Course:GEOG352/Transportation in Lagos, Nigeria

Transportation is the “live wire” of many urban cities.[1] The primary functions of transportation are to facilitate the movement of people and goods and to provide access to land use activities located within the service area.[2] Transportation infrastructure in the global south is an interesting area of study because current global trends indicate that more than 90% of urbanization growth occurs in ‘developing’ countries which places intense pressures on urban infrastructures, particularly transportation. The effectiveness of transportation is one factor that helps determine the accessibility of resources for the city’s inhabitants. Urbanization involves an increased numbers of trips in urban areas thus, inefficient transportation in the global south can compromise the economic growth and hinder spatial and economic inclusivity. Within a rapidly urbanizing city, there are two types of economies which exist on a spectrum of the formal and informal. The informal sector defines activities, usually economic, within a city that do not operate under government regulations; the informal economy is generally not counted in the country's formal economic calculations for GDP. Informal economies emerge mostly from contexts of high rates of unemployment, poverty, and gender inequality.[3] People often enter the informal economy due to the lack of access to formal methods of income generation. In contrast, the formal economy is characterized by employment that operates within a government regulated framework. Workers within the formal economy benefit from legal rights and protections overlaid by the government.

Infrastructure of the city is largely affected by the formal and informal avenues of transportation. The accessibility of formal modes of transportation affect the growth and development of the informal sector, and vice versa. Therefore, inefficient transportation tends to create lucrative opportunities for workers to earn money through the unregulated, informal sector. The prominence of the informal sector in most African economies, for example, stems from the opportunities it offers to the most vulnerable populations such as the poor migrants, women and youth.[4] Even though the informal sector is an opportunity for generating reasonable incomes for many people, most informal workers are without secure income, employments benefits, and social protection.[5] This explains why informality often overlaps with poverty.[6] In countries where informality is decreasing, the number of working poor is also decreasing and vice versa. In this way, enacting good transportation infrastructure and policies can positively regulate the informal sector and create room for informal transportation workers in the rapidly growing economy of mega-cities.[7]

Overview

Why Lagos

The prominence of the informal sector specifically in Lagos, Nigeria, a typical sub-Saharan metropolitan city, can be used as a good case study for other nearby regional cities because of shared characteristics. A world renowned mega-city of 21 million, Lagos' population is expected to double by 2050, which will make it the 3rd largest city in the world. [8] Similarly with other urbanizing cities of the global south, the existing infrastructure within Lagos is an important component to citizens’ daily lives. In order to get basic access to the city’s resources, the city’s infrastructure, namely its transportation system, must adapt and develop in accordance to population growth. Lagos’s transportation system is a crucial tool that can maximize its economic gains and meets its growing demands for movement from the rapid urbanization taking place.

Informal vs Formal Economy and Transport

The informal economy, and by extension the informal modes of transportation, in Lagos exists as a consequence of bad structural pattern of growth and unplanned population growth. Historically, the incompatibility of Lagos’s formal transportation system created an economic avenue in the informal sector for entrepreneurial migrants to make a living or for those who could not afford the standard formal transportation. Lagos as a commercial and industrial nerve centre of Nigeria has the common problems of traffic congestion.[9] As the city urbanized and population grew, the government made plans to upgrade the city’s infrastructure, and invested in projects to reconstruct proper modes of formal transportation. The effect of these plans on the informal sector provides and interesting avenue to observe the effects of these plans on informal transportation workers and users.

BRT and LAMATA

Understanding how transportation technology influences the informal sector and local citizens is fundamental for establishing policies aimed at sustaining desirable levels of mobility and accessibility in light of increasing travel growth and traffic congestion.[10] In 2008, the government aimed to decrease the worst areas of congestion in Lagos with the creation of the Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system.[11] The responsibility for implementing the BRT project fell to the Lagos Metropolitan Area Transport Authority (LAMATA) which was founded in 2002. Prior to the establishment of the BRT, most transport around Lagos was dominated by informal transport minibuses (also known as danfos). As such, the BRT and LAMATA sought to formalize overall transportation as a way to phase out the informal sectors.[12]

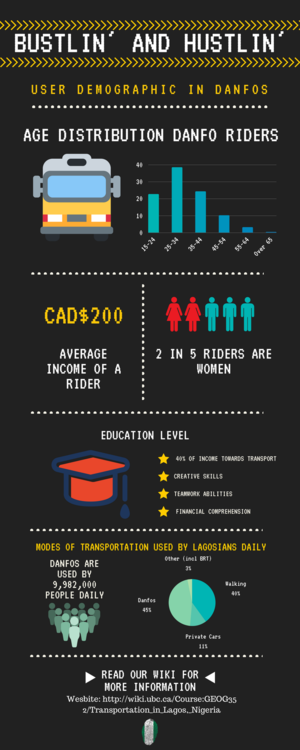

In practice, although the BRT did reduce traffic congestion and reduce the ridership of informal transportation, however, it’s important to focus on the socioeconomic disparities of who gets to benefit from these kinds of newly formalized transportation within Lagos. For example, socioeconomic factors including age, gender, marital status, level of education, employment status and types, location of place of work, and household monthly income affect the everyday decisions people make.[13] Studies have discovered that the average user of the BRT was male, aged 32.9 years, with an average income of ₦57,140.55 (roughly 200 CAD), household size of 4.9 persons, having acquired 12.8 years of formal education, traveling 25.5 kilometres daily for almost 2 hours on public transport on an average cost of ₦712.83 (roughly 2.5 CAD).[14] For those who are outside this demographic, their transportation choices may fall to more affordable means in the informal sector. In recent years, the government-implemented formalization of Lagos’ transportation system has affected those dependent on the informal modes of transportation, whether it be for employment or for more accessible transportation. Lagos makes an interesting case study for how infrastructure of transportation adapts in a city with a booming economy and population.

Case Study of Theme/Issue

Problem

The danfo bus system has been widely been criticized by Governor Ambode, who argues that their aesthetic falls short of the modernity that the term “megacity" implies.[15] Danfos have been blamed for the massive congestion of Lagos, as well as for being a space of violence especially for women and poorer strata of the population. 39.7% of women use danfos as their main method of transportation, a number which increases to 54% once they are married, while 81% of users have a secondary schooling background, higher than the Nigerian average.[16] The poor maintenance and lack proper bus stop infrastructure for danfos have been at the roots of congestion and high mortality on the streets of Lagos.[17] Pokafor Ifeoma, in her study, found that 59% of drivers had poor knowledge of road signs, with only 1% of drivers knowing the appropriate steps in getting a driver license.[18] Although these issues are undeniable, danfos provide a form of transportation to 9 million of people per day representing 45% of all transport and a form of livelihood for newcomers to Lagos (which is around 86 per hour).[19][20]

Situations

The government ban on danfo drivers puts them into a precarious economic situation, perhaps, more importantly, it puts the transportation network of Lagos in jeopardy. The government is tries to keep up with the demand for new buses for the BRT system, as well as overall infrastructure. On the other hand, there is no evidence that suggests that the switch will be accepted by the population of Lagos. To fund these plans, bus fare increased between 20% to 67% in 2017, making formalized transportation harder reach, especially since transportation costs an average of 40% of a Lagosian's income per month.[21][22] Rather, the banning of danfos is not being met equally by a sudden increase in service or accessibility of the formalized BRT system. Therefore, the decision to ban danfos seems to be based on the perception of what a megacity should look like, rather than through consideration of the particular local transport culture of Lagos. Governor Akinwunmi Ambode often compares Lagos to other world cities without looking at the local urban context.[23] This reflects a particular biased approach by the government. Although Ambode has stated that there will be no job loss, many citizens have doubts about the realities of such promises coming to fruition.

Solutions

Government intervention in the provision of infrastructure has widely been seen as a net benefit. Scholars, Banister and Berechman, have demonstrated that infrastructure usually aids economic development and increases efficiency; this has been a main motivation behind the building of new infrastructure.[24] However, by banning danfos there is a particular leap into the unknown. The government wants to introduce 5,000 new regulated buses into the streets of Lagos with new pedestrian walkways and bus stops in order to increase safety and decrease traffic congestion.[25] Presently, only 1% of people use the regulated bus system with no supporting evidence to prove that Lagos’ new regulated buses would be accepted.[26] Perhaps instead of a ban of danfos, the government should aim to formalize the danfos system. This would increase job security, perhaps create better service through licensing power, and can filter appropriate operators of danfos while retaining the strength of the danfo system (which is the semi-formal nature of the enterprise). The renovation of Lagos’ infrastructure already benefits the transportation and the danfos system as a whole, with congestion and mortality naturally decreasing from more effective infrastructure.

Direct and Indirect Impacts of Danfos in Lagos

Issues with informal danfos are directly relevant to Lagos because the city buzzes with "75,000 danfos and sustains the movement of over 16 million Lagosians daily. Each danfos with a carrying capacity of between 8 and 25 passengers."[27] This contributes to not only the formal but also the informal economy of the city. With Lagos’ booming population, we can predict the total transport usage to increase as greater numbers of people have access to public transport. Danfos have an irreplaceable role in the urban city ecosystem and have a defining place in the daily decisions of Lagosians. The urban population spends about 20% of their disposable income to use the danfos rides, meaning they would be directly affected if the trips became more expensive. The removal of danfos would affect the daily interactions citizens have with informal salesworkers and vendors. Transport demand generated by the economy is an important factor in how movements of space, mobility, and accessibility are expressed.[28] Removing the cheaper informal danfos and introducing the more expensive BRT would alter the accessibility of movement through the city. In the study done by Taofiki Salau, he found that majority of those that ride danfos are working class men, with household of 4-6 persons. If their trips to work require them to spend more money it would have a direct effect on the overall household income. On the other hand, danfos also seem to be risky spaces for both the driver and passengers spaces as 75% of the crashes are due to the human error.[29] This is because either the drivers are partially blind, are hypertensive, or are inhibited by a drug called paraga. However, this is the result of the relatively few full-time jobs available in Lagos, and thus danfos driving becomes attractive to those that are seeking employment.

Urban transportation is less about the material object and more about how they constitute the social fabric of a city. Danfos are more than metal containers that move people from one side of the city to the next. Taking a danfos ride is to move with epistemologies and lifeways that one operates with daily in Lagos. Agbiboa defines danfos as being "mobile bodies of meaning" in how they contribute and shape the lives of danfos drivers and how they identify themselves. For the passengers, the slogans written at the back of danfos are "themselves an effective way to initiate conversations inside the danfos".[30] This means that danfos are spaces of interaction and dialogue. It is important to remember that "spatial practices are tactical in nature."[31] Through these slogans the danfos workers develop a unique competitive edge through their choice of slogans. If the danfos were to be formalized, these unique spaces of resistance and expression of individual identity would be replaced. In other words, the Eurocentric idea of modernity is a narrative of progress that Governor Ambode operates with, and it does not leave room for local conversation, it does not bring with it a unique Lagosian touch.

Lessons Learned

Danfos were originally created in the absence of adequate transportation infrastructure and provided opportunities of self-employment for those who believed that government jobs were unrewarding and not secured, as a result of structural adjustment policies (SAPs). [32] The system of danfos shaped social interactions and structure which have added to the uniqueness of Lagos’s transportation system. In trying to remove danfos from the infrastructure of the city, the government inadvertently undermined the existence of social structures that emerged from the creation of danfos.

Like many urban cities in the global south, Lagos suffers from socio-economic inequalities which underlie the safety concerns of its informal transportation. Gender and wealth disparities limit the freedom and safety of those who wish to use formal public transportation. As we discovered from our case study, the demographic of users of the BRT are mostly adult men who are economically well off. Others who do not fit into this demographic seek employment in the informal sector, which often includes services as informal transportation operators.

Like author, Robert Cervero wrote, “safety problems associated with transportation services are symptomatic of wider economic problems that affect all of Africa’s economy.”[33] The safety of danfos are a major concern. Rightfully so, these concerns and differences should be addressed by Lagos’ government but in a way that includes the informal workers instead of seeking the complete erasure of danfos. For example, basic transportation improvements, like dedicated lanes for danfos, alongside financial support, like the provision of micro-credit to encourage upgrading of danfos, will go a long way towards inclusion of informal workers in Lagos’ robust economy. Thus, an alternative multi-pronged approach facilitates upgrades in transportation infrastructure in the near term but also pays attention and sensitivity to longer term issues such as poverty, gender inclusion, informality and culture. Danfos have become a part of Lagos urban culture and complete eradication of the system would be a cultural loss to the local urban community. Other countries with a large informal transportation infrastructure such as Bangkok, São Paulo, Manila, and Jamaica can hopefully also consider a more multi-pronged approach to transportation improvements.

References

- ↑ Agarana, M., Owoloko, E. and Adeleke, O. (2018). Optimizing Public Transport Systems in Sub-saharan Africa Using Operational Research Technique: A Focus on Nigeria. [online] Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2351978916302517 [Accessed 2 April. 2018].

- ↑ Ibid, see 1.

- ↑ Ilo.org. (2018). [online] Available at: http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_norm/---relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_218128.pdf [Accessed 2 Apr. 2018].

- ↑ African Development Bank. (2018). Recognizing Africa’s Informal Sector. [online] Available at: https://www.afdb.org/en/blogs/afdb-championing-inclusive-growth-across-africa/post/recognizing-africas-informal-sector-11645/ [Accessed 2 Apr. 2018].

- ↑ Ibid, see 4.

- ↑ Ibid, see 4.

- ↑ Falcocchio, JC, Levinson, HS (2015) Road Traffic Congestion: A Concise Guide Chapter 2 How Transportation Technology Has Shaped Urban Travel Patterns Springer International Publishing

- ↑ World Population Review (10/20/2017) "Lagos Population 2018" http://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/lagos-population/

- ↑ Ibid, see 1.

- ↑ Ibid, see 7.

- ↑ Lagos goes 'Lite' with BRT. (2009). Civil Engineering : Magazine of the South African Institution of Civil Engineering, [online] 17(8), pp.23-24. Available at: http://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/docview/221185740?accountid=14656 [Accessed 2 Apr. 2018].

- ↑ Ibid, see 11.

- ↑ Salau, T. (2015). Public transportation in metropolitan Lagos, Nigeria: analysis of public transport users’ socioeconomic characteristics. Urban, Planning and Transport Research, [online] 3(1), pp.132-139. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21650020.2015.1124247 [Accessed 2 Apr. 2018].

- ↑ Ibid, see 13.

- ↑ Vanguard.(2017) “Ambode Insists on Removing Yellow Buses (Danfo) from Lagos Roads.” Vanguard News. Available at: www.vanguardngr.com/2017/02/ambode-insists-removing-yellow-buses-danfo-lagos-roads/. [Accessed 3 Apr. 2018]

- ↑ Ibid, see 13.

- ↑ Ifeoma, Pokafor, et al. (2013) “Knowledge of Commercial Bus Drivers about Road Safety Measures in Lagos, Nigeria.” Annals of African Medicine, vol. 12, no. 1, 2013, p. 34., Available at: http://go.galegroup.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/ps/i.do?p=HRCA&u=ubcolumbia&id=GALE%7CA324869607&v=2.1&it=r&sid=summon. [Accessed Apr 3 2018]

- ↑ Ibid, see 17.

- ↑ Mobereola, Dayo. 2009 “Lagos Bus Rapid Transit Africa’s First BRT Scheme.” SSATP Discussion Paper No. 9: Urban Transport Series. Avalaible at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/874551467990345646/text/534970NWP0DP0910Box345611B01PUBLIC1.txt [Accessed 3 Apr. 2018]

- ↑ Kumolu, Charles, and Prince Okafor. (2017) “86 Migrants Enter Lagos Every Hour.” Vanguard News. Available at www.vanguardngr.com/2017/02/86-migrants-enter-lagos-every-hour-ambode/.[Accessed 3 Apr 2018]

- ↑ Agency Report. (2017) “Lagosians to Pay 20 to 67 per Cent More for BRT, LAGBUS Fare from March.” Premium Times Nigeria Available at: www.premiumtimesng.com/regional/ssouth-west/223389-lagosians-pay-20-67-per-cent-brt-lagbus-fare-march.html. [Accessed: 2 Apr 2018]

- ↑ Oxford Business Group (2013) “On the Road.” Report: Nigeria 2013, by Oxford Business Group, p. 253. Available at: https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/nigeria-2013 [Accessed: Apr 3, 2018]

- ↑ Vanguard. (2017) “Phasing out Danfo Buses Will Create More Jobs than Losses- Ambode.”Vanguard News, Available at: www.vanguardngr.com/2017/05/phasing-danfo-buses-will-create-jobs-losses-ambode/. [Accessed: 3 Apr 2018]

- ↑ Banister, David, and Yossi Berechman. (2001) “Transport Investment and the Promotion of Economic Growth.” Journal of Transport Geography, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 209–218. Available at: https://www-sciencedirect-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/science/article/pii/S0966692301000138 [Accessed Apr 03 2018].

- ↑ Lagos State Government. (2018) “BUHARI COMMISSIONS IKEJA BUS TERMINAL .” Lagos State Government, Lagos State Government. Available at: lagosstate.gov.ng/blog/2018/03/29/buhari-commissions-ikeja-bus-terminal/. [Accessed Apr 03 2018]

- ↑ Mobereola, Dayo. 2009 “Lagos Bus Rapid Transit Africa’s First BRT Scheme.” SSATP Discussion Paper No. 9: Urban Transport Series. Avalaible at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/874551467990345646/text/534970NWP0DP0910Box345611B01PUBLIC1.txt [Accessed 3 Apr. 2018]

- ↑ Agbiboa, D. E. (2017) “Mobile bodies of meaning: city life and the horizons of possibility,” The Journal of Modern African Studies, Cambridge University Press, [online] Available at: DOI: 10.1017/S0022278X1700012X (Accessed: 10 February 2018)

- ↑ Ibid, see 13.

- ↑ Ibid, see 27.

- ↑ Ibid, see 27.

- ↑ Ibid, see 27.

- ↑ Agbiboa, D. (2016). ‘No Condition IS Permanent': Informal Transport Workers and Labour Precarity in Africa's Largest City. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 40(5), pp.936-957.

- ↑ Cervero, R. (2000). Informal transport in the developing world. Nairobi: United Nations Centre for Human Settlements (Habitat).

| This urbanization resource was created by Course:GEOG352. |