Course:GEOG352/Food Security in Kigali

Introduction: Food security in the Global South

As defined by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), food security is achieved when “all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life” [1]. Food insecurity is a global phenomenon impacting over one billion people around the globe today[1]. A combination of urban poverty, suboptimal food distribution systems, and an inadequate food supply from rural areas make food security particularly problematic in cities.

Cities, particularly in the global South, often struggle to develop the infrastructure necessary to feed their rapidly growing populations. Outdated agricultural practices, lack of available arable land, and the variable effects of climate change lead to food production shortages, while inefficient distribution systems drive up food prices. Food insecurity has detrimental social, economic and political consequences leading to lack of social cohesion, reinforced gender inequality in addition to stifling economic growth and poverty reduction. It is also accompanied by a significant amount of health risks, with food insecure populations often facing a lack of dietary diversity, chronic diseases, and malnutrition, especially among vulnerable and marginalized populations.

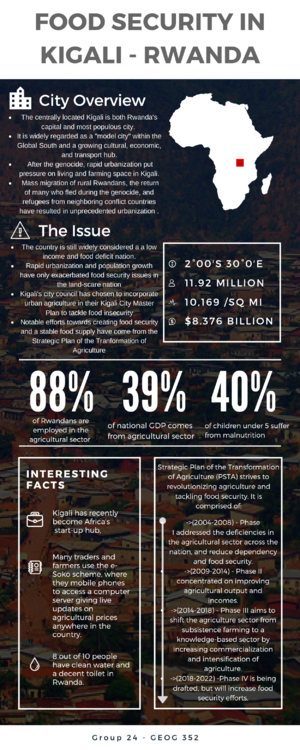

Building sustainable and food secure cities has been identified as a critical development goal for the 21st century, as food insecurity impacts all aspects of the functioning of a society. The city of Kigali in Rwanda will be used as a case study to represent the impacts of food insecurity and how the Strategic Plan for Transformation of Agriculture (PSTA) was implemented to address food insecurity in Kigali and across the country[2].

Overview: Food security in Kigali, Rwanda

Food security, as it is conceptualized today, is concerned with food accessibility on a household and individual level. The concept of adequate food is measured in both quantitative terms (e.g. caloric intake) and qualitatively (e.g. safety, variety, cultural appropriateness). The human rights dimension of food security has only recently been accepted by the international community; however, it is not a new concept - it was first recognized in the UN Declaration of Human Rights 1948. World Food Summit delegates in 1996 paved the way for a rights-based approach to food security with their formal adoption of the Right to Adequate Food (FAO Policy brief). As defined by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), food security is achieved when “all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life”[1]. Sustainable household food security depends on the availability of an adequate food supply and on the means of a household to acquire the needed food[4]. Although barriers to food security are multifarious, food insecurity is largely attributed to insufficient financial resources[5].

Urbanization can influence almost every aspect of food consumption and production in a society. A significant difference, in terms of food accessibility, between rural and urban populations is that people in rural areas have the ability to produce their own food, while city dwellers are more dependant on food purchases. Additionally, those residing in an urban context have a greater dependence on processed foods and on the market system[4]. Thus, monetary income and employment are often prerequisites for being food secure. Unfortunately, most urban dwellers, especially those in developing countries, are at a high disadvantage with limited purchasing power, as the majority are employed in informal sectors. Two decades ago in urban sub-Saharan Africa, employment in sectors that paid regular wages accounts for less than 10% of total employment[4].

Rwanda’s recent past has been characterized by numerous unsustainable approaches to food security, exacerbated by the collapse of their coffee industry in the 1980’s and again by the genocide in 1990. The genocide led to the internal displacement of over 15% of the population and over 2 million fled the country[6]. As the majority of the population made its earnings from agriculture, the displacement of three quarters of the farmers caused harvest of that season to fall by half, leading to severe food shortages[6]. Following the genocide, international donors flooded the war-torn country with aid money hoping to rebuild, much of which targeted projects working to address food insecurity. Rwanda has since pursued a set of policies to address food insecurity in Kigali and throughout the country, such as the Strategic Plan for Transformation of Agriculture (PSTA) and the Kigali Conceptual Master Plan (KCMP) [2].

Kigali currently stands as an attractive and growing cultural, economic, and transport hub, home to an estimated 750,000 people[7]. Since the end of the genocide, mass migration of Rwandans from rural areas, the return of many who fled during the genocide, along with the immigration of refugees from neighboring conflict countries has resulted in an unprecedented rate of urbanization[6]. This rapid urbanization has put pressure on living and agricultural spaces in Kigali.

As urban spaces have become more densely populated, rising house prices have pushed the poor out of the city and forced them to build temporary housing on the arable land, reducing the amount of land available for food production. Out of date tools and farming techniques, as well as climate change, have impacted agricultural production significantly. The lack of fertilizer and food storage infrastructure increase the importance of seasonal agriculture, reinforcing the dependency on rain, which fluctuates significantly with a changing climate. When a season yields less than expected, prices skyrocket, further impeding access to food for the lower classes. The lack of irrigation means a season with little rain can quickly result in a famine.

Case Study: Kigali and PSTA

The Rwandan government’s recent agricultural policies have encouraged farmers to grow food staples - instead of growing cash crops for the export market, allocated investment for agriculture technology and food distribution infrastructure in an effort to reduce poverty[2]. While many challenges remain, Kigali today is hailed by the UN as a “modern, model city”, and is recognized as one of the most food-secure cities in Africa[9].

In 1994, the Rwandan Patriotic Front political party took control of the Rwandan government following the end of the genocide, finding the country with a mostly non-functional agricultural sector. Acknowledging the food security crisis, the Ministry of Agriculture and Animal Resources (MINAGRI) developed a plan in 2004 designed to address the deficiencies in the agricultural sector across the nation[2]. This plan, the Strategic Plan of the Transformation of Agriculture Phase I (PSTA), was implemented in 2004 and has continued to evolve. Most recently, a fourth phase was introduced, planning for improvements through 2024[10]. Because agriculture forms such a large part of Rwanda’s economy, contributing about 39% of Rwanda’s GDP and employing about 88% of the active population, the policy’s strategy involves a heavy focus on economic reforms designed to reduce poverty, sustain economic growth, and improve productivity[10]. The second phase of the PSTA concentrated efforts on improving agricultural output and farmers’ compensation. The third phase focused on shifting the country’s agricultural sector from subsistence farming to one based on trade[2]. Commercialization of the agricultural sector has the potential to improve urban food access[11].

This plan has brought improvements in food production and food security, especially in Kigali, by transferring production capacity from traditional export crops such as tea and coffee to staple foods which can be used to feed the population. The plan also allocates resources to agriculture, and shifts away from a leadership model built around a single, central government, delegating more responsibilities to individual districts. From 2007 to 2012 the agricultural sector experienced a 5.4% growth rate which allowed for an increase in domestic food production and reduced the country’s dependency on food imports. The country has seen a significant reduction in the poverty rate, dropping 14% over a 6 year period as a result of these interventions[12]. Agricultural productivity has increased with additional access to post-harvest storage infrastructure, allowing households to store food for longer and avoid seasonal food insecurity. Furthermore, the strategic plan has resulted in more sustainable land management and better utilization of agricultural inputs. The “One cow per household” and “One cup per child” programs were implemented, providing the poorest populations with better access to food[10]. The Food Security Information System was developed to help collect data on the nature of food security in the country, and the Nutrition Action Plan was created to diversify food production, increase kitchen-to-garden activities, and promote nutrition related-knowledge.

Regardless, Rwanda still struggles with food security. Climate change and a lack of agricultural land still pose a major threat to food security in the country. Although the plan assumes farmers can survive during droughts with new irrigation techniques, many are still struggling. Ensuring farmers are properly trained about these techniques and resources is critical to their success[12]. Agricultural productivity could also be improved by using different fertilizers that are more appropriate for specific soils, but many farmers argue that this lacks sufficient research, and providing farmers with strategies and support for disease outbreaks which significantly impact their productivity[13].

Much of the food consumed by Kigali is brought to the city from rural farms. A new strategy, urban agriculture, also has the potential to help feed the city. Urban agriculture has the advantage of being located near where it is consumed, eliminating most of the costs introduced by the food distribution infrastructure. City dwellers are also able to engage more with the production of their food, giving the community more choice about what they eat. In 2009, the Kigali City Council integrated urban agriculture into the Kigali City Master Plan, following the recommendation of the FAO[14].

Overall, these action plans have largely focused on the overarching goal of promoting economic development through improvements in agricultural productivity. It is believed that this will help eliminate food insecurity by providing more citizens the economic means to purchase the food they need. While this is important, supply problems caused by droughts, land scarcity, limited infrastructure, and diseases must also be overcome to provide a sufficient food supply for the entire country[11].

Lessons Learned

Kigali has demonstrated that centralized policymaking, political persistence, and international donor support can help to ensure urban modernization and food security for its citizens within an extremely complex post-genocidal context. The main factors that determine urban dwellers access to food include macroeconomic policies, markets and food prices, employment, and urban agriculture[4]. A country facing Rwanda’s urbanization trajectory and mounting population pressure needs cities that advocate for all people politically and provide new economic opportunities for the poor.

Donor relations and domestic politics (i.e. the consolidation of political power, locally and nationally, by the RPF) has allowed the country’s leaders to design and implement an urban vision of their choosing in a relatively unconstrained manner[9]. In other post-conflict countries, this type of radical urban reorganization can be hindered by institutional conflict or fragmentation, like when governments have less leverage compared with aid donors or opposition parties have power at the city level.

Policymakers must focus their efforts on social policy reform, such as expanding food assistance and income assistance programs, in order greatly diminish food insecurity in Kigali. To ensure an even consensus on goals, issues, and solutions, it is imperative that all stakeholders in the dialogue are encouraged to participate in the creation of national strategies. Improving food security requires addressing the unique factors that contribute to urban poverty, as well as improving access to basic services, market development, and management of natural resources[6].

Through many governmental initiatives, such as the KCMP and the PSTA, food has become more accessible in Kigali. However, so long as fundamental fragility underpins the political system and the development vision for the city neglects those with low incomes, Kigali’s exemplary levels of food security and social stability should not be taken for granted.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Food and Agriculture Organization (2014). Building a Common Vision for Sustainable Food and Agriculture – Principles and Approaches. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, pp.4-12. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3940e.pdf

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 International Fund for Agricultural Development (2012). Country Programme Evaluation. International Fund for Agricultural Development, pp.1-20. Available at:https://www.ifad.org/documents/38714182/39713298/rwanda.pdf/40a18f20-8cd2-435-8731-09404a1f8ab9 [Accessed 11 Mar. 2018].

- ↑ The New Times. (2018). Backyard farming: The untapped cash cow in urban areas. [online] Available at: http://www.newtimes.co.rw/section/read/191026 [Accessed 9 Apr. 2018].

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Armar-Klemesu, M. (2000). Urban Agriculture and Food Security, Nutrition, and Health. Growing Cities, Growing Food, Urban Agriculture on Policy Agenda, pp.99-117. [Accessed 2 April 2018]

- ↑ Guo, B. (2010). Household Assets and Food Security: Evidence from the Survey of Program Dynamics. Journal Of Family And Economic Issues, 32(1), 98-110. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10834-010-9194-3

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Food and Agriculture Organization (2007). Conflict, agriculture and food security. Food and Agriculture Organization. Available at: http://www.fao.org/docrep/x4400e/x4400e07.htm

- ↑ World Population Review (2018). Available at: http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/rwanda-population/cities/ [Accessed 5 Apr. 2018].

- ↑ The New Times. (2018). Private sector urged to venture into agriculture. [online] Available at: http://www.newtimes.co.rw/section/read/213619 [Accessed 9 Apr. 2018].

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Goodfellow, T. and Smith, A. (2013). From Urban Catastrophe to ‘Model’ City? Politics, Security and Development in Post-conflict Kigali. Urban Studies, [online] 50(15), pp.3185-3202. Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/doi/full/10.1177/0042098013487776 [Accessed 12 Feb. 2018].

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Bazivamo, C. (2009). National Agriculture Extension Strategy. Ministry of Agriculture and Animal Resources, pp. 5-27. [Accessed 15 Mar 2018].

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 World Bank (2014). Rwanda - Third Phase of the Transformation of Agriculture Sector Program-for-Results Project. World Bank Group. Available at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/339491468106157439/Rwanda-Third-Phase-of-the-Transformation-of-Agriculture-Sector-Program-for-Results-Project

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Tumwebaze, P. (2018). Rwanda’s agric transformation journey from 2007 to 2017. The New Times. Available at: http://www.newtimes.co.rw/section/read/226975. [Accessed 17 Mar 2018]

- ↑ Ntirenganya, E., (2017). Experts want research and technology to drive up agriculture transformation. The New Times. Available at: http://www.newtimes.co.rw/section/read/217915. [Accessed Mar 28 2018].

- ↑ The Electronic Hallway. (2018). Kigali, Rwanda: Urban Agriculture for Food Security?. [online] Available at: https://hallway.evans.washington.edu/cases/details/kigali-rwanda-urban-agriculture-food-security [Accessed 9 Apr. 2018].