Course:LFS350/Projects/2014W1/T6/Report

Executive Summary

Inner City Farms (ICF) is a community based, not for profit organization that makes use of residential and institutional agricultural space to grow food. This project involved a primary analysis for the development of a one acre hop yard; the goal of the yard to provide profit for the sustainability of ICF and their active ventures. To determine the feasibility of the hop yard, we aimed to answer the following questions: what are the costs associated with the development of a one acre hop yard? What is the state of the market for the sale of fresh hops in Metro Vancouver? What factors influence the consumer choice in the food and beverage system and how does it relate to local food production? To answer these questions, we conducted a thorough literature review to determine development costs, we conducted interviews and surveys to assess the state of the market for fresh hops, and to determine the factors that influence consumer choice in the food and beverage system. The key results that arose for our first research question involved the approximate cost analysis. As for the results for research questions two and three, we determined that the status of the market would willingly accept the production of locally grown hops and lastly that the factors that influence consumer choice are somewhat inconclusive and thus the relationship between these factors and local food production is unclear. The recommendations for ICF and the community is that to improve food systems issues, educational resources should be more available to individuals in Vancouver in order to introduce them and acquaint them with these topics. Limitations of our study included the lack of detail in our survey questions, and the scope of the project also presented a limitation to the overall development of our project.

Introduction

Locally-produced food benefits local food systems by enhancing the economy, initiating positive environmental impact, and strengthening interpersonal interactions between community members and farmers (Zepeda & Leviten-Reid, 2004). What’s more, consumers benefit from the freshness and quality of said local produce (Zepeda & Leviten-Reid, 2004). The integration of community-driven initiatives into the local food system affects more than the direct consumer. Through word-of-mouth and the teaching of future generations, those that are removed and uninterested in food production will be exposed to the principles of food sovereignty and sustainability.

Several not for profit organizations have taken on the responsibility of supporting the community by educating its members on these concepts. Programs such as community supported agriculture (CSA) and community supported fisheries (CSF) have been steadily multiplying over the last few years. These programs seek to target the community’s involvement through support of local farmers and producers. Inner City Farms (ICF) is just one example of a community organization making a positive impact through said programs.

ICF is a community based, not for profit organization that makes use of residential and institutional agricultural space to grow food. (ICF, 2012) Through their farming, ICF’s goal is to provide and educate members of the community on establishing sustainable food systems. The current model that ICF operates by does not allow for an abundance of profit and hence, ICF is in need of a profit driven venture to sustain the currently active projects. Recently, the Metro Vancouver area shifted their buying power in the beer industry from large scale, mass produced companies like Molson and Labatt, to local so called ‘microbreweries.’ In 2013, ICF ran a trial with six hops plants. (Camil, personal communication, Sept. 25 2014) They were successful in producing and selling fresh hops to a local brew master and hence, the project was born.

In keeping with the values of ICF’s existing farming practices, they are looking to expand and establish a profit driven venture through the development of a hop yard. Metro Vancouver is an ideal location to grow hops because the plants require long days and direct sunlight. The mild, humid winters and relatively dry, sunny summers provide optimal growing conditions for the hops. (Warkentin, 2010) The hops that ICF grows will be available for sale to local microbreweries for the production of a specialty beer made using the fresh hops.

The purpose of the hop yard development project is to provide ICF with a breakdown of the costs associated with establishing a one-acre hop yard and a market analysis pertaining to the demand for fresh hops in the Vancouver area. Through this analysis, ICF will be able to decide if a hop yard could be a suitable means of making money to sustain and further develop their current projects. The goal of the project is to provide a source of locally and sustainably grown hops for sale to microbreweries in Metro Vancouver while bringing income to ICF.

The following research questions allowed us to view the one-acre hop yard development venture and the associated food system; each research question related to a specified boundary within the system. The first question related to the one acre hopyard farm: What are the costs associated with establishing a one-acre hop yard in Metro Vancouver? The second boundary that was identified in the hop yard’s food system was the breweries; this was the target of the second research question: What is the state of the market for the sale of fresh hops in Metro Vancouver? The third research question related to the largest boundary that was identified, consumers within Metro Vancouver: What factors influence consumer choice in the food and beverage system, and how does it relate to local food production?

Inner City Farm Hop Yard Food System

Research Methods

To answer the stated research questions we collected both quantitative and qualitative data. Initial data collection for question one was qualitative via internet-based research. It was collected to determine a proposed design for the hop yard and a list of materials that would be required to develop it. We also conducted interviews with local (within Metro Vancouver) breweries to gather information related to the kind of hops that have been most desirable during past production of fresh hops beer. Quantitative data was also gathered, via internet search engines, to determine the cost of the materials required to build the hop farm. This information was used to calculate the overall cost of the materials required to establish a one acre hop yard. The data was compiled to generate a comprehensive plan that included all associated costs to build and plant a one-acre hop yard.

Quantitative data was gathered through internet-based searches to determine the number of breweries in Metro Vancouver that have made a fresh hops beer in the past, as well as the number of local breweries that currently produce fresh hops beer. This data was used to determine which breweries would be approached for interviews to answer the second research question. Qualitative data was gathered via interviews that were conducted (via email and personal meetings) with various brewmasters that had previously made fresh hops beer. The interview was structured to gather data regarding fresh hops beer production, current use of fresh hops, and any future plans for expansion of fresh hops beer production. We analyzed our data to determine the status of the fresh hops market in Metro Vancouver. This data was used to help conclude whether or not a for-profit hop yard would be able to sustain ICF’s current projects.

For the third research question, qualitative data was collected in the form of a Brewery and Metro Vancouver population surveys to determine if the community would value and support urban farming of fresh hops for the production of fresh hops beer by local breweries.The purpose of creating two surveys was to include the opinions of the general public and those with a more extensive background in the beer production process. This was done to achieve a representative sample whose results could be generalizable to the population and to avoid bias. With reference to Larossi (2006), the survey questions were reviewed and revised to ensure relevancy to the survey objective. The Metro Vancouver population survey was administered by our team members in the Commercial, Point Grey and Downtown neighbourhoods to generate a representative sample of the Metro Vancouver area. Similarly, the Brewery survey was to be self administered at the breweries that participated in the interviews. The surveys would have been placed inside the bill fold that is presented to customers to fill out as they pay. However, this was not possible because the breweries did not agree so our team administered the surveys at “Beer Creek,” a neighbourhood surrounded by local breweries, to catch patrons of the breweries. Once the surveys were returned, the data was graphed and a statistical analysis was conducted.

As presented above, our group achieved our community-based learning through the interviews conducted with breweries (via email and personal meetings) and survey administration. Although, it was not a “typical” community-based learning project, it was still as an enriching experience to become acquainted with the hops/local beer system. Immersing ourselves into the community while conducting the surveys and interviews, we gained insight into the ethical responsibility needed to approach our community; showing respect for peoples opinions and remaining transparent by explaining the objectives of our project helped us to acquire reliable and unbiased data.

Overall, our research approach evolved dramatically from the start of the project to its completion. We started with one broad question “Is it feasible to develop an economically successful and sustainable hop yard on a one acre plot of land within Metro Vancouver?”. We quickly learned that the scope of this question was out of our capabilities given our previous experience with research and the time constraints. With some adjustments and continued communication with our community partner we ended up with the three research question that were previously stated. (View Appendix: A for further details on the research evolution)

Results

Table 1: Breakdown of Costs Associated With Developing a One-Acre Hop Yard

| Description of Infrastructure | Cost of Infrastructure |

|---|---|

| Land prep | $26 |

| Post Holes - digging | $312.50 |

| Post Holes – placement | $750 |

| Poles – field | $1590 |

| Poles – end | $1640 |

| Post ground anchor | $650 |

| Wire | $1000 |

| Hardware | $500 |

| Hop Plants | $3000 |

| Labour (planting) | N/A (volunteers) |

| Labour (management) | $240 |

| Irrigation | $1500 |

| TOTAL | $11208.50 |

(Sirrine et al, 2010)

Population Survey Findings:

Please refer to Appendix A for a complete list of the survey questions that were asked to the Metro Vancouver and Brewery sample populations as well as figures that were referred to but not displayed in this section.

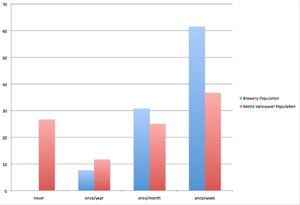

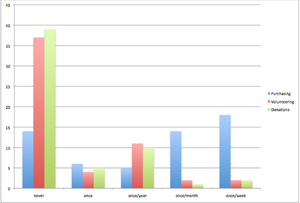

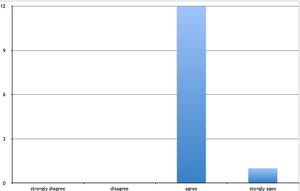

The survey results from question 2 show that out of the sample of 60 people surveyed, in Metro Vancouver, 15% of individuals never purchase products derived from urban farming programs, 6% have participated once, 5% participate once a year, 14% participate once a month and about 17% participate once a week. In terms of volunteering for urban farming initiative to show support, 37% have never volunteered, 4% have volunteered once, 11% participate once a year, 2% participate once a month and 2% participate once a week. The survey also indicated that 39% of individuals have never donated to urban farms, 5% have donated once, 10% donate once a year, 1% donate once a month, and 2% donate once a week. Figure 3 shows that, out of the 60 individuals, the majority of the population has never contributed to urban farming practices .

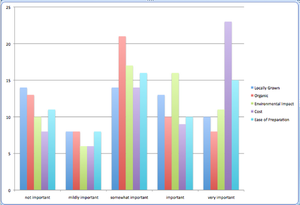

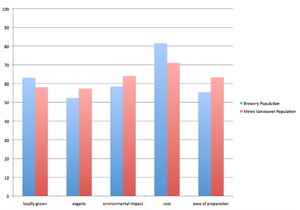

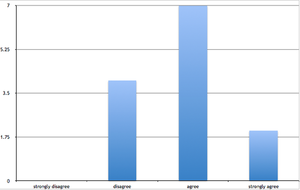

As shown in Figure 5, cost is the most influential factor with approximately 75% of the population listing it of significant importance.

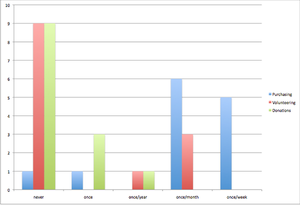

Figure 6 shows that approximately half of the Brewery and Metro Vancouver populations have never participated in practises related to urban farming. Just over one tenth of each of the respective populations are active participants in the urban farming community.

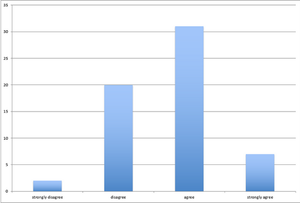

The survey results for question 3 showed that 63% of participants either agree or strongly agree that there are enough outlets in Vancouver to support local farming. 33% of the population said they disagree with the presented statement and only 6.7% said they strongly disagree the presented statement.

Results from question 4 showed that less than half (43%) of the participants know of any individuals that grow food in Metro Vancouver. From those who knew someone that grows food locally, 42% are their family and friends, 29% are school farms, and another 29% are community gardens.

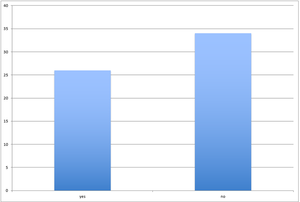

As seen in figure 9, the results from question 5 show that out of the sample of 60 people surveyed in the Metro Vancouver population, less than half (43%) were not aware of what hops were produced for while the remaining 57% did know that hops were used to brew beer.

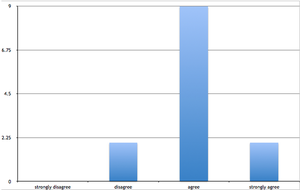

The results from question 6, as displayed in figure 10, show that out of the 34 participants who knew what hops were grown for, 54% agreed and 27% strongly agreed that urban farming of hops would have a positive impact on the local food, health, nutrition and community economic development and agriculture. While 19% disagreed and did not see urban farming of hops having a positive impact on the local food system.

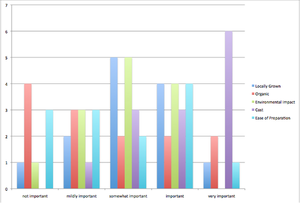

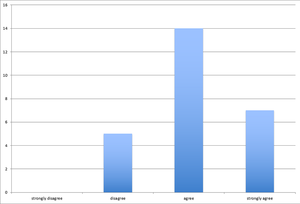

The Brewery survey results from question 3 as shown in figure 11 show that around 69% of participants agree or strongly agree that there are enough outlets in Metro Vancouver to support local farmers. 31% disagree with this statement, but no one strongly disagrees.

As displayed in figure 12, the results from question 4 show that no one disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement that urban farming of hops would have a positive impact on the local food, health, nutrition, and community economic development and agriculture. 92% agreed and 8% strongly agreed with this statement.

The results from question 5 shows that 15% of population would not prefer to drink beer made from locally grown hops. 69% agreed and 15% strongly agreed that they would prefer to drink beer made from locally grown hops.

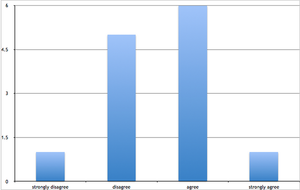

The results from question 6 shows that approximately 7.7% of the sampled population strongly disagrees and 38.5% disagree that they would be willing to pay more for beer produced using local hops. While 46.2% agree and 7.7% strongly agreed with the specified statement.

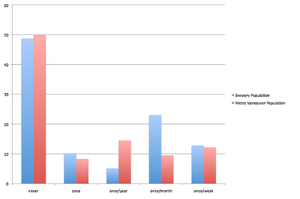

As displayed in figure 15, over half of the Brewery population and approximately a third of the Metro Vancouver population purchase locally produced beer at least once per week. About a quarter of the Metro Vancouver population has never purchased locally produced beer and another quarter of the same population purchases it at least once/month.

Brewery Interview Results:

Four breweries that were contacted responded to the questionnaire. Due to the sensitive nature of the information, the breweries will simply be referred to as brewery A, B, C, and D. A fifth brewery declined to participate in this project. Breweries A, C, and D all indicated fairly consistent usage of fresh hops per litre of beer produced at 0.05 pounds. Brewery B uses significantly more, 0.5 pounds per litre. The desired variety of hops varies depending on the style of beer that each brewery produces however, the most commonly sought after hops for fresh hops beer are centennial. All of the breweries require the use of a hop back to make fresh hops beer. The price of hops varied dramatically from ten to eighteen dollars Canadian per pound. Only one brewery, brewery B, found the price of fresh hops to be reasonable. Every brewery indicated a different amount of fresh hops to be purchased next year: brewery A 500 pounds, brewery B 400 pounds, brewery C 100 pounds, and brewery D 200 pounds. Half of the breweries indicated plans to expand their production of fresh hops beer. Brewery A has an existing partnership with an unnamed local farmer and breweries B and C have existing partnerships with Sartori Cedar Ranch in Chilliwack. Brewery D does not have an existing partnership; they are interested in developing a partnership with ICF.

Discussion

From our results, the following data was significant to successfully answer the three research questions. Firstly, we determined that, in order for the hopyard to be a beneficial addition to ICF’s project, it would need to generate profit in 3-5 years. Building a hopyard requires a large start up capital investment however; given that we were able to establish a potential business partnership, we feel that this project could proceed and generate profit. This profit is essential to fund ICF’s projects and pay employees to sustain their currently active programs as well as provide money to expand.

From our interviews with the breweries, we determined that the market status for a local hop yard is a promising one. This is supported by the fact that the four breweries indicated in their interviews that they intend on continuing or expanding their beer production and specifically their production of fresh hops beer. Brewery D, also indicated that they would be interested in developing a partnership with ICF. This action shows their interest, intended expansion and commitment to the development of fresh hops beer. Determining the status of the fresh hops market was significant because it allowed us to develop a potential partnership between ICF and a local brewery. This partnership could result in a profitable hopyard venture thereby providing the necessary funds to support and sustain ICF.

Finally, we found that the factors that influence the consumer choice in the food and beverage system were highly variable. It goes without saying that consumer preference is largely driven by a number of factors. The population survey--and especially its first two questions--sought to get an idea of how consumers in Metro Vancouver consider said factors when purchasing food. Locally-grown and organic produce have become very popular but are considerably more expensive than conventional alternatives. A link is often drawn between environmental impact and the origin of the produce (read transport and storage costs), whereas organic produce is generally perceived as being healthier. ‘Ease of preparation’ is often associated with cheaper processed foods, though the purchase of these products may be seen as the easiest to some. Therefore, it is essential to note consumer subjectivity and how their lifestyles may influence their interpretation of each factor, especially when polling from a number of neighborhoods, each presenting a different socio-economic and cultural context.

A number of relationships may be drawn from the results of question one. For instance, organic certification was the least important factor, showing an inverse relationship to cost, which was the most important. Consumers ranked environmental impact and locally-grown as ‘somewhat important’, considerably higher than organic. Does this mean that consumers are failing to acknowledge or commit to the positive environmental impacts of organic farming? Likely, though pro-environmental choices may be made without purchasing organic-certified produce; locally-grown produce is good for the environment without being organic. Therefore, it may be that people are making purchases with the environment in mind, just that they would prefer to do so by buying local, not organic. This makes sense due to the widely accepted fact of global warming and the importance of reducing emissions versus the highly debated organic label. What’s more, local food is often cheaper, which likely translates as being of higher value to the consumer.

Question two explores whether the consumers partake in producing and/or generating food by way of urban farming. The majority have not made a donation to an urban farming initiative; an equal amount of those surveyed have never volunteered. Those that have volunteered continue to do so. Therefore, it may be beneficial to encourage community members to become active with an urban farming project directly as opposed to asking for one-time monetary donations. Additionally, the vast majority of consumers surveyed purchase urban produce on a regular basis. Offering an opportunity for them to discover the origin of what they are purchasing in return for some of their time may be an effective way of educating and potentially enlisting consumers.

The results of question three showed that the majority of people feel that there is enough outlets for them to access to local food products. It is likely that those people who do not feel that adequate access exists are limited by some extenuating factor such as location, means of transportation, or personal/family income. The results of question four provide a possible explanation for the results gathered by question two; the majority of the population feels that opportunities to participate in urban farming are limited in the Metro Vancouver area. Less than half of the population knew of any individuals or organizations that engage in local farming practises. This limits their chances to actively participate in urban farming. We discovered that individuals were made aware of urban farming practises through school farms or community gardens which leads us to believe that the facilities are there, people just are not making the effort to engage with the organizations that are running them. Therefore, it might be helpful to continue advocating urban farming through education in schools and community houses like those that were partnered with other groups is LFS 350 to target a greater majority of the population.

It was evident from the responses that there was a disconnect between the community and one of objectives of our project because almost half of the population did not know that hops were used to brew beer. This showed that people are not acutely aware of the scope of the food system in their community. It also provides an opportunity for farmers, industry members, and academics to teach people of their role in the food system to connect them with the local beverage production industry. This question was especially important because it provided insight into how aware people are of the complexity of the food system. The majority of people who are already educated in the beer production process felt strongly that local hop production would contribute to the overall sustainability of the food system in Metro Vancouver. So even though a majority feel that urban farming of hops is beneficial, an almost equal number of people did not know of hops usage in the first place. This result further supports the need for more education in the community. It is likely that if more people were aware of the extent to which the local community uses hops, they too would feel strongly that local production would enhance food system sustainability and hence, food security.

The Brewery population survey led us to draw similar conclusion to those seen from the Metro Vancouver population survey. Most people felt there were enough outlets for them to access local food products with no one indicating that their access was restricted. Additionally, urban farming of hops was perceived to have a positive impact on the local food, health, nutrition, and community economic development and agriculture. The positive responses shows that the Brewery population is likely more aware of the benefits of urban hop farming. We are hopeful that this would translate into a higher percentage of the population willing to support and purchase beer products made using locally grown hops and our results show that they would; the Brewery population prefers beer made from locally grown hops and the majority of patrons would be willing to pay more for the premium product. These questions are very important because they show that there is a demand in the current market for beer produced using locally grown products. The results of the surveys were significant because they showed that a large portion of the Metro Vancouver community is either uneducated or unaware of the practices of urban farming. This indicated that more needs to be done in Vancouver to educate individuals about the practice of urban farming and the benefits such program have on local food system sustainability.

Many of the limitations of our research project involved our surveys. Our survey answers did not provide explanations for individuals answers. Additionally, there was a total of 80 surveys, and thus the data compiled was fairly small. With more time and resources, the survey populations could have been larger, and more representative of Metro Vancouver. We were also limited by the scale and broadness of our study. We worked efficiently as a group, however, the difficulty arose when we tried to narrow the topic down to feasible research questions.

The connections from our CBEL project and LFS 350 arose through our research methods, and community learning. We developed our project through a mixed methods approach as presented in class (Creswell, 2003). We also discovered that community engaged learning allowed us to obtain information about the Vancouver population and their knowledge regarding urban farming practices and their purchasing trends. After participating in class with individuals and academics who are aware of food system sustainability and food security issues, it was interesting to explore what the population knew about these topics. This highlighted the importance of working with the community to access land and resources to achieve the goals of urban farming initiatives. We also determined that the overhead of urban farms is very expensive and there is often little profit made. The food system is a multifaceted entity; improvements in one area are not able address food security alone. When addressing food systems we determined that it is important to consider cost, policy, infrastructure and other factors that are relate and thereby improve food security in the local community.

Conclusion

The community based research contributed to the overall development of the CBEL project as it forced us to venture into the community with no preconceived notions, as well as an objective view of the hop yard situation. Consequently, we were able to experience the community for what it really is, instead of seeing it how we want to see it. In conclusion, we determined that Vancouver lacks the knowledge in the area of food system sustainability and the practices of urban agriculture. We suggest to improve this issue, educational resources should be more available to individuals in Vancouver in order to introduce them and acquaint them with these topics. In terms of Inner City Farms, the development of a hop yard with a local business partnerships may publicize ICF and therefore create a better awareness of urban farming practices within Metro Vancouver.

Works Cited

Works Cited:

- Creswell, John W. (2003) Research Design Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. Retrieved from: https://connect.ubc.ca/bbcswebdav/pid-2365918-dt-content-rid-9146590_1/courses/SIS.UBC.LFS.350.001.2014W1.36591/2003_Creswell_A%20Framework%20for%20Design.pdf

- Larossi, G. (2006). The power of survey design: A user's guide for managing surveys, interpreting results, and influencing respondents. World Bank Publications.

- Inner City Farms. (2012). Meet your urban farmer. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CT-L03T_68A

- Kneen, R. (2002). Small Scale and Organic Hops Production (p. 15). Sorrento.

- Sirrine, Robert J., Rothwell, Nikki, Lizotte, Erin, Goldy, Ron, Marqui, Steve (2010) Sustainable Hop Production in the Great Lakes Region Retrieved from: http://www.uvm.edu/

- The Great Dominion: Studies of Canada, 1895. (2010). In J. Warkentin (Ed.), So Vast and Various: Interpreting Canada's Regions in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (p. 219). McGill-Queen's Press.

- Zepeda, L., & Leviten-Reid, C. (2004). Consumers’ Views on Local Food. Journal of Food Distribution Research, 35(3), 5-5. Retrieved November 1, 2014, from http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/27554/1/35030001.pdf