Documentation:Open Case Studies/FRST522/Ekuri Forest community of Cross Rivers State, Nigeria and the price of development

Ekuri Forest community of Cross Rivers State, Nigeria and the price of development

Ekuri Forest Community is the most prominent example of community forest outlook in Nigeria. They are a minority tribe in Nigeria. They have continuously lived in the Ekuri Forest for thousands of years and the forest serves not just as a home for them but also a source of their livelihood. The exemplary outlook of the well managed Ekuri forest by the locals brought a lot of attention in terms of interested stakeholders such as the government, local and international NGOs. Each of these stakeholders has their relative scale of influence and sources of power and through their involvement, the Ekuri Forest community metamorphosed into a modern and broadly managed initiative. However, in 2016, the Cross River State government proposed to construct a 6-lane highway that will cover the entire 3,600 hectares that accommodates the Ekuri people. This has been a huge problem for the Ekuri people as there is the high chances of losing their ancestral home and the only source of livelihood they have. However, despite the many global and local calls for a necessary rerouting of the proposed highway, the State government is still bent on carrying on with the plan. Unfortunately, Nigeria is not a signatory to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, this limits the part of Free, Prior and Informed Consent. However, to prove a case for the Ekuri people, this piece of work reflects on the provision of the Nigerian Environmental Impact assessment and some international conventions that Nigeria is a signatory to.

Description

Introduction

Cross River State, is located in the Southern part of Nigeria. It is a coastal state and it has an actual size of 20,156km2. It shares borders with Benue State, Abia State, and Ebonyi State and its the home of the great Cross River rainforest. The Cross River rainforest remains a very important part in Nigeria as it plays an all-important role in being the remnant of the entire rainforest belt of Nigeria. The forest size is around 8,506 square kilometers which is approximately 2.4% of the total land surface of Nigeria. The Cross Rivers forest is characteristically a low land forest commonly found in the southern part of Nigeria with a year-round rainfall pattern. This low land forest of Nigeria is a rich hub of biodiversity and contains a lot of tree species with economic potentials, which has subjected the forest to a great deal of unhealthy exploitation. [1] Due to the continuous presence of indigenous people in this forest areas, there has been an age long dependence on the forest for livelihood and this has overtime influenced the system of community ownership of forests within Cross Rivers state forests. A total of 29.5% of the forest area has been noted to be under the direct management of the local communities living within the forests. However, there also exists a land reservation for the national park and the forest reserve within the same vicinity of the community-managed forest, with both reserved areas occupying a land area of 3,330 square kilometers and 1,810 square kilometers respectively.)[2] The Nigerian forest estates, however, are all under the control of the state governments, so the introduction of community-based forest management in Nigeria is still in the building process as there are just a few records of such in the country. However, within the context of including community forest management practice into national policies, Nigeria is making efforts to join the rest of the world in recognizing the necessity of the social content inclusion into the various processes of conservation. A few indigenous communities have registered as corporate initiatives under the government, and one of such and the most recognized nationally and globally is the Ekuri Forest Initiative. (Ogar, 1990)[3] Since the state government of each state in Nigeria has the authority and control over their forest, Cross Rivers State, which is the home state of the Ekuri community has in its provision a rule of law that recognizes community forests as protected areas or communal land for the use of communities. This gives the right of use to communities or locals that have been recognized by native laws as owners or natives of a particular area of land and the natural resources therein.

About Ekuri Community

For thousands of years, people have continuously lived in the lowland forest region of the Cross River rainforest and are dependent on the forest for their sustenance and livelihood. The forest is often exploited for its abundant timber and non-timber resources. Right there in the forest are a number of forest-dependent communities among which is Ekuri Forest community. Ekuri forest area covers a total area of 33,600 ha and its location is near the Cross River National Park. The Ekuri ethnic group is known as the Nkukole people and the local language is lokori. The Primary occupations of most people in the community are farming, trading in non-timber forest products, hunting and fishing. Ekuri is however subdivided into two communities namely, the new Ekuri and old Ekuri and they are just some 7 km apart and with a population of 6,000 people.[4]

Tenure arrangements

Ekuri Community Leadership

According to age long customary laws, which differs in content from one local region to the other, the village head or chief has the power to make decisions with the support of local chiefs who are often representatives of different groups within the community and there is also the class of family representative as each family is entitled to an estate of land. The right of ownership by the people is always recognized by inheritance laws and local history. [5]

Rights and Ownership

However, the description by National law does not make provision for the status of complete ownership of the forest land and that means that the communities in charge must still answer to a higher authority which is the government. However, there is an allowance for benefit sharing. A Certain percentage (70% to communities and 30% to the coffers of the government) from Proceeds obtained from various aspects of forest utilization goes into the coffers of the government and while the government lends technical support to the community. .[6] .[7] The Landuse Act of 1978 which puts the lands in Nigeria under the control of the government and this has limited the right of ownership of the locals. The extent of power that the state has over the Forest has not allowed the locals have a free hand to control their forest and this has often resulted in conflicts. The situation is well modelled in the proposed highway that the State government is currently planning to construct through the forest of the Ekuri people. Even though the Ekuri people have been known to have a level of claim of ownership on the forest in question, the State government, in a bid to use its veto power, still went ahead without proper consultation to embark on the much talked about superhighway.[6] [1]

Forest Resource Management

The forest is managed as a common property which nobody owns in the actual sense. Exploitation of the forest is carried out within a stipulated customary rule and guidelines which must not be broken. There is also the practice of collective harvesting of non-timber forest products such as edible leaves, snails and bush mangoes. This is done in accordance with schedules framed for each of the non-timber products harvested and the specified period that harvesting can be carried out. Every participant in the collection and sales of these products would have to register under the community registry which would warrant the payment of a compulsory due. No one can be allowed to take part in the harvesting business unless they are registered. This is one way the community has been generating fund and another way is the collection of taxes and gate fees from outsiders who come on a regular basis to take purchase and take part in the harvesting business. With this reserve base of fund, the community has set up a microcredit scheme that has been utilized to develop the community and to provide support in terms of scholarships and loans.[8] [1] In Ekuri, everyone has open access use of trees although not on a commercial level. The trees are communally owned and that means for communal harvesting, but commercial harvesting can only be done together through the Ekuri initiative. Certain plots of land set aside for trees can be ventured into for harvesting using a guiding principle. However, other communities or individuals do not have a direct right to use the forest except they have the permission to do so under the monitoring of the community chiefs. The Ekuri community has been working on certain principles which serve as the template for regulating the rate of harvesting and provides a means of earning revenue.[1] Just like the case of Naidu village as discussed in the Menzies’ book titled “Our Forest, Your ecosystem, Their timber”. The Naidu villagers have a set of guidelines with regards to the harvesting of the highly prized but fragile matsutake. This is about the same approach of the Ekuri people as to the harvesting of the edible forest leaves which is highly prized as well. The approaches relate to a regulated period of harvesting, allowable harvest per time and the control on entry into the forest by even the villagers and outsiders. Another observed similarity is the collective approach adopted by both initiatives and the inclusion of interested stakeholders like the case of International NGOs.[9]

Administrative arrangements

The management of the forest under the Ekuri community started in the year 1980, borne out of the need to collectively protect the value of their forest. Also, worthy of note is the fact that Ekuri is divided into two, the new Ekuri and the old Ekuri, with a long existing history of conflicts of interest which has limited development in both areas, but then, a situation aligned their interests. [8] So, it happened that the local communities of Ekuri have had great difficulty in reaching the outside world to access city markets for commodities that might not be easily obtained in their communities. This discomfort triggered the need for development. They eventually approached a logging company to negotiate a deal regarding logging rights for the construction of a road that will directly connect the communities to the township. However, the logging company wanted more than enough and coupled with the fact that the communities placed a high value on their forest right from time, they declined the offer. They resorted to imposing certain community levies upon themselves and through this, the communities were able to raise enough money just to construct a 40km road between old Ekuri and the new Ekuri. The success of the united stand of the communities (the old and new Ekuri) for the protection of the major source of their livelihood from unhealthy logging led to the beginning of the formal recognition of the Ekuri community forest management. This led to the establishment of a cooperative society that monitored and regulated harvests from their forests. With time, the local initiative caught the attention of the State Government and this influenced the Cross Rivers State National Park to assist the existing scheme because Ekuri is one of the old villages mapped out under the support scheme of the external sponsors of the national park.[8] The government provided the community with the permission for the management of their forest. This afforded the community the right to their forest and its resources. Also, the government ensured their presence as they stationed a forest officer to protect their interest and to provide technical support in the management of the forest by the communities. Hence, Ekuri Forest community became the first recognized Joint forest management program in Nigeria. The introduction of Joint forest management brought along many partners and benefits such as the influence of the Forest department and the establishment of Ekuri initiative in 1992. The Ekuri Initiative was established for the purpose community development and for the specific objectives of reducing poverty, supporting education by providing scholarships and the development of a credit and loan scheme. [8] The program has been highly participatory with the involvement of the locals in major processes entailed in management such as inventory and land use planning. In so many ways, the communities have been able to adopt certain principles of land use approach and this has reflected in the content of capacity building, leadership strengthening, and local participation. The Ekuri forest in partnership with some multinational agencies and local organizations successfully demarcated the community forest into 5 different zones. The agroforestry zone, non-timber forest zone, protected area and animal corridor, farming and cash crop zones and ecotourism zones.[8]

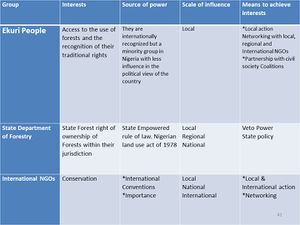

Affected Stakeholders

The community initiative is an inclusive one that involves the whole community being represented by the different social and trade groups such as the women association, the snail sellers’ association, herbs sellers’ association and the youth group. However, decision making power is vested in the community leadership forum which is made up of chiefs representing the different social and trade groups.

Interested Outside Stakeholders

Due to the fact that Cross River is a hotspot zone because of it being the home of many endangered species like the drills, a number of international agencies have risen to provide support for the protection of the area and that includes the recognized villages within the proximity of the national park. The extension of the international support for the local villages in close proximity of the national park is to ensure less interference with the conservation effort. Ekuri Village happens to be one of the recognized villages. The involvement of many international partners brought a great deal of sophistication that helped to improve the management of the Ekuri Forest. The major partners with the State government helped to provide the necessary capacity building skills for the locals to enable them to understand the technicalities involved in forest management. The Partners of the Ekuri Forest Initiative up to date are as follow: Cross River National park, Cross River state forestry commission, Ford Foundation, Forest management foundation, Bonny allied industries, Crushed Rock Industries, Global green grant, IUCN, European Union Micro Projects Programme, UNDP/GEF Small grants program.[8]

Discussion

The management of the forest under the Ekuri community started in the year 1980, borne out of the need to collectively protect the value of their forest. The success of the united stand of the communities (the old and new Ekuri) for the protection of the major source of their livelihood from unhealthy logging led to the beginning of the formal recognition of the Ekuri community forest management. This led to the establishment of a cooperative society that monitored and regulated harvests from their forests.

Conflict of Interest

The Landuse Act of 1978 which puts the lands in Nigeria under the control of the government and this has limited the right of ownership of the locals. The extent of power that the state has over the Forest has not allowed the locals to have a free hand to control their forest and this has often resulted in conflicts. The situation is well modelled in the proposed highway that the State government is currently planning to construct through the forest of the Ekuri people. Even though the Ekuri people have been known to have a level of claim of ownership on the forest in question, the State government, in a bid to use its veto power, still went ahead without proper consultation to embark on the much talked about superhighway. [1][6]

Highway Construction

In 2016, the Cross River State Government announced a highway construction proposal which is expected to boost the economic prospects of the State. However, it is rather unfortunate to learn that the proposed highway will cut right through a large portion of the pristine rainforest that has earned the State a position of esteem globally. Most importantly, the whole of the Ekuri community would have to give way to complete demolition for the proposed development. This has brought a lot of agitation both locally and Internationally. Local NGOs and international organizations have continuously engaged the State Government in dialogues, protests and open calls with the possibility of shelving the idea or rerouting the highway to save a larger proportion of the remnant of the rainforest of Nigeria and at the same time the Ekuri Forest community that the whole world has come to recognize. The consultation has reached the office of the national Government and this led to the call for an Environmental Impact Assessment(EIA). Although the State Government produced a documented EIA report, this has been turned down and unaccepted by the stakeholders and even the federal government on the grounds of observed errors and omissions. The proposition of the construction of the highway was not done with prior consultation with the Ekuri people and this violates the ethics of community development with regards to the elements that will be impacted. Additionally, the Nigerian Environmental Impact Assessment Act( Part 1, section 1(a) “to establish before a decision taken by any person, authority corporate body or unincorporated body including the Government of the Federation, State or Local Government intending to undertake or authorise the undertaking of any activity that may likely or to a significant extent affect the environment or have environmental effects on those activities shall first be taken into account.[10] this implies that prior to any form of physical construction through a forest, a detailed environmental impact assessment must be carried out. Alas, this was not the case in Cross River state as the EIA report that was eventually prepared did not speak in clear terms and also because the government gave a go-ahead way before the production of the EIA, which speaks volumes about the irregularities and lack of transparency, as this is a violation on the part of the government.[11]

Impact of the highway construction

The highway is proposed to divide the forest into two and this means it will cut right through the protected forest and totally wipe out the Ekuri Forest community. The direct impacts of this include the extinction of the Ekuri community, forest degradation, and loss of ecosystem value of the forest which in consequence go back to hurt the state as the damage would reduce the potential of claiming REDD credit. [12] The highway is going to cover the entire 3, 600 hectares that accommodate the Ekuri forest community. This has been categorized as a typical land grab by the government. It is a complete alienation of the people from their ancestral ground and an outright violation of their basic human rights. Although, the governor is said to have rescinded his earlier orders on total land rights claim and the idea of a 20km corridor roads. However, it is not clear if these are just political tactics to silence opposition and global outcry. .[13]

The Failure of the Government

The State Government has failed to produce a detailed environmental Impact assessment report on the proposed highway construction. The reports provided have all been labelled fraudulent as a lot of inadequacies were noticed. However, a provisional approval was granted for the execution of the highway project on the 29th of July 2017 by the Federal Government of Nigeria, with a number of stipulated conditions which were to be met before the commencement of the construction. The stipulated conditions are listed below:

- “The State Government must provide compensation to the affected communities and persons that will be displaced in the process of the highway construction”.

- “The State Government has been mandated to provide a detailed plan that will show a rerouted road that will be at some considerable distance away from the National park and the Ekuri Forest community. Also included is the mandatory withdrawal of the 10-km space into the buffer zone of the National Park”.[14]

However, the situation has taken a different turn as the State Government has notified the Federal Government that the project would be carried out even without meeting the stipulated demands of the Federal government.

Assessment

The Ekuri people as the situation stands have no tangible grasp of power and they have only resolved to protests and open call with assistance from the global community. Whereas, the Government, on the other hand, has the veto power and has been exercising it by shoving its plans down the throat of the Ekuri people.

Recommendations

Ekuri Forest community represents the only prominent example of community forest practice in Nigeria and there has been a good record of success overtime. The template of practice has been such that other State governments had to adapt to serve as prototypes for other potential community forest initiatives. However, as it stands today, the price for development might rob the nation of a well and sustainably managed system that has come to be respected worldwide and a great example of what community forest should look like. At this stage, there is the need to tailor development in such a way that the rights of the people are protected and at the same time the integrity of the forests are not jeopardized.

Local

- The intervention of the federal government is highly imperative at this stage to protect the interest of the Ekuri forest community, and that can only be possible if the state government is forced to follow due process in finding alternative routes for the proposed highway. The report of the EIA must be followed to letter.

- As it stands the right of the Ekuri people to continue to own control over their forest is being threatened and they are so powerless to protect even their own interest, therefore support from the international community is needed.

- Free, Prior and Informed Consent is quite important for the indigenous people to have a say with respect to coming to terms with the impact of development. The Free, prior and Informed consent provides the indigenous people the right to make a choice concerning how development should proceed.

However, in the case of the Ekuri people, there are limited options for the recognition of their rights with respect to free, prior and informed consent. The provisions in the Nigerian constitution have largely conflicted with most international conventions that have to do indigenous peoples right. The reason being that every tribe represented in the country is indigenous and the country has been declared a sovereign democratic state upon independence.

International

The status of the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (International Labour Organization C169 (1989) that gives indigenous peoples the right to be part of any decision making has been challenged to be clearly in conflict with the provision of the Nigerian constitution. So, Nigeria is yet to ratify the convention. According to.[15]

However, a convention that might be applicable is that of the Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic Religious and Linguistic Minorities (1992) which states thus:

"Persons belonging to minorities have the right to participate effectively in decisions on the national and, where appropriate, regional level concerning the minority to which they belong or the regions in which they live, in a manner not incompatible with national legislation.[16]

The Ekuri people are part of the minority groups in Nigeria and in accordance with the declaration stated above which Nigeria is a signatory to, due compliance is needed. This could be the platform from which to hold Nigeria accountable for not giving a voice to a minority group which can be seen as marginalization and in every way a violation of basic human rights.

Also, the Convention on Biological Diversity has a part that could prove the illegality of the move of the State government. The provision in article 3 of the Convention on Biological Diversity state thus:

"Principle States have, in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations and the principles of international law, the sovereign right to exploit their own resources pursuant to their own environmental policies, and the responsibility to ensure that activities within their jurisdiction or control do not cause damage to the environment of other States or of areas beyond the limits of national jurisdiction" .[17] The concluding part of this provision clearly states the part of the State in minding the impact of proposed activities in such a way that the ecological integrity of the environment will not be jeopardized. Considering the extent of the proposed 20km corridor road and the potential impact on the intact rainforest that has overtime been recognized as a hotspot for many endemic species of animals and plant, the proposition of the road project without adequate impact assessment is a clear contradiction to the provision of this convention.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Carter, J. (1996). Recent Approaches to Participatory Forest Resource Assessment Rural Development Forestry Study Guide 2. Retrieved from https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/8145.pdf.

- ↑ Enuoh, O. O. O., & Bisong, F. E. (2015). Colonial Forest Policies and Tropical Deforestation: The Case of Cross River State, Nigeria. Open Journal of Forestry Nigeria. Open Journal of Forestry, 5(5), 66–79. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojf.2015.51008.

- ↑ Ogar, E. (1990). Does National Or Sub-National Law Or Policy Recognize Terrestrial, Riparian Or Marine Community Conserved Areas (Ccas)?, 1–5.

- ↑ Edwin Ogar. (2013). Nigera: A Unique Example Of Community Based Forest Management At The Ekuri Community | WRM In English. Retrieved October 17, 2017, From Http://Wrm.Org.Uy/Articles-From-The-Wrm-Bulletin/Section1/Nigiera-A-Unique-Example-Of-Community-Based-Forest-Management-At-The-Ekuri-Community/.

- ↑ CRS Forest Communities Speak Out. (2016). Retrieved from http://www.onesky.ca/files/uploads/Forest_Community_Consultation_Policy_Brief_FINAL.pdf.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Eugene Ejike Ezebilo. (2012). Nature Conservation in a Tropical Rainforest: Economics, Local Participation, and Sustainability. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Eugene_Ezebilo/publication/46268989_Nature_conservation_in_a_tropical_rainforest/links/54c9fa840cf2807dcc28656f/Nature-conservation-in-a-tropical-rainforest.pdf

- ↑ Ajake, A. O., & Abua, M. A. (2015). Assessing the Impacts of Tenure Practices on Forest Management in Cross River State, Nigeria. Journal of Geography and Earth SciencesOnline) Journal of Geography and Earth Sciences, 3(32), 95–117. https://doi.org/10.15640/jges.v3n2a6.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Mock, G., Mcneill, C., Corcoran, J., Virnig, A., Pierce, A., & Keegan, D. (2016). Climate Solutions from Community Forests Learning from Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities ii Climate Solutions from Community Forests: Learning from Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities, (2), 67–104. Retrieved from www.equatorinitiative.org .

- ↑ Menzies, N. K. (2007) Our Forest, Your Ecosystem, Their Timber: Communities, Conservation, and the State in Community-based Forest Management. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ↑ Environmental Impact Assessment Decree No. 86(1992) Retrieved November 21, 2017, from http://www.nigeria-law.org/Environmental Impact Assessment Decree No. 86 1992.htm.

- ↑ Laurance, W. F., Campbell, M. J., Alamgir, M., & Mahmoud, M. I. (2017). Road Expansion and the Fate of Africa’s Tropical Forests. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 5(July), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2017.00075.

- ↑ M. Taghi Farvar, G. B.-F. ( I. C. (2016). Concerns Regarding Impacts Of A Proposed “Super Highway” On The Ekuri Community Forest And Other Forested Environments And Communities In Cross River State, Nigeria. Retrieved From Https://Www.Iccaconsortium.Org/Wp-Content/Uploads/2016/04/Event-2016-Nigeria-Letter-From-ICCA-Consortium-On-Ekuri-Forest-Feb.Pdf

- ↑ Abang Mercy. (2017). Superhighway in Cross River Threatens To Displace 50,000 Inhabitants | Sahara Reporters. Retrieved October 18, 2017, from http://saharareporters.com/2017/03/18/superhighway-Cross-River-threatens-displace-50000-inhabitants.

- ↑ Karunwi Adeniyi. (2016). Cross River State Superhighway: The Threat Still Stands. Retrieved October 18, 2017, from http://www.ncfnigeria.org/about-ncf/item/267-cross-river-state-superhighway-the-threat-still-stands

- ↑ Shuaibu, A. (1992). UNPO: Ogoni: Nigeria Opposes Indigenous Rights Declaration. Retrieved November 20, 2017, from http://unpo.org/article/6763.

- ↑ United Nations Human Rights( Office of the High Commission). (1992). Belonging to National or Ethnic, Declaration on the Rights of Persons Religious and Linguistic Minorities. Retrieved from www2.ohchr.org/english/issues/minorities.

- ↑ Convention on Biological Diversity, United Nations, (1992). Retrieved from https://www.cbd.int/doc/legal/cbd-en.pdf.

| This conservation resource was created by Bamidele Oni. |