decision-making power to relevant other organizations, or government agencies.

6. Once CF is approved, the DFO has the rights to define the allocation of the land based on applicant's number of households, natural environment, objective of CF, and other factors . The Forest User Group (FUG) in CF has the rights to ask DFO for advice.

7. Once CF is approved, the FUG need to form up management plans (MP). MP must be approved by DFO. Revision of MP should be done with the advice of FD, and approved by DFO.

8. Once MP is approved, CF certificate will be released by DFO. A CF region is thus formulated.

According to Myanmar CFI, the fund in an FUG is allocated according to following rules [4]:

1. Fund must be kept in a bank account

2. MC chairman, secretary and treasurer can gain access to this bank account

3. MC Treasurer is responsible to maintain expenditures, earnings, and other factors related to the bank account, and report to MC and FUG

4. The benefit sharing about the fund must be in accordance with MP

5. When being allocated, the fund can be individual income, village development, afforestation of CF, etc. according to FUG's need

Affected Stakeholders

The affected stakeholders here is FUG. According to Myanmar CFI, FUG are people/households living 5 miles around the forest area[4]. They need to be stay there for 5 years, and depend their lives on forest resources. Also, they will unite with interested stake holders (see section “Interested Stakeholders”) to implement CF management items. [4].

Myanmar FUGs have rights as follows [4]:

1. Succession of the rights from person who are endowed with CF rights

2. Changing FUG members (This is the right of MC)

3. Changing MC members with the consent of the majority of FUG members

4. Getting rid of land rental charge

5. Accepting assistance from interested stakeholders

6. Conducting appropriate Agro-forestry practices

7. Extracting and utilising Forest Products from CF areas

8. Registering CF based enterprises

9. As legal entities, commercialising, selling, and marking Timber products from CF areas

10. Claim for loss if CF area is interfered by other development projects

11. Under the permission of FD, extract the forest products included in the MP. FD's permission is not necessary, and FD should exempt the tax on these forest product if Forest Product extracted is for self - use

12 Register CF Based Enterprises, and form Association between FUGs in order to better perform the business activities

13. Transport and sell CF products with reasonable prices inside the village without paying tax, and outside the village with tax amount paid

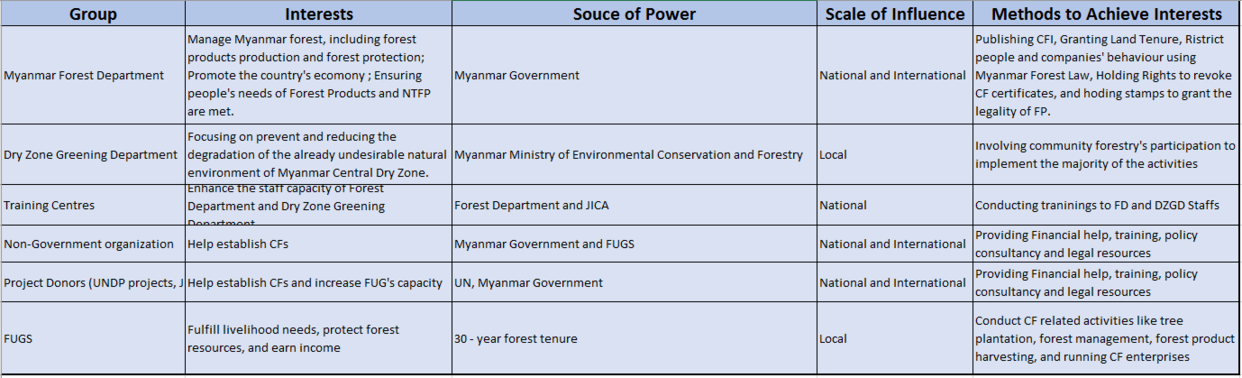

Interested Outside Stakeholders

According to Myanmar CFI, “Facilitators are Forest Department staff and INGO/NGO organizations who assist and advice to local people in CF application, FUG formation, Management Plan formulation, and CF implementation activities and process.” [4] These people are getting paid with salaries, they do not depend on forest to live. Therefore, they are Interested Outside Stakeholders. Private enterprises and organisations, national and international institutions, as well as Myanmar FD, are all interested stakeholders.

Myanmar Forest Department

Myanmar Forest Department is a department under MOECAF. It was established 140 years ago. This department comprehensively manage the planting and extraction of timber, fuelwood, bamboo and other forest products. CF is under Myanmar FD's management. [5] FD has the actual authority to issue legal tenure to community forests. The other department under MOECAF, including Dry Zone Greening Department (DZGD), Myanmar Timber Enterprise (MTE), and Planning and Statistics Division, do not have such rights. [6]

Myanmar FD has rights as follows: [4]

1. Issue forest laws and rules that CF needs to follow

2. Decide which type of tree and crop is allowed to be planted in CF zones

2. Acknowledge what type of assistance does FUG take from other organisations

3. Revoke CF Certificate if CF management outcome is severely not in accordance with MP, or when FUG violates forest laws and rules issued by FD

4. Collect Tax from CF income involving exterior townships

5. Acknowledge changes in MC and FUG members

6. Collect report from FUG

Project Donor organisation

Project Donor organisations are either national or international organisations which help build up CF via providing multiple forms of supports. One example is UNDP (United Nation Development Program) provide Myanmar with Local Governance Program. The objective of this 3-year program is: Enhancing the capacity of local residences, including FUGs. By providing financial aid, employment services, career training, rural entrepreneurship support, and improving media capacity, this program can help the FUGs to conduct CF management more effectively. The rights UNDP has in this project include: Collecting data to assess local governance; Cooperating with reginal government members to set up and implement training programs; Introducing organizational measures; Institutionalization the capacity civil society organization according to the needs of capacity building processes; etc. [7] Other project donors like japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), Pyoe pin, and Forest Resource Environment Development and Conservation Association (FREDA) are also providing multiple support for Myanmar CF build-up and capacity enhancements. [8]

Illegal Loggers

Illegal loggers will get in the territories of CF regions and log valuable wood. Illegal loggers is taking the resources away from FUGs.

Discussion

Overall Community Forestry Progress in Myanmar

The original FD Master Plan is to establish 2.27 million acres of CF regions within 30 years, started from 1995. Until 2011, the progress of CF establishment and handover was still way beyond the progress [9]. On average, only about 7000 acres of land was handed over, while actually 50,000 acres of land should be established as CF if the FD's Master Plan was to be completed. Implementation of CF were mostly promoted by international donor projects like JICA and UNDP. Shan, Rakhine, Magway and Mandala enjoys the highest implementation rate. Therefore, the annual handover rate must be increased. The main reason that caused the delays are: CF handover works were not prioritised; Insufficient commitment and motivation of FD staff; Slow CF application approving process; Rural communities' reluctance to accept CF policies and tenure, etc. [9]

Overall Performance, according to goals

Setting the CF establishment progress aside, the overall performance of existing Myanmar CF can be regarded as medium - good. [10] According to a study done in 2011 using sampling survey method, half of the FUGs are well institutionalised, while 31% and 19% were performing moderately and poorly respectively. Only 19% of the FUGs were protecting the forest with good results. 50% saw an moderate result, while 12% of the FUGs failed to protect the forest within CF regions. Half of the FUGs saw improved forest condition after the implementation of CF policies, 31% got moderate results, with 19% did not get forest condition to anywhere better. Half of the FUGs experienced equity within CF management area, while 12% FUGs' benefit was inequitably distributed. The best news is, the majority (81%) of FUGs got improved benefits due to CF implementation. The rest (19%) feels the benefit brought by CF was moderately well. [10] Geographically, the weak - CF performance generally concentrates in Mandalay and Shan State. Well performed FUGs have attributes as below, which is in accordance with some of the Ostrom's 8 design principle for Common Property [11]: Clearly defined user and resource boundaries, and high awareness of rules; Rules in MPs match local conditions; High participation rates; etc. The FUGs which are poorly working or stagnate completely often suffer insufficient understanding of FD's CF policies, little power around illegal cutting and grazing, incapable leadership, inequitable benefit sharing caused by 'elite capture', and shortage of support in different aspects. [10] The majority of the communities are experiencing moderate benefits brought by CF management. Their status is at somewhere in the middle of the two stages stated above. These FUGs can fullfill most of the required CF operations in MP, but also facing challenges such as insufficient support after establishment, FD's approval delay, illicit Forest Product gathering, leadership changes, etc. [10]

Overall Pre - CF situation

The majority of the CF area was to some extent deforested before CF certificate was approved. Due to lack of power to discipline outside illicit harvesters, and strong need to fulfill villager's own livelihood needs, over harvesting is common in villages. Among the 16 investigated village samples in the study, 81% suffers degraded forest, or deforestation problems before CF region was formed. [12]

Overall CF Forest Condition

Generally, Community forests are being protected well, or moderately well, with only 18% FUGs failed to efficiently protect their forests [13]. FUGs saw improved water supply qualities, increased biodiversity, less erosion, and better forest carbon sequestration abilities [13]. In CF management areas, there are planted forest, natural forest, or both. The survival rate of planted forest are generally above 75%, except the CF areas in dry zone (Mandalay) where the planting stock's survival rate is generally lower than 50%[13]. Due to the satisfying ground cover, erosion rate was reduced in CF areas. Although half of the investigated CF plants was attacked by diseases and pests, the forest health was satisfying. [13]

More than 60% of FUGs saw illegal extraction in their CF regimes committed by outsiders, or non-FUG members. Firewood, lumber, and other NTFP are targets of illegal extracting activities. [13]

Institutionalisation

According to the study conducted by Kyaw Tint et al., 50% of the studied FUGs are well institutionalised [14]. 19% of the FUG sample failed because of the elite capture problem [14]. The majority of the CFs were formed under the help of donor's support, with a small portion that were self-started, or established under the help of local NGOs. Villagers have basic concept of protecting the forest and their territory, and 93% of the investigated FUGs were motivated to manage their Forest area properly. However a certain part of them are unclear of the actual content of CF management plan, or the rules announced by FD.For example, When doing selections, people blankly vote without knowing the selection categories. Even worse, some villagers are being excluded out of the decision making events [14].

Although FD require FUGs to get CF certificate before establishing CF regimes, some FUG established CF 1-3 years before the approval of CF certificates due to delays in receiving CF from FD. [14]

Income

CF helped FUGs to realise positive income flows. Since forest are planted, or regenerated, the forest product supply is getting more and more sufficient to fulfill villager's needs of fuel wood, poles, food to feed themselves and their livestock. [15]The income coming from selling products from forest plantation, like thame plantation, is very high. The Internal Rate of Returm (IRR) of this plantation within 10 years is 24.28% ref name="Kyawincomes"/>. After 6 years of initial plantation, planters can see a positive net cash flow[15]. Under government's allowance of the establishment of CF enterprises. CF enterprises is using market-led approach. (namely “1. securing commercial tenure 2. improving technical know-how; 3. building business skills and 4. strengthening producer organisation.”) [16]. This approach is getting more and more support from not only Myanmar government, but also the civil societies. With this approach, local people can hold the value of the resource tight in their hand, and generate stable income. [16]

Equity

According the study carried out by Kyaw et al., 37.5% of the studied FUGs are being equitable when managing the community forestry lands [17]. When sharing the benefits, these FUGs pay special attention to poorer households, and even non-members [17]. 50% of the studied FUGs are doing moderately well, with issues such as: lacking consideration on poorer house holds, having outsiders taking benefits, having small group sharing benefits across the village, and having only a certain type of products shared equally and leaving the rest benefits shared unequally, etc[17]. Across Myanmar, poorer house holds tends to be more vulnerable to meet inequitable treatments in CF regions. They are engaged in daily works to supply their basic living needs, which squeeze their time to participate in CF management activities [17]. However, they are the group who depend more on forest products from CF lands. This constitutes a positive cycle when they are in an FUG group that is not equally share benefits to poorer participants. [17]

Assessment

Recommendations

FD should provide FUGs with sufficient support: CF certificate approval speed and progress is sometimes slow, which needs to speed up via streamlining the policies of CF formation; when outsiders get into the villages and were reported by FUGs, FD should provide in-time back ups to evict illicit harvesting and extracting activities [18]. If the problems are due to lack of capabilities of FD staff, training should be provided to staff, and dysfunctional groups is in need of a reform. Also, if the provision of post formation support to FUGs is poor, FD should provide necessary support until FUGs can function well on their own. The Support FD can provide includes: Strengthening FUGs' awareness of CF management rules and CF Instructions; Provide consultation and necessary work force to aid the conflict resolution and monitoring process within CFs; Provide financial and aids to marginalized CF groups; Provide strong legal support when to illicit invading groups reported by FUGS. [18]

There are certainly portion of FUG groups remain stagnated. Therefore, a system should be created to monitor the stagnated FUGs nationwide, in order to find out which FUGs are in stagnating status, and what was the reason behind the stagnation. [18]

When meeting difficulties, FUGs should diversify their sources of support. When FD's support and resources are insufficient, FUGs can turn to international NGOs, or other donor projects. They can even take initiatives to seek support by themselves. Regards to benefit sharing, the marginalised groups (such as the poorer households) should be taken special care of. They should be educated with the actual content of FUGs, and be granted with the allowance to access the resources. When they are able to get their share of returns from CF, they tend to be more motivated to participate in CF related activities. A positive cycle can thus be established. For the "elite capture" problem that exists in some FUGs, villagers could form groups and make sure that the management committee of CF do not only includes a certain groups of elites. Instead, all villagers within CF region should participate in the management and selection process. [18]

References

- ↑ RECOFTC (2011). Voices of the forest: Myanmar. [image] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bddjA0saQ_M ,

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Kyaw Tint, Springate-Baginski and Mehm Ko Ko Gyi. (2011). Community Forestry in Myanmar: Progress & Potentials. Myanmar: Ecosystem Conservation and Community Development Initiative, School of International Development, University of East Anglia. Retrieved from http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs13/Community+Forestry+in+Myanmar-op75-red.pdf ,

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Lin, H. (2005). Community forestry initiatives in Myanmar: An analysis from a social perspective. International Forestry Review, 7(1), 27-36. doi:10.1505/ifor.7.1.27.64154 ,

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 Ohn Win. (2016). Community Forestry Instructions (pp. 2-3). Naypyitaw: The Republic of the Union of Myanmar, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation. Retrieved from http://share4dev.info/kb/output_view.asp?outputID=5360 ,

- ↑ Wikipedia (2017). Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry (Myanmar). [online] En.wikipedia.org. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ministry_of_Environmental_Conservation_and_Forestry_(Myanmar) ,

- ↑ Hlaing, E. E., Swe, & Inoue, M. (2013). Factors affecting participation of user group members: Comparative studies on two types of community forestry in the dry zone, myanmar. Journal of Forest Research, 18(1), 60-72. doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/10.1007/s10310-011-0328-8 ,

- ↑ UNDP. (2015). Local Governance Program summary. UNDP in Myanmar. Retrieved 7 November 2017, from http://www.mm.undp.org/content/myanmar/en/home/operations/projects/poverty_reduction/LocalGovernancePillar1/ ,

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Kyaw Tint, Springate-Baginski and Mehm Ko Ko Gyi. (2011). Community Forestry in Myanmar: Progress & Potentials. (pp. 22). Myanmar: Ecosystem Conservation and Community Development Initiative, School of International Development, University of East Anglia. Retrieved from http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs13/Community+Forestry+in+Myanmar-op75-red.pdf ,

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Kyaw Tint, Springate-Baginski and Mehm Ko Ko Gyi. (2011). Community Forestry in Myanmar: Progress & Potentials (pp. vii, 27). Myanmar: Ecosystem Conservation and Community Development Initiative, School of International Development, University of East Anglia. Retrieved from http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs13/Community+Forestry+in+Myanmar-op75-red.pdf ,

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Kyaw Tint, Springate-Baginski and Mehm Ko Ko Gyi. (2011). Community Forestry in Myanmar: Progress & Potentials (pp. 69-71). Myanmar: Ecosystem Conservation and Community Development Initiative, School of International Development, University of East Anglia. Retrieved from http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs13/Community+Forestry+in+Myanmar-op75-red.pdf ,

- ↑ Ostrom, E., & Cambridge Books. (2015). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action (Canto Classics ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press.,

- ↑ Kyaw Tint, Springate-Baginski and Mehm Ko Ko Gyi. (2011). Community Forestry in Myanmar: Progress & Potentials (pp. 30). Myanmar: Ecosystem Conservation and Community Development Initiative, School of International Development, University of East Anglia. Retrieved from http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs13/Community+Forestry+in+Myanmar-op75-red.pdf ,

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Kyaw Tint, Springate-Baginski and Mehm Ko Ko Gyi. (2011). Community Forestry in Myanmar: Progress & Potentials (pp. Viii, 42-46). Myanmar: Ecosystem Conservation and Community Development Initiative, School of International Development, University of East Anglia. Retrieved from http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs13/Community+Forestry+in+Myanmar-op75-red.pdf ,

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Kyaw Tint, Springate-Baginski and Mehm Ko Ko Gyi. (2011). Community Forestry in Myanmar: Progress & Potentials (pp. viii, 33). Myanmar: Ecosystem Conservation and Community Development Initiative, School of International Development, University of East Anglia. Retrieved from http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs13/Community+Forestry+in+Myanmar-op75-red.pdf ,

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Kyaw Tint, Springate-Baginski and Mehm Ko Ko Gyi. (2011). Community Forestry in Myanmar: Progress & Potentials (pp. ix, 52). Myanmar: Ecosystem Conservation and Community Development Initiative, School of International Development, University of East Anglia. Retrieved from http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs13/Community+Forestry+in+Myanmar-op75-red.pdf ,

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Macqueen, D. (2015). Community forest business in Myanmar: Pathway to peace and prosperity?. Research Gate. Retrieved 4 November 2017, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/299393306_Community_forest_business_in_Myanmar_Pathway_to_peace_and_prosperity ,

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Kyaw Tint, Springate-Baginski and Mehm Ko Ko Gyi. (2011). Community Forestry in Myanmar: Progress & Potentials (pp. viii, 59). Myanmar: Ecosystem Conservation and Community Development Initiative, School of International Development, University of East Anglia. Retrieved from http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs13/Community+Forestry+in+Myanmar-op75-red.pdf ,

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Kyaw Tint, Springate-Baginski and Mehm Ko Ko Gyi. (2011). Community Forestry in Myanmar: Progress & Potentials (pp. 70-71). Myanmar: Ecosystem Conservation and Community Development Initiative, School of International Development, University of East Anglia. Retrieved from http://www.burmalibrary.org/docs13/Community+Forestry+in+Myanmar-op75-red.pdf ,

| This conservation resource was created by Course:FRST522. |