Course:GEOG350/2010WT2/Strathcona Vancouver

GROUP 5: Julia Dullien, Mark Matkowski, Esme Sang, Andrew Yoo, Zachary.

STRATHCONA VANCOUVER

Introduction

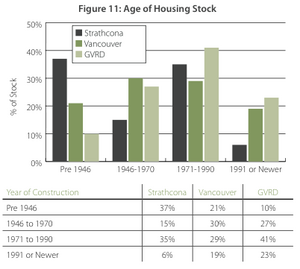

Strathcona is Vancouver’s oldest residential neighborhood, consisting of the largest concentrations of 19th and early 20th century buildings in Vancouver (Community of Vancouver [COV], 2009). It is a part of the Downtown Eastside, composed of the area between Chinatown’s Gore Avenue on the west and Clark Drive on the east; the Burrard Inlet waterfront on the north and False Creek Flats’ Malkin Street on the south (Strathcona Residents’ Association [SRA], 2010). The neighborhood is culturally and ethnically diverse, but over the decades it has also attracted a diversity of negative social and urban issues. Yet, we have found that there is a wealth of services, mostly not for profit, available to those in the area struggling through the grind of everyday life in Strathcona and the Downtown Eastside. On this Wikipage, we will provide a background of Strathcona – its history, features, and significant demographics – in order to proceed into a discussion concerning those public services. Looking at Strathcona via these services provides a good space for reflection on what it exactly is that is hindering or uplifting the neighborhood, what people are actively doing for each other and the streets, and what forces are affecting the services themselves and their outreach to the community.

History

In 1865, Captain Edward Stamp established Hastings Mill, which spurred the growth of a small community surrounding it (SRA, 2010). From it’s beginning, Strathcona has been a working class neighborhood, with a median household income of $15,558 (Lynch, 2011). Just over half of the population live in low-income households (Lynch, 2011). In 1891, Vancouver’s first school was founded in Strathcona, eventually obtaining the nickname “The League of Nations” due to the diverse ethnicity of the school’s population (SRA, 2010).

Demography

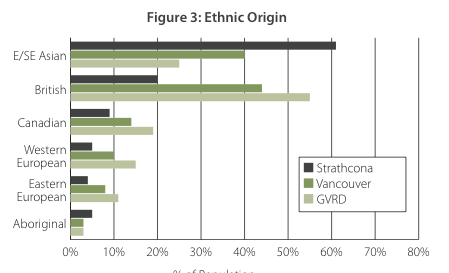

Strathcona is home to immigrants of many diverse ethnicities (including but not limited to the British, Irish, Russians, Croatians, Greeks, Scandinavians, Japanese, and Chinese). As of 2006, Strathcona has a population of 11,920 people (Lynch, 2011). Today, almost 61% of residents in Strathcona claim their dominant language to be Chinese, followed by English at 24% (COV, 2009).

Transportation

Throughout the year 1915, Strathcona was greatly affected by the improvements made to Vancouver’s transportation system. First, the Canadian Pacific Railway came to Vancouver, occupying the eastern one third of False Creek with switchyards, depots, and terminals. Then, the first Georgia Viaduct was built, allowing streetcar service between Main Street and Victoria. In 1950, city planners began to call for major urban renewal and what was known as “slum-clearance” (SRA, 2010). They devised a massive redevelopment plan for Strathcona’s residential area including the construction of a destructive urban freeway that would reshape the area in a drastic fashion. The project was eventually halted due to protest from the community. “These urban highway revolts helped trigger municipal council realignments in which reform councilors gained power to assert local land-use priorities during the 1970s and 1980s” (Canadian Cities in Transition [CCIT] 204). In 1992, the Strathcona Residents’ Association was founded in order to protect the historical community from “insensitive redevelopment schemes” and to help improve city planning. Additionally, projects such as the “Downtown Eastside Revitalization Project,” have recently been set in motion in an effort to try and improve the livelihood in Strathcona.

Issues Facing Strathcona & The Importance of Social Services

Enterprising Women Making Art and Atira

This section focuses on an interview conducted by Julia Dullien with Salima Shakoor, a staff member at Enterprising Women Making Art and Atira, two non-profits in Strathcona. Salima completed a degree in Women’s Studies at UBC. The interview focuses on the non-profits themselves, as well as those whom they provide a safe space for: here it is namely women associated with physical and mental abuse, sex work, drug use, HIV/AIDS, and displacement in Strathcona and the Downtown East Side. To end, this section will place the specific concerns brought up in the interview within the wider context of Strathcona and its position in Vancouver.

- In your opinion, why are "women's issues" an issue in Strathcona? Rather, why are Strathcona and the Downtown East Side commonly viewed as a tough place for women? Is this a stereotype? Do you think these are greater issues in Vancouver, and the focusing on the DTES evades women in other areas?

"I am not sure if DTES is a tough place for women. However, in our society women have been systematically/culturally exploited for a long time and an intersection of all forms of discrimination may effect women more than men, so it makes sense that "women only" services exist. DTES is also in many ways part of that wider culture and hence, women still face a greater need to have safe housing and other safe spaces where they can access different services. There is a need to have women's organizations or services in many parts of the city, and DTES is one of those. For me nothing can be more important that someone's life and the DTES has significantly high mortality rates when compared to the rest of the city (I recommend looking here: http://www.catie.ca/catienews.nsf/0714d2194eb52070852563ab006a5ac9/5b4515b705af55d2852571150073f9e4?OpenDocument). It becomes absolutely crucial to address that. Anybody would agree that the quality of life that most people expect or desire is far from what is the reality of DTES, hence the urgency to address the struggles people face in that area. DTES has many Single Resident Occupancy (SRO) hotels which are being managed by different non-profits that work with BC housing but have trained support workers and are open 24/hrs a day to help people who live in these SROs. Most of these are not only for women – all kinds of people have access. However, Atira (a service Salima is connected with: http://www.atira.bc.ca/) manages and runs SROs that only provide housing for women, at times also called “hard-to-house women.” It is housing for women who all have suffered some sort of violence in the past or are struggling with violence at the present. Other organizations, working solely with women, are emergency shelter homes for women and children such as United Way Women's Shelter (http://www.unitedfamilyservices.org/), DTES Women's Centre (http://www.dewc.ca/), and WISH (http://www.wish-vancouver.net/). Atira has both residential programs and non-residential programs. (This is where I come in)."

- That leads me to EWMA and similar services. It seems like a great program. In a nutshell, why does it exist? Who is it geared towards? Do you think it successfully outreaches with the public? In my last question I asked about women in other areas of Vancouver, does EWMA outreach towards them?

“EWMA started because a lot of women living in Atira housing/shelter were making crafts which they then sold for close to nothing on the streets. EWMA started to provide a creative/interactive space for such women and an avenue for them to sell their products at appropriate market value. EWMA does not work with the government at all. EWMA also is only a program for emerging women artists in the DTES who want to make money through selling art. It is not open to anybody who lives in Gastown or Strathcona to come use it, unless they have difficulty working in the mainstream work environment because they feel they face multiple barriers (single mom, substance use, violent relationships, homelessness, disability) to gain or retain employment in such environments. However, EWMA can be accessed by people who may not live in DTES but consider DTES as their community. EWMA is a specialized program that addresses the needs of such women.”

- Who or what hinders/supports these services in terms of outreach?

“So I went to a grant writing workshop and perhaps I could throw in some of what I learnt there. The 3 causes that receive the most grants and donations in Vancouver are organizations that are working on/with 1) religion, 2) health care, 3) education. All the others, which are most of the things/services in DTES, receive very, very little. Services in DTES are mostly for homeless or people who are affected by substance abuse or violence of any kind. (Though, in this project we talk a lot about health care and education in Strathcona.) That is what Atira focuses on: violence and abuse towards women and children. It is very, very difficult to get funding, and right now, all Atira programs are fighting for funds. O One of the most important reasons I think (and kind of what I got from the grant workshop I attended) is that the donors need to relate and understand the need for such services. They want to donate for their health care, their children's' education, or their faith. Drug use is a distant problem and, a lot of times in our society, something which is viewed as a self-inflicted problem for a highly marginalized population, who donors don't know or can't relate to.”

- What is EWMA's role with the government, if any? Do you think there could be more genuine government participation in a public service such as this? How about the community's role as volunteers and workers? Is it easy to get volunteers and qualified workers?

“I do not know how to answer that question about genuine government support; it would be wonderful but is it ever possible? There are many people willing to help and volunteer their time, but I think one problem which I have seen with non-profits is lack of organization, and some of that is due to lack of resources. So there are volunteers, skilled volunteers, but they are not assigned appropriate work, which would keep them interested for a long time. They are assigned tasks like cleaning, organizing, and minding the space. Tasks in which they do not feel are contributing much to the organization or which provide a sense of responsibility. They may not feel they are "helping" the people of DTES. I think most non-profits are so stretched beyond their limits and the people who work in them are so overwhelmed that a lot of times things are not as organized as they should be, turnover rates are high, and when new staff takes over an abandoned position, it's like starting over again.”

[This concludes the end of the interview.]

Salima also mentioned that a government-run agency (not allowed to share much of this information) owns a lot of buildings in the area and that many are under threat. If there are problems with the building (mildew, flooding, broken heating, etc) then residents and tenants are afraid to ask the government for help because of the very high possibility that they will be kicked out and the building will be rented at a much higher price.

Matt Hern, an Urban Studies lecturer at SFU and UBC, discusses in his text, “Common Ground in a Liquid City: Essays in Defense of an Urban Future,” Vancouver's reliance on developers and capital in relation to the government with a lot of detail. In general, his book displays a wonderful insight into many aspects of Vancouver through a discourse of Vancouver in comparison to other urban environments, or what Vancouver can learn from other cities (e.g., crime in New York, aquaculture in Kuanakakai, regulation in Montreal). Throughout, Hern repeats something along the lines of "I want a self-governed city that can rise beyond disciplinary institutions and governmentality – a city run by citizens, not experts" (Hern 12). He refers to neo-liberalism and capitalist ideologies as being destructive to such an ideal of urban life, referring to Vancouver as an emerging "Dual City." By this, he and other urban scholars mean "…an urban formation precipitated by the new, globalized information economies. Cities have always had different classes living in relative proximity, but in neo-liberal informational economies something more akin to two entirely separate categories emerge. One is composed of people who are hooked into the ‘space of flows,’ a new digitally-based way of living and generating employment and capital, one that is free-flowing around local constraints and able to move with the same liquidity as their investment portfolios. At the same time, there...[are those]...who do not have the knowledge or skills to profit from digital economies, and these folks are increasingly shut out of the opportunities that neo-liberalism provides" (ibid 14). Hern invites us to look towards the East and the West sides of Cambie and Hastings to see exactly how much of a "dual-city" Vancouver is.

To Hern, "It's just not true that a vibrant, living city is necessarily one where the market is god and capital accumulation is what drives innovation and culture" (Hern 15). Yet, "the city continues to pour its resources and energy into attracting investment, courting high-end tourists, building infrastructure for developers and international trade and doing anything and everything to pimp ourselves out to the highest bidders. But that strategy is unsustainable by definition" (Hern 17). I see much of what Hern has to say in Salima's words. This section began with a focus on women's issues, but clearly it is a greater network of issues. It is all intertwined. Both males and females wish to seek housing in a SRO, but those services themselves are at risk for termination of rent. Salima said she did not know how to answer my question concerning the government, she said how could it ever be possible for a government to have genuine support for such organizations, especially when the government wishes to use that space for building incredibly costly development? "We have to... build meaningful ways to live on this land without destroying it (or its citizens). That has to mean re-imagining this city as self-reliant and constructing a thoughtful re-localization of pretty much everything" (Hern 17). This is especially tricky for the services of Strathcona that rely on the city’s money, which also threatens them. Outreach, then, is especially important if conditions are to change. Salima mentioned how hard it is for services in the DTES to obtain grants because donors cannot relate. Perhaps an intensified level of participation from institutions, such as UBC, in helping that outreach could collapse the distance between donors and those on the street. It costs money and time to conduct fundraisers, advertisements, and training for volunteer work. Yet, if it is from within an educational premise, such as UBC or SFU, then work could be inherent in the grade, in the high tuition for international students, and the high taxes for residents. There is a need to disperse myths of poverty, sex work, decrepitude, and drug use as crime. “It is what is called the Pyrrhic defeat theory: the system needs to keep fighting crime in high-profile ways, but just enough so that it is always a problem in the public's eyes, always a virulent threat, but never solved in any substantial way. By maintaining a certain level of failure while never addressing the root cause of crime, public discontent is always focused at a certain end of the spectrum, and outrageous disparities in wealth and privilege remain obscured” (Hern 161). Displaying the connections between issues, such as health care and women's safety in the DTES, is critical and breaks the “Pyrrhic Defeat Theory.” To just say, "There is a high amount of women afflicted with drug addiction and HIV in the Downtown Eastside," does not attract donors when these women are connected with crime, yet making clear that there is lack of health care and services available to these women, the same health care the donors do fight for, would (as bad as this sounds) help bridge a "dual city."

Enterprising Women Making Art

The Emergency Room & Providing Cultural Space

Strathcona is a neighborhood that is specifically known for its unique character and culture-rich community. As the Strathcona Residents’ Association puts it, “Though of many backgrounds and traditions, and living in varying conditions, the history and special circumstances of our common location, Strathcona, imbues this neighbourhood’s residents with a deep sense of place and pride” (SRA, 2010). Residents are currently fighting certain changes that they fear may threaten or potentially destroy the neighbourhood’s existing identity. Although the evolution or modernization of this increasingly sought-after region may be inevitable, there are certain organizations that are currently working to maintain the nature of Strathcona. Here, I will discuss a specific group that was designed to sustain, as well as stimulate, the artistic personality of Strathcona.

The Emergency Room was a public art space provider first established in January of 2007. Although its existence was short-lived, its impact on the neighborhood of Strathcona was huge in voicing the importance of creating cultural spaces that supported aspiring artists. The Emergency Room was first founded and named by a group of musicians as a temporary solution to the lack of venues willing to cater to the underground music scene in Vancouver. It began by hosting a few public performances in the underground parking lot of the Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design on Granville Island. Shortly thereafter, as common interest in the unique project grew and a cultivation of many more artists and musicians began to take notice, the group sought out a more stable place for rent in the neighbourhood of Strathcona. With the collective work of artists and musicians from within the community, the location was soon renovated from a former fish-processing factory into a warehouse venue. In the summer of 2008, the local media began highlighting performances at the “ER,” and the warehouse quickly became a great sensation. The scene became a place that was not limited to musical performances, but also provided studio space for recording artists, as well as a general workspace and art gallery for creative individuals. The warehouse space was closed down in late 2008 due to lack of security and funding.

The importance of providing public spaces for artists of the Strathcona community to live, work, or be inspired is crucial to the cultural development of the neighbourhood. Recently, as part of Vancouver’s “Great Beginnings Initiative,” the city council approved a $40,000 grant to the Strathcona Community Centre (SCC) to begin the “Princess Avenue Interpretive Walk, Mural, and Art Project.” In the process, the council advised the SCC to hire an art consultant and involve the residents of Strathcona to help develop and install artwork on Princess Avenue “to make the street a more family and children friendly place” (COV, 2009). Although the project will make Princess Avenue a more attractive and appealing area in Strathcona, and I agree that such projects are valuable and admirable, I would argue that with a grant that large, the funding of cultural spaces for artists would benefit the community far more.

In Chapter 15 of Canadian Cities in Transition, author Alison Bain analyzes the process of “Re-Imaging Canadian Cities through Spectacle.” She writes, “In a quest to lure members of the creative class, Canadian cities are remaking themselves as centres of arts and culture and marketing themselves as places that provide stimulation, diversity, and a richness of experience that inspire creativity and innovation” (CCIT 265). In beautifying the streets of Strathcona, the city council, without a doubt, hoped to improve the community as a whole. Bain discusses the city of Toronto as a prime example of city-planners using the “spectacle” strategy to stimulate the economy. However, she argues that, “While such short-term events continue to draw crowds and have increased local cultural awareness… arts communities have argued that city funding would be better spent of capital grants that would allow arts organizations and cultural workers to purchase permanent affordable work space, thus breaking the cycle that displaces them from gentrifying neighbourhoods” (CCIT, 266). She theorizes that “cultural programming” rather than “cultural spectacle” will have a more positive and lasting effect on the city.

As of now, there is a growing interest in providing artists with the quality spaces that they need to support and sustain healthy, vibrant communities. City Council must realize that in addition to bringing art to public spaces, more public spaces should be created for artists. The crucial importance and urgency for this is easily evident in the events, which led to the rise and fall of the Emergency Room in Strathcona. Within a year’s time, the ER project had become so popular and desired, that the overwhelming crowds of artists and community members that it attracted eventually led to its demise.

Strathcona Health Society

Healthcare is an extremely important public service and issue that is unresolved in Strathcona, alike many other low-income communities. The Canadian government pays for about 70% of health-care (a rate that has been steadily decreasing over the years) and citizens are left to cover the remaining 30%. However, in a community like Strathcona, even with a 70% subsidy, paying for health care is still incredibly difficult. In an article titled, “Use of Health Services by the Elderly in Low-Income Communities,” Thomas T. H. Wan (expert of public affairs and health service administration programs), states that “Providing all individuals with equal access to a minimum level of health-care is a complex problem” (Wan 82). Fortunately, special organizations, particularly the Strathcona Health Society, are currently working to help low-income families receive certain medical benefits.

The Strathcona Health Society is a charitable and non-profit society that provides proper dental treatment for those who would not regularly be able to afford it. The main focus of this society is to provide dental services to children; however, they still provide dental services to adults and seniors who are also in need.

The clinic is very thorough in communicating with children as well as parents in order to make sure that there is a very clear understanding of all treatments and procedures. If they are not able to treat their patients, the clinic will provide the parent with all of the finest information and referrals available so that the family may still receive the proper treatment at an affordable price elsewhere. Although the main focus is directed at children, the Strathcona Health Society also offers many benefits for adults and seniors; the clinic promises to offer a 20% discount on all services provided to those without health insurance or dental coverage. The Strathcona Health Society also works to maintain a staff that is capable of speaking to seniors from the neighbourhood in their natural languages, including but not limited to Cantonese and Mandarin. They also provide prevention and dental health information, as well as nutritional counseling, to all clients.

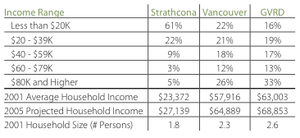

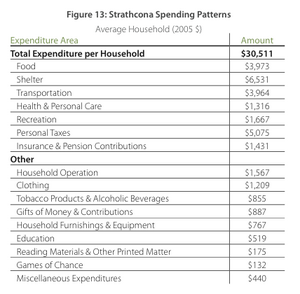

Providing health coverage that satisfies the needs of everyone is extremely complex because of the bridged gap between incomes and certain occupational jobs that offer extended health care. Wan explains, “In the past two decades, a lessening of the gap in health care received by poor and non-poor families has been realized” (Wan 82). Realizing that there is a gap is a positive stepping-stone, but no great change has yet to be implemented. The 30% of health care that Strathconians must pay for is still a struggle, because they do not have sufficient funds to do so. In this regard, the average income of households in Strathcona are relatively lower because of the smaller household size and older age. The average income of the residents in Strathcona is well below $20,000 at an average of 61% of the population (refer to the income graphs). If we compare both the Income graph and the Expenditures graph on the side, it is easy to tell that the majority of the Strathcona population is living in poverty and are barely able to get by with every day expenses, let alone do they have proper funding for healthcare.

In an article in the Vancouver Sun, Lindsay Kines informs the public, “B.C.’s high poverty rate and fractured system of supports for vulnerable families continue to put children – particularly aboriginal children – at risk of an early death, according to a new report from the province’s child watchdog” (Kines, 2011 para. 1). B.C.’s independent representative for children and youth, Ellen Turpel-Lafond, insists that better strategies and province-wide standards must be implemented immediately. “‘Above all,’ she says, ‘we must demand that our government work at all levels, in bold and responsive ways, to address the deep, persistent poverty and life circumstances that inevitably play a constant role in so many of these tragedies’” (Kines, 2011 para. 13).

The Strathcona Health Society only touches bases on assisting with dental services. Although this is great and a good start, there must be another organization or policy brought forward to assist those who need medical attention in hospitals. One solution would be to re-analyze our allocations of public spending and subsidize even more towards health care. Even still, Philip Keefer, a renowned author affiliated with the Economics Research World Bank Group, considers certain difficulties within this concept. “Allocation is often inappropriate, however. Public spending goes to wage bills for bulky state administrations, farm subsidies absorbed by the wealthiest farmers, or public work projects with limited public utility, all at the expense of the quality of public services” (Keefer 3). Therefore, decreasing the amount of public spending on inefficient services might allow us to overcome the complex problem of health care, making it more affordable for those in need.

Providing more affordable health coverage may seem like an inconvenient expense, however, in reality, it must be seen as a tactical investment. “For example, deferred treatment of health problems can bring about enormous suffering and productivity losses, often with cumulative costs far beyond that of the treatment” (CCIT 10). The Strathcona Health Society brings forward a positive light to the community, but it is evident that more must be done in order to help these residents obtain full healthcare protection.

St. James Community Service Society

Homelessness and lack of housing is one of the many problems that the Strathcona neighbourhood and its citizens face. Women, families, and children are among the fastest-growing groups within the homeless population. In Chapter 20 of Canadian Cities in Transition, Dowell Myers argues that, "Housing fits in the middle of everything. It is physical design, it is community economic development, it is social development, it is important to health and educational outcomes, it can be a poverty reduction tool, and it is an investment, a wealth creator and a generator of economic development. It is both an individual and public good" (CCIT 347). The benefits of providing adequate and affordable housing to those in need go much further than simply putting a roof over one’s head. One of the groups attempting to help solve the problem of homelessness and lack of shelter is the St. James Community Service Society. The St. James Community Service Society was established 50 years ago and is a “broad-based social service agency providing care and support today for the most marginalized and vulnerable, while also working to transform communities for the future” (St. James Community Service Society [SJCSS], 2011). St. James provides 52 emergency housing beds in the Downtown Eastside for single women in need of crisis support and for homeless children. Families usually stay between three and six months. Both facilities provide support 24/7 and have dedicated case management teams who help find permanent housing and/or treatment options in order to try and end the cycle of homelessness.

This program has made a noticeable impact on neighbourhoods of the Downtown Eastside in Vancouver, specifically on Strathcona. Over the last year alone the program has had 21 families housed in transitional housing units. More importantly, in 2009, nearly 90% of families graduating from the program secured permanent housing in the community. Also, 41% of women and children from the emergency housing units, whom were supported by St. Jame,s later succeeded in finding permanent housing or other residential treatment programs. In November 2009, the program opened 26 new emergency housing beds in the Downtown Eastside, doubling the capacity in the neighbourhood. There are 66 rooms within a supportive housing residence for vulnerable, older residents (aged 45+) in the Downtown Eastside who are unable to live independently. Ryan Walker and Tom Carter both express the importance of organizations, such as the St. James Community Service Society, which not only work to provide immediate temporary shelter for the homeless, but also work to provide them with real housing options in the future. In fact, they seem to have very strong opinions on the nature of current support systems for the homeless and argue that such programs must aim for more permanent solutions if their true ambition is to eradicate homelessness completely. “Because other types of support, such as for mental health, addiction, or physical health issues, are most ineffective for homeless people, given that being homeless causes such stress and exacerbation of health problems, it is as much as five times more expensive to shelter (in emergency shelters) and treat homeless people than it would be simply to house them properly” (CCIT 347).

One of the main issues causing some residents of Strathcona to be displaced from their homes is gentrification. Gentrification is the process whereby high-income households purchase and upgrade central city housing that once was occupied by residents of a significantly lower income. Canadian Cities in Transition states, “the gentrification of the city by professional classes denies [the working poor] access to housing and services in the core [of the city]” (CCIT 298). Due to its close proximity to Vancouver’s downtown area, Strathcona has seen a significant increase in population over the years. With population increase and the demand to live downtown, city-planners are currently working to intensify the density of inner-city neighbourhoods like Strathcona. Today, some would consider this type of residential upgrading, or the building of new condominium developments in this specific neighborhood, as gentrification. The Strathcona Residents’ Association expresses their concern that “Unsympathetic renovation, demolition, and incompatible new construction could endanger the delicate balance that exists in the neighborhood” (SRA, 2010). Up until recently, housing options in Strathcona have been incredibly diverse. “Strathcona’s residents occupy the entire spectrum from home owners to renters, people who still live in row houses and those who live in apartments, strata and co-ops, and includes people living in assisted and low income housing, and yes, those who are struggling to find a home” (SRA, 2010). Current residents are beginning to witness the effects of this process, including but not limited to social polarization or inequity and an increase in homelessness. Moreover, these effects can influence the health, education, and overall well-being of Strathconians. In describing housing and neighborhood transformation, the textbook states, “Mostly, people want a good home that they can afford and there is evidence to suggest that without one, people’s circumstances relating to health, education, and income security are adversely affected” (CCIT 342). The St. James Community Service Society, along with certain other organizations, as well as community activists, are currently working to help misfortunate citizens of Strathcona cope with these issues.

It seems as if this service is helping the lives of many Strathcona residents, which is what this community is in need of. The main objective for groups such as the St. James Community Service Society is supporting initiatives to comprehensively address homelessness in a way that provides long-term solutions and to develop a resilient and sustainable Downtown Eastside.

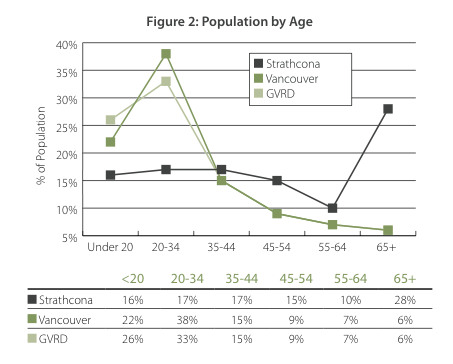

The Britannia Community Service Society

This section will examine services that cater to a specific demographic pertaining to age in Strathcona. It is aimed to achieve a better understanding of the infrastructure within the community and of the problems associated with services that provide for different age groups. Strathcona has a relatively unvaried population when examined through the distribution of people under the age of 65. The average population for age brackets under 65 are roughly 15% each, with the percentage of retirees over 65 being 28%. This suggests that there are a total of 7,390-8,582 people in Strathcona whom are under the average age of retirement (BC Stats, 2006).

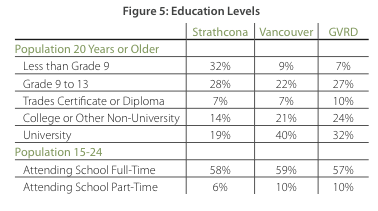

Arguably, the most important aspect of this discussion is education for the demographic age group under 20, which is comprised of 1,907 individuals or 16% of the local population, based on the 2006 census. It is important to understand that there are two main elementary schools available to this demographic in Strathcona – Admiral Seymour Elementary School and Lord Strathcona Elementary School (both provide for grades K-7). These two schools provide an essential service for children in the community; it is they who will have a chance to change the future of local statistics in terms of education and employment. One problem associated with education is that 32% of total adult Strathconians who grew up in Strathcona have only a grade 9 education or lower (Business Improvement Area [BIA], 2006). This problem can be attributed to the fact that these two main feeder schools have only one secondary school for students to continue their education in Strathcona: Britannia Elementary-Secondary. Education in Strathcona is seemingly outdated, with the community housing the oldest elementary and secondary schools in Vancouver. (This idea is supported by examining the overall quality of life for this demographic and the extent of services available to them.) In an article published by The Vancouver Courier, Sandra Thomas explains, “According to research completed by the University of B.C.'s Human Early Learning Partnership, 66 per cent of Strathcona children live in a hostile environment with daily exposure to criminal activity, homelessness, drug abuse, domestic violence social disorder. As well, that same percentage of children from the Strathcona-area near the Downtown Eastside are vulnerable to drop out of school before graduation, consistently fail to achieve the economic security of their peers, fail to meet crucial developmental milestones, lack access to primary health care and face food insecurity” (Thomas, 2010 para. 1-2). While these statistics are staggering, they provide an insight into the problems that this demographic must face throughout their early education. So early, in fact, that the most at-risk group happens to be pre-schoolers. In an article published by the B.C. Teacher’s Federation, Noel Herron explains, “UBC’s Human Early Learning Partnership (HELP), funded by the province, conducts regular assessments of children’s school readiness. This research shows that preschoolers in Strathcona have the highest vulnerability in Vancouver in five criteria: physical health and well-being, language (communication), cognitive skills, social and emotional development, and are not ready for school. An astounding 75% of children in Strathcona are deemed to be at risk. Many of these children (estimated at over 50%) have developmental, health, and support needs that are unmet and result in failure to thrive, failure to achieve developmental milestones, and by the time they reach Grade 3, they have fallen far behind their peers” (Herron, 2009 para. 9-10). These authors and studies suggest a serious problem with the way education is approached in Strathcona. Municipal and provincial aid being scarce, it leaves community members wondering what is being done to mitigate this problem and to provide aid for those citizens that are in need of it. The Britannia Community Service Center Society through Britannia Elementary-Secondary School seems to be the only organization presently working to solve this problem.

Britannia Elementary-Secondary School services a large area of Strathcona and is the only secondary school in the designated school district (Vancouver School Board [VSB], 2011). The school services students K-12, where grade 7 and under are taught in a separate building. The school is a cornerstone for development in Strathcona, even with the drawback of it being the only secondary school in the Strathcona area school district. It is the oldest secondary school in Vancouver but more interestingly, it was amalgamated with Britannia Elementary between 1972 and 1975 – most likely, an attempt at encouraging students to finish high school and promote employment later in life. This was a very crucial time for the school and the citizens of Strathcona in that it also marked the incorporation of the Britannia Community Service Center Society into its elementary-secondary structure. The school provides education to a total of 1800 students in Strathcona (94% of these individuals are under 20) that have complete access to all programs offered through the community services center. The school even has programs in place to facilitate student careers, promote athletics, library resources, community projects and even employment. For example, the students can work at the school store, but only if enrolled in a grade 11/12 marketing classes, which encourages them to continue throughout their education with valuable training and specified education. The school store also has a virtual business model that marketing and business students can interact with, specializing in areas such retail, personal finance, and business management, that is all funded by the Britannia Community Service Center. Through the Community Service Center, students, as well as citizens of Strathcona, can access various aspects of these programs. The center offers adult education for those interested in furthering a career that have not attended post secondary or finished high school. They offer programs in data management, business, information technology and communication (among others) but more importantly, they offer high school equivalency courses in all subject areas to adults of any age. Similarly, they offer a learning program for pre-schoolers, the most vulnerable and high risk individuals of Strathcona. The program is called HIPPY, or Home Instructions for Parents of Preschool Youngsters. It encourages home learning for children up to the age of 6. The activities concentrate on language, discrimination skills, and problem-solving techniques in an effort to better child education, as well as create awareness for parents whom would not normally trust their own strengths as early-child home educators. The efforts of the Community center have been so successful, in fact, that they have opened a program called the Canucks Family Education Center, which is a parent-child program that encourages family literacy and is taught by members of the Vancouver Canucks Hockey team.

While Strathcona has many issues to face in terms of education and at-risk youth, the Britannia Community Service Center Society has drastically changed the way Strathcona approaches education for those with the highest vulnerability. The joint school and community center show that with municipal funding and the addition of public services to a school system, a higher level of education can be reached for students in this demographic. This leads one to suggest that while they are most at risk when considered in the total population, the municipal funding and allocation of social services is not wasted on this demographic. In fact the unemployment rate in Strathcona has shown a marginally slow, but progressive decline since 1980 with the exclusion of economic instability (Stats Can Census Data [SCCD], 2011). Most recently there was a decrease in the local unemployment rate between 2000 and 2008 only to have it almost double during the recession (BC Stats, 2011). Regardless of these statistics, there is no doubt that Strathcona has strength in their services geared towards students under the age of 20. However, it seems that while the Britannia Community Center and school are a great success among families and children in this community, the same amount of time, municipal and provincial funding, and effort need to be implemented in the community to ensure that these youths continue to be taken care of as they leave this demographic. Encouraging post-secondary schools of some kind and continued efforts to create employment for those that are lucky enough to be taken care of under the Britannia Community Center and school becomes of paramount importance if the community is to thrive over time.

Conclusion / Solution

On this page, we have looked at the Strathcona neighborhood by way of some of the services involved in its network. In doing so, the vast array of Strathcona's history and future was brought to the fore, but we could not possibly account for all of this in the page space. So, then, what can be accounted for, what kind of conclusion can we come to from such a small sample of a much larger social problem? How does this speak to Strathcona in particular? As we have seen, there is a host of social programs working to benefit the people of Strathcona. They are designed in a way that gives unique attention to the many Strathconians who are in need, but in that process, they also work to provide solutions to greater social issues that seem to plague nearly every present-day city in Canada, as we know it, in some way or another. Likewise, there is a host of constraints put upon these programs. It seems as if the greater neo-liberal paradigm we learned about from Matt Hern has caught Strathcona and the public services in quite a sticky trap. Something Matt Hern mentions as a possible way to get out of such a trap is to envision a "self-governed city that can rise beyond disciplinary institutions and governmentality - a city run by citizens, not experts" (Hern 12). So the reliance cannot be on the government alone for money, space, and approved programs - individual people of Vancouver need to work together in order to help the services of Strathcona. After all, helping small communities, like Strathcona, to survive and thrive, will only benefit the city of Vancouver as a whole. A greater emphasis on public outreach is crucial. But first of all, the public must be aware that these services exist. The internet is sure to provide such networking, as is artistic visual media, and the involvement of certain institutions, such as UBC, in spreading information about these services and of Strathcona itself.

References

- "BC STATS: Labour and Income." BC STATS: Home. Web. 09 Apr. 2011. <http://www.bcstats.gov.bc.ca/data/lss/labour.asp>.

- "Britannia Community Centre." Britannia Secondary School. Web. 09 Apr. 2011. <http://britannia.vsb.bc.ca/community_centre/community_centre.htm>.

- "Britannia Community Services Centre | How to Find Programs." Something's Happening in Our Community | Britannia Centre. Web. 09 Apr. 2011. <http://www.britanniacentre.org/programs>.

- "Britannia Community Services Centre | Services | Education." Something's Happening in Our Community | Britannia Centre. Web. 09 Apr. 2011. <http://www.britanniacentre.org/services/education.php>.

- Britannia Elementary | Home. Web. 09 Apr. 2011. <http://britannia-elem.vsb.bc.ca/>.

- Bunting, Trudi E., Pierre Filion, and Ryan Christopher Walker. Canadian Cities in Transition: New Directions in the Twenty-first Century. Don Mills, Ont.: Oxford UP, 2010. Print.

- Canucks Family Education Centre. Web. 09 Apr. 2011. <http://www.cfecbc.ca/index.htm>.

- Canadian Medical Association Journal - February 10, 2011. Web. 10 Feb. 2011. <http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/reprint/159/4/388>.

- "Democracy, Public Expenditures, and the Poor: Understanding Political Incentives for Providing Public Services — WORLD BANK." Oxford Journals | Social Sciences | World Bank Research Observer. Web. 10 Feb. 2011. <http://wbro.oxfordjournals.org/content/20/1/1.abstract>.

- "Downtown Eastside Revitalization." City of Vancouver. Web. 10 Apr. 2011. <http://vancouver.ca/commsvcs/planning/dtes/strathcona.htm>.

- "Health Care in Canada." Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Web. 10 Feb. 2011. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Health_care_in_Canada#Government_involvement>.

- Hern, Matt Common Ground in a Liquid City. Oakland, CA: AK Press. 2010. "Interview with Salima Shakoor, of EWMA." E-mail. 10 Feb. 2011.

- Herron, Noel. "BCTF Inner-city Children in Crisis." Web. 10 Feb. 2011. <http://bctf.ca/publications/NewsmagArticle.aspx?id=19514>.

- "History of Britannia." Britannia Secondary School. Web. 09 Apr. 2011. <http://britannia.vsb.bc.ca/about_britannia/history.htm>.

- Inc., Tugboat Media. "About SJCSS | St. James Community Service Society." Latest News | St. James Community Service Society. Web. 09 Apr. 2011. <http://www.sjcss.com/about-sjcss>.

- Kines, Lindsay. "Poverty, Fractured Systems Put B.C. Kids at Risk: Advocate." The Vancouver Sun 28 Jan. 2011, Final ed., sec. A: 6. Print.

- Lee, Jeff. “Council Efforts to Quiet Opposition Meet with Opposition from Community Activists.” Vancouver Sun. 21 Jan. 2011. Web. 11 Feb. 2011. <http://www.vancouversun.com/news/Council efforts quiet opposition meet with opposition from community activists/4142687/story.html>.

- "Lord Strathcona Elementary School." Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Web. 09 Apr. 2011. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lord_Strathcona_Elementary_School>.

- Lynch, Dana. "Vancouver's Strathcona Neighbourhood - Profile of Vancouver's Strathcona Neighbourhood." Vancouver, BC. Web. 10 Feb. 2011.

<http://vancouver.about.com/od/neighbourhoodshousing/p/strathcona.htm>.

- "Schools." Vancouver School Board. Web. 09 Apr. 2011. <http://www.vsb.bc.ca/schools>.

- Shakoor, Salima. "ATIRA, EWMA, and the DTEW." E-mail interview. 11 Feb. 2011.

- "Strathcona's Profile." BizMap BC - Vancouver Market Area Profiles. 2006. Web. 10 Feb. 2011. <http://www.bizmapbc.com/>.

- "Strathcona's Profile." Strathcona Elementary School. Web. 10 Feb. 2011. <http://strathcona.vsb.bc.ca/profile.html>.

- "The Emergency Room." Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Web. 10 Apr. 2011. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Emergency_Room>.

- Thomas, Sandra. "Centre Targets Vulnerable Strathcona Kids." Vancouver Courier. Web. 10 Feb. 2011. <http://www.vancourier.com/sports/Centre targetsvulnerableStrathconakids/3746159/story.html>.

- "Vancouver - CommunityWEBpages - Strathcona." City of Vancouver. Web. 10 Feb. 2011. <http://vancouver.ca/community_profiles/strathcona/index.htm>.

- Welcome to Strathcona, | Strathcona Residents' Association | Vancouver BC. Web. 10 Feb. 2011. <http://strathcona-residents.org/>.

- "Who We Treat - Strathcona Community Dental Clinic Website." Non-profit Community Dental Clinic Focus on Serving Families in Vancouver - Strathcona Community Dental Clinic. Web. 10 Apr. 2011. <http://www.strathcona-health.ca/whowetreat.asp>.