Course:GEOG350/2010WT2/Gastown

Gastown

Overview of the neighborhood

Boundaries

North: Geographically, the waterfront of the Burrard Inlet is the northern boundary of Gastown; physically, however the railway heading westbound towards Waterfront station bars any further development north.

West: The gate which provides the western boundary of Gastown is located parallel to Granville Street at Cordova. This boundary is just west of Waterfront Station.

South: West Hastings street, from Granville street to Main street, is the southern boundary.

East: The eastern boundary as defined by municipal electoral district and in the Vancouver census is Main Street (Dobson).

History

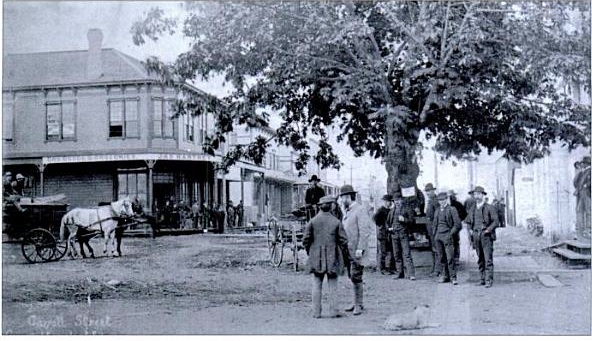

Gastown was established as British Columbia’s first township in 1867 (Gastown) – the same year Canada confederated as a nation. The area was designated as such because it was the vertex where timber could be brought in via the Burrard Inlet and be transported by the national railway (Wyse and Vogel)– which located the terminus station in Gastown proper. From the inception of Gastown it has been a cultural center having since been a hub of restaurants and ‘watering holes’. ‘Gassy Jack’ Deighton, who is immortalized in Maple Tree Square (where Alexander, Powell, Carrall, and Water streets intersect), brought in the first barrel of whiskey into the township for the mill workers and also fathered the provinces first saloon (Wyse and Vogel).

In 1886, just after being incorporated into the greater City of Vancouver, a brushfire destroyed all but 2 of Vancouver’s 400 buildings (Welcome...). Through to the 1920’s Gastown saw a revival in building and infrastructure. It was during this time that most of the buildings that are now declared Heritage buildings were constructed. Many of which are of Edwardian and Italianate architecture (Gastown). The iconic Woodward’s Department store was built in 1903 and was Vancouver’s first vision of the traditional European department store such as the Bon Marche in Paris (Woodward).

From the 1920’s through the Great Depression of the 30’s Gastown became the center of Vancouver’s stereotypical skid row (Dobson). At the height of the population and capital exodus towards the suburbs, the Woodward’s saw a drastic decline in business and so did many of the cultural hubs such as theatres and bars for which Gastown was known (Woodward). With growing talks within the city of demolishing the area, the cities citizens rallied behind the iconic architecture and aesthetic beauty of the area; for which it was declared in Heritage status in 1971 (Gastown). The east side of Vancouver, largely concentrated in Gastown further degraded socially. This area has long been known for its concentration of drug use and petty crime. It is for this reason that the city has concentrated many of the public housing efforts in this area (Dobson). This spiral towards deep poverty culminated when the Woodward’s department store declared bankruptcy in 1993, after which the building was abandoned and commandeered by many of the cities homeless (Mackie).

Through the 1990’s to today Vancouver has experienced a resurgence in the residential appeal of Downtown. The exponential development seen in neighborhoods such as Yaletown and Kitsilano was largely delayed in Gastown because of many social barriers. The great appeal of the aesthetics of the heritage structures, proximity to the CBD, transportation, and waterfront had been outweighed by the proximity to industrial sites such as the Port of Vancouver as well as the poverty culture marked by high crime levels and a disruptive street life (Mackie).

The early stages of the neighborhood gentrification occurred in the late 90’s and early 2000’s when the area was appropriated by many artists and service industry entrepreneurs (Dobson). Assisted by the huge success of the gentrification in Yaletown – there has been a dramatic resurgence of investment in Gastown (Mackie). The success of the neighborhood can again be seen through the rebuilding of the Woodward’s complex (demolished in 2006). After changing ownership several times (2 of these owners were the Province of British Columbia and the City of Vancouver), the Woodward’s site is now the icon of Gastown gentrification (Mackie). It is the largest residential site in the neighborhood as well as it’s only major grocery store, drug store, and it’s largest community center. Though, there are still factors resisting the gentrification of Gastown, the neighborhood is now considered to be a hub of tourism, culture, and of youth in the city (Mackie).

Demography

Total population 79,140; 54% men; 46% women.

Residential Area: 5.6sq km

Average age 20-34; there are statistically fewer families in Gastown than the whole of Vancouver.

Between the years of 2001 and 2006 the population increased by 15.8%, drastically higher then that of Vancouver (5.9%) and Metro Vancouver (6.8%).

The population of Gastown is primarily of English speaking, of Anglo-Canadian origin.

The average income of a Gastown resident is $56,495/year; this is reflective of the fact that there is a high concentration of single occupancy dwellings and few families.

There are no single-detached residences, 99% of the residential space is apartments. The average price for a residence in Gastown is $427,573, and on the rise.

(Gastown Bizmap, et.al.)

Transportation

Gastown is near two downtown Skytrain stations (Stadium, and Waterfront), most significant of which is Waterfront. Waterfront station is the terminus station of all major rapid transit in Greater Vancouver: the Expo/Millenium lines, Canada line, Seabus, and Westcoast Express. Gastown is also artierial for many bus routes in the city. The two main commuter busses for university students: the 135 to SFU and the 44 to UBC, run through Gastown. Many downtown commuter busses also run though the neighborhood traveling east down Richards and Granville streets through to the West End and across the Cambie, Granville, and Burrard bridges. All of this accessible public transit is central to appeal of the area to young professionals, students, and artists. There is however few areas for safe and reliable parking. Traffic is also congested along Water street for much of the day. The congestion is in part caused by the narrow cobblestone streets; the narrow and aesthetically pleasing streets do, however, make for an extremely pedestrian friendly area. Powell connects (at a great distance) to the Highway 1 at McGill – but this is far passed the boundaries of Gastown.

Gentrification

What is Gentrification, Who does it Affect, and Why is it an Issue?

The term "gentrification" was first used by sociologist Ruth Glass in 1960 when she noticed an inflow of gentry—a word used to describe a group of people that were seen to be more wealthy and educated than the their fellow working class citizens—who were buying up old town-houses and cottages in particular neighbourhoods in inner-London (Shaw 1697). The defintion as scene used by Neil Smith in 1982, was much more precise:

“By gentrification I mean the process by which working class residential neighbourhoods are rehabilitated by middle class homebuyers, landlords and professional developers. I make the theoretical distinction between gentrification and redevelopment” (Smith 1982).

In the 21st century, this definition has undergone considerable change and has become a word to describe a lifestyle. Modern definitions of gentrification encapsulate so much more. The word itself doesn’t provoke thoughts of a middle-class man doing renovations on a house in an old neighbourhood to make an out- dated home look more modern; it provokes images of an entire neighbourhood being transformed. The word conjures images of transformation from a rundown neighbourhood to a vibrant, restructured geographical space where apartments are completely redone, and new town-houses aren’t only being renovated, but built from the ground up. The word doesn’t only capture housing; it extends to retail markets, consumer outlets, galleries, boutiques, bars and restaurants—places where these gentrifiers,often white-collar workers--with an interest in culture and heritage--can take pleasure in and express their desire and commitment for a more urban lifestlye (Grant and Filion, 309).

Gentrification From a Scholarly Perspective

Some geographers ask why gentrification occurs and view that question from either a ‘cultural’ or ‘capital’ perspective—or in some cases both. David Ley is of the belief that ‘cultural’ reasons or consumer choices lead to gentrification; on the contrary, geographers like Neil Smith, believe that reasons related to ‘capital’ or the economics of land marketing are the causes of gentrification (Atkinson and Bridge 2005, 6).

David Ley, one of the most renowned writers in the gentrification field views ,what he calls, the ‘creative new class’, as one of the primary reasons why gentrification occurs (Ley 1996) as (cited by Shaw 2008, 1704). Ley is a firm believer in the post-industrial theory of gentrification, as seen in his 1980 paper: “Liberal ideology and the post-industrial city.” In this article by David Ley, he argues that post-industrial gentrification has triggered “a new rationale for government allocation of urban land to different land uses.” The post-industrial theory emphasizes that the move to the inner-city is the result of cultural-choice, under certain conditions; conditions such as, according to Shaw (1716), “the quadrupling of oil prices in the early 1970’s, the maturation of the baby boom generation, the perceived blandness of suburban living…the availability of low-cost inner-city housing and its proximity to city offices and places for cultural consumption all combined to create demand for ‘recycled’ inner-city neighbourhoods” (cited in Ley, 1994). These ‘conditions’ were what ultimately, gave rise to the ‘new middle class’—not to be confused with the ‘creative new class.’

This middle class consisted of young, well-off, single-couples, who held jobs in the service sector with advanced professional and managerial status (Ley 1994). According to Warde (1991, 224), this ‘new middle class’, consisting of white-collar workers, were individuals who had a certain ‘taste’ in culture, an appreciation and interest in heritage and “a locally consensual aesthetic” (cited by Shaw 2008). This gave rise to metropolitan and urban planning policy that came to direct the course of the previously industrial-city (Shaw, 1718). In his 1994 paper, “Gentrification and the politics of the new middle class”, David Ley created a subgroup of this ‘new middle class’--a group he called the ‘creative new class’, which he says emerged around 1970, as a “cadre of social and cultural professionals” that had a ‘niche’ for a left-liberal political stance. And in Ley’s 1996 work, “The new middle class and the remaking of the central city”, this group came to include “professionals in the arts, media, and other cultural fields accompanied by pre-professionals (students)” (Ley 1996, 56). Ley associates this ‘creative new class’ with inner-city living and, for this class, it is by way of their lifestyle that they choose to live in the inner-city.

Neil Smith is of the belief that issues related to ‘capital’—or profit--are the reasons for gentrification. In Neil Smith’s 1996 work, he took his ‘capitalistic’ viewpoint and proposed that the poor ‘stole the inner city’: “middle-class pro-urbanism has now been replaced by a desire for revenge on the poor and the socially marginal” (Atkinson and Bridge, 11) as (cited in Smith 1996). Neil Smith attributed central-city decline to the poor. Smith believes that the reinvestment in the inner-city is a revanchist scheme to reclaim what was previously there’s—there’s being the middle-class (Bain, 263) as (cited in Smith 1996).

Neil Smith’s most renowned contribution to gentrification came from his concept called the “rent gap.” In his 1987 work, Smith acknowledges the work of David Ley, saying that Ley’s dismissal of the rent gap as an explanation for gentrification is incorrect: “The problem lies first and foremost not with the rent gap thesis nor with Canadian cities but with Ley's comprehension and operationalization of the concepts of gentrification and rent gap” (Smith, 462). The “rent-gap” is a concept that Neil Smith examined in 1979 in his work “Toward a theory of gentrification.” This theory built on the work done by David Harvey. David Harvey felt that over-accumulation in production processes was an all too common occurrence that opened up investment opportunities in other sectors—like the high-tech and service sector (Shaw 2008, 1716) as (cited in Harvey 1985). A sectoral switch opens a new market; thus, a search for cheaper location—land-- and labour. Depreciation in land value, or ‘devalorisation’, creates an incentive for landowners to invest in new land—‘revalorisation’—as oppose to investing and repairing the current infrastructure (Harvey 1985) as (cited by Shaw 2008, 1716). Smith, in 1979, pointed out that this ‘devalorisation’ of land creates a “cycle of under-maintenance followed by active disinvestment (Shaw 2008, 1716) as (cited in Smith 1979).” Thus, it is this process that prepares this devalorised land for a cycle of revalorisation—or reinvestment- and subsequent gentrification: “It is here that the rent gap appears, defined as ‘a gap between the ground rent actually capitalised with a given land use at a specific location and the ground rent that could potentially be appropriated under a higher and better land use at that location’ (Shaw 2008, 1717) as (cited in Smith and LeFaivre 1984, 50). For Neil Smith, the key aspect of the “rent gap” is that “the whole point of the rent gap theory is not that gentrification occurs in some deterministic fashion where housing costs are lowest, as Ley is proposing, but that it is most likely to occur in areas experiencing a sufficiently large gap between actual and potential land value” (Smith 1987).

Stages of gentrification

In areas where gentrification occurs, there is a visible change in housing tenure, as rental stock decreases while home ownership increases (Shaw, 2008, p. 1697). Previously run-down buildings are revitalized, and the demography of the area gradually changes as it becomes more affluent. Zukin argued that gentrification occurred as former residents of the inner city “attempted to 'recapture the value of place'” (as quoted in Shaw, 2008, p. 1699). Compared to the suburbs, which have a uniform appearance and often lack the cultural diversity of the inner city, older, historic neighbourhoods can be quite appealing to the creative class.

“Stage-typologizing” (Bain, 2010, p. 269) is one way of explaining who gentrifiers are as gentrification progresses. In the first stage -- the marginal stage -- counter-cultural types such as students, artists and other individuals with lower economic status move into the inner city. They live alongside longstanding, working-class residents of the area and very little displacement, if any, occurs. (Rose; van Weeesep, as cited in Shaw, 2008, p. 1704). Marginal gentrifiers are often “non-family groups” (Bain, p.269), so they do not have needs for infrastructure such as schools, nor do they concerns related to family values which could disrupt the status quo of the inner city.

This marginal shift in demographics is somewhat of a catalyst, as the presence of a diverse and culturally progressive group of people in an otherwise run-down and unappealing neighbourhood makes the inner-city primed for a second stage of gentrification. The people involved in the second stage of gentrification are known as “early-gentrifiers” -- members of the cultural class, and generally liberal-minded. They may be looking to purchase property in the inner city as an inexpensive investment, or they may rent (Shaw, p. 1699).

At this point, the neighbourhood which previously seemed dilapidated and hardly noteworthy to the middle class becomes desirable as a place of investment, where inexpensive properties can be bought for cheap by the middle class with the intent to sell later at a maximum profit. This stage is known as “gentrification proper.” This may be then followed by “advanced gentrification” where major commercial investment, redevelopment and displacement of the original residents occurs: original residents they can no longer afford to live in the neighbourhood as land value increases(Bains, pp. 269 - 27).

Designation of historical status in Vancouver and the decline of single residential occupancy (SRO) units

Gastown, along with Chinatown, which are within the broader Downtown Eastside area of Vancouver, was designated as a “protected historic site” in 1971 as outlined by the Archaeological and Historic Sites Protection Act . Levels of government and business owners recognized that the neighbourhood could be turned into a tourist attraction, and wanted to capitalize on its historic nature. This resulted in many revitalization efforts, including rehabilitation of old buildings and new zoning by-laws (Smith, 2003, pp. 497 – 499). The neighbourhood, which has been home to many single room occupancy (SRO) hotels, lost many of these low-cost units as buildings were upgraded. In anticipation of an increase in tourism during the 1986 World's Fair (EXPO 86), and new interest in residential use of the neighbourhood, Gastown lost around 2,000 SROs by the mid-1980s. Many of these inhabitants were elderly, and their displacement can be noted as the proportion of Gastown residents over the age of 65 was cut in half from 22% to 11% between 1986 and 1996. Compared to the Downtown Eastside as a whole, Gastown's population was younger and was seeing its home ownership levels increase(Smith, p. 499).

A further issue which resulted in the displacement of longstanding residents was that if building owners wished to upgrade their properties in order to be up to standard with historic area building codes, they would need to increase the amount of rent charged to residents in order to recoup their costs (Smith, p. 501)

Gentrification as an issue in Vancouver and "Revitalization without Displacement"

Gentrification is an interesting topic, because depending on one’s viewpoint, it is, simply put, a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ thing. To many, gentrification is something that a city or neighbourhood should strive for, but what are the downsides and why is it an issue? In Vancouver’s Gastown district, it is the after effects of such ‘revitalization’ projects and areas going through ‘regeneration’—words that go hand in hand with gentrification. As an area becomes gentrified, it is seemingly inevitable that the land within its close proximity will surge in value whilst the negative outcome for the people is even greater: “Rising real estate prices are already resulting in increased rents, conversions and closures of residential hotels (SRO’s), creating a constant flow of displacement and evictions of low-income residents, and consequent homelessness” (Higginson). It is important to note that as gentrification continues to revitalize the neighborhood, the concentration of drug use and petty crime which has been characteristic of Gastown for most of its history has not been alleviated, rather, has been pushed to other Vancouver neighborhoods such as Chinatown and Strathcona (Higginson, et.al).

Geographer David Ley, in his article “Are there limits to gentrification?” points out that the Provincial government ,from 2000 to 2010, introduced a policy in Vancouver known as “Revitilization without Displacement” in Vancouver’s inner city in which social-mixing has been encouraged. The goal is to provide housing for middle-class residents on certain available sites whilst “maintaining the level of affordable housing as new non-market units take up the dwindling SRO stock.” In addition to this, some of the others themes of the “Revitalization without Displacement" project include: “Access to the health, social service, and economic development supports” that residents of the Downtown Eastside need; a good level of safety and security for all-- including lessened street disorder and a reduced drug trade; the creation of “civic facilities and services such as parks, community centres, libraries etc.” in or near the area to meet the needs of the population; and the security of the identity of individual neighbourhoods within the Downtown Eastside (Community Services Group).

The project has been successful, in that, not only did it make notable accomplishments from 2000 to 2010, but it has helped portray which issues need resolving in the current decade. A few, out of numerous accomplishments, made from 2000 to 2010 include: The creation of policy for housing and homelessness: “Homeless Action Plan (June 2005) and the Supportive Housing Strategy (June 2007)”; the development of the Four Pillars Drug Strategy and steps taken in harm reduction through the “expansion of low threshold services for mental health and addictions problems, such as the Health Contact Centre, LifeSkills Centre, and InSite (supervised injection site)”; and the city has “supported United We Can, including regular lane cleaning programs employing local low income resident” (Community Services Group).

Despite steps taken forward in many aspects of life in the Downtown Eastside, some of the issues that have presented themselves throughout the latter-half of the previous decade and into the current decade include: An increase in the number of homeless—with many having mental illness and/or addiction; the “increased housing demand, rising land costs and high construction prices” throughout Vancouver; there is still, largely, a lack of beds and mental health and addiction services for those with mental disorders and those involved in the sex trade; and the difference of opinion between people of the Downtown Eastside community and people working for the city—opinions regarding issues such as “soft conversion of SROs, role and pace of market housing, and the development of low income housing” (Community Services Group).

Numerous plans have been drawn up to continually gentrify the Gastown area. Countless bars, restaurants, and galleries have opened up to transform gastown into what it is today. In the Vancouver downtown east-side and Chinatown, plans have been made to “rezone the entire neighbourhood so that existing lots, including those with existing buildings, can be torn down and replaced by profitable condo towers “(Crompton). Not only this, but plans to raise the height restrictions on numerous buildings in gastown have been proposed—not to mention three further high-rise exemptions for three gastown sites: two of three in which are within a block radius of the highly controversial Woodward’s building (Crompton). Non-governmental organizations like the Carnegie Community Action Project (CCAP) have continually spoken out against the gentrification of Gastown. Current projects like the Concord Pacific development has been verbally attacked on a consistent basis. CCAP project facilitator Alison Higginson has pointed out that “the current rate of new development, in which new condos outstrip social housing 3 to 1, is a grave threat to the neighbourhood.”

Limits to Gentrification in Gastown

Like many parts of the city of Vancouver, Gastown has aspects that contribute to gentrification processes, such as its location, its historic attraction and the appeal of its old building charm. These factors attract wealthy visitors who want to renovate the old homes in the area, adding a modern touch to an old building, creating new shops, boutiques and restaurants in the midst of an older area, and creating a novelty out of a neighborhood. All of these aspects are clear when walking through Gastown, and are sometimes sharply contrasted by surrounding homelessness and run down housing. What may be more important when viewing Gastown as an area undergoing gentrification are the factors of Gastown resisting gentrification.

Gentrification is being resisted in Gastown in multiple ways. Deindustrialization, movement away from the city into suburban areas could aid in a limit of incoming gentrification. To contrast, many believe that the inner city is becoming more popular and trendy, causing an influx of newcomers to areas such as Gastown (Ley, 2008). In this case, there is a limited supply of buildings and areas in Gastown to renovate or rejuvenate. It is a small and dense area already, with many interlocking and close together buildings that will hinder construction. People are seeking out these areas for their charm and aesthetics, so there could be large competition for the land and if the area becomes too renovated, then Gastown will lose it’s appeal to incoming residents. In addition, there are currently not many amenities in Gastown, such as schools and grocery stores, but there is aid for those without homes, in the form of women’s centers and food banks. The limited of proper supply for incoming residents could limit the appeal of an area such as Gastown, resisting Gentrification.

Gastown’s community could also pose as a limit to gentrification, resisting change and refusing to vacate the area. There is a large population residing in the streets and low-income housing in Gastown, and gentrification could mean the removal of low-income housing, amenities needed by the impoverished population, and a movement of this community elsewhere to make room for the wealthy incoming residents. With Gregor Robertson’s plan to end homelessness in Vancouver by 2015 (Robertson, 2011) and the constant renovation of the neighborhood, it could arise that the community of Gastown resists the change and refuses to leave the area to allow the incoming residents (Ley, 2008).

Gentrification in Gastown is limited by available space and amenities, how people do not want to live in extremely impoverished areas (Shaw, 2005) and the community’s negative reaction to the idea of vacating and altering the neighborhood for the benefit of wealthy incoming residents. Although gentrification has already greatly impacted Gastown, the factors impeding this process are imperative, causing problems in the area, a vibrant political debate and deep ethical questions.

Possible Solutions

When exploring possible resolutions for Gastown, one can start by examining characteristics found to impede gentrification, as outlined by Ley and Dobson (Dobson, C., & Ley, D. (2008). These include: lack of older, “historic” housing stock, or aesthetically pleasing new residential stock; poor proximity to cultural attractions such as museums, or to environmental amenities such as a waterfront; existence of severe poverty and high crime rates; and, nearness to industrial sites. With the exception of the high crime and poverty concentrated in the adjacent neighborhood of Oppenheimer (Smith, 2001, P 500), Gastown lacks the above physical characteristics found to impede gentrification, thereby making it an attractive area for redevelopment of old housing stock.

While it is likely not possible to prevent further gentrification, let alone to reverse its existing effects within Gastown, limiting its scope could create a “happy medium” that allows for modern, private residential development projects to thrive without pricing lower-income residents out of the neighborhood.

- Provision of grants: In 1971, the provincial government designated Gastown as a “ protected historic site” which resulted in public funding to help revitalize the neighborhood (Smith, 497). On account of Gastown being Vancouver’s oldest neighborhood, it has a high concentration of century-age buildings, many which must be renovated to brought up to current safety codes, and to satisfy “heritage area” requirements. The cost of upgrading these buildings can be quite expensive, and often owners must increase rents in order to recoup their expenses. Nationally funded rehabilitation grants can help cover the costs and prevent building owners from raising rents (Smith 501). If the city and province want to maintain Gastown’s economic viability as a “heritage area”, making rehabilitation grants accessible could help keep rent rates at more affordable levels in Gastown, while business owners continue to attract revenue from tourism.

- Interruption of the market:From 1953 until 1993, joint Federal-Provincial Government programs funded most non-market housing. With the cancellation of this funding, the City of Vancouver has faced challenges in being able to adequately provide affordable housing to those who need it ("Income mix zoning," 2006-2011). Nevertheless, The municipal government can lobby the provincial or federal government to purchase private property, which takes it off the market and limits the amount of residential units that can be rented or sold at prohibitive prices (Ley and Dobson, p. 2477). By removing some units from the market, new, private developments can still exist and sell or rent housing at the prices they wish while existing alongside affordable housing.

Another option is that City Council allows developers to build at increased densities so long as they set aside a certain amount of units as non-market housing("Income mix zoning," 2006-2011). This type of mixed-zoning allows for private construction projects to remain profitable while taking the burden of construction costs off of the cash-strapped city, and creating tax revenue through sales of private residences.

- Community mobilization: Ley and Dobson have also noted that a local organization, the Downtown Eastside Residents’ Association (DERA), has helped band together members of the community, who together have lobbied various levels of government about their needs for neighborhood rehabilitation, affordable housing, and the effects of gentrification (Ley & Dobson, 2483). The DERA has achieved, among other things, changes to the Residential Tenancy Act (RTA), giving residents of hotels the same rights as residents renting other types of housing; prevented a nearby casino from being built; helped develop or operate hundreds of non-market residential units (“Achievements”). The existence of these types of advocacy organizations allows for members of the community who are at risk of being displaced to organize themselves and work within the community and with various organizations so that they can maintain their livelihoods in a quickly changing neighborhood.

These three suggestions can help support and encourage the livelihoods of long-time residents, business owners and entrepreneurs of Gastown who otherwise would have trouble keeping up their living or operating costs, while simultaneously leaving open the opportunity for private, revenue-raising development of private market housing.

References

Achievements | dera:: making the invisible visible . (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.dera.bc.ca/what-we-do/achievements

Atkinson, Rowland and Bridge. Gentrification in a global context: the new urban colonialism. New York: Digital Printing Press, 2005.

Bain, A. (2010). Re-imaging, re-elevating, and re-placing the urban: the cultural transformation of the inner city in the twenty-first century. In T. Bunting, P. Filion, R. Walker (Eds.), Canadian cities in transition: new direections in the twenty-first century (pp. 262 - 275). Don Mills, ON: Oxford.

Community mobilization in Gastown From:No condos until there’s no homelessness, 2011, DTES Neighbourhood Council.http://dnchome.wordpress.com/2011/01/17/pc17/

Community Services Group. 10 Years of Downtown Eastside Revitalization. Government Planning Department. Vancouver: City of Vancouver, 2009.

Crompton, N. The New Gentrification Package for Vancouver's Downtown Eastside. Carnegie Community Action Project. http://www.rabble.ca/news/2010/01/new-gentrification-package-vancouvers-downtown-eastside.

Dobson, c & Ley, D. (2008). Are there limits to gentrification in Vancouver. Urban Studies, 45(12), Retrieved from

http://usj.sagepub.com/content/45/12/2471.abstract doi: 10.1177/0042098008097103

Gastown. Biz Map. Vancouver Economic Development..

Income mix zoning — Vancouver, British Columbia. (2006-2011). Retrieved from http://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/en/inpr/afhoce/tore/afhoid/pore/usinhopo/usinhopo_006.cfm

Ley, D. (1980). Liberal ideology and the postindustrial city. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 70 (2), pp. 238–258.

Ley, D. (1994). Gentrification and the politics of the new middle class. Environment and Planning D, Society and Space 12, pp. 53–74.

Ley, D. (2008) Are There Limits to Gentrification? The Context of Impeded Gentrification in Vancouver. Urban Studies 12.45: 2471-2498. Sage Journals Online.

Mackie, John. (Dec. 9,2009) "Woodwards comes back to life". The Vancouver Sun. Retrieved from http://www.vancouversun.com/business/Woodward+comes+back+life/2305030/story.html

Robertson, G. (2011) Solving Homelessness, Vision Vancouver. Available at: http://www.visionvancouver.ca/solving-homelessness

Shaw, K. (2005) Local limits to gentrification: implications for a new urban policy, in R. Atkinson and G. Bridge (eds) Gentrification in a global context: the new urban colonialism , London: Routledge

Shaw, K. (2008) Gentrification: What it is, Why it is, and What? Geography Compass 2.5 : 1697- 1728.

Smith, H.A. (2002). Planning, policy and polarisation in Vancouver's downtown eastside. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 94(4), Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1467-9663.00276/abstract doi:10.1111/1467-9663.00276

Smith, Neil. "Gentrification and the Rent Gap." Annals of the Association of the American Geographer (1987): 462-465. Welcome to Gastown. Gastown Business Improvement Society. http://www.gastown.org/contact/index.html

Wyse, Dana and Vogel, Ainsley. Vancouver; A History in Photographs. Heritage House Publishing Company. Surrey, BC. 2009. Retrieved from Google Scholar. http://books.google.ca/books?hl=en&lr=&id=O1PUPDLl8z0C&oi=fnd&pg=PA7&dq=history+of+gastown&ots=GhQSNLCQsU&sig=X4RDE3YweVT22e2x8QLFvgP_E9o#v=onepage&q=history%20of%20gastown&f=false

Woodward Stores Limited. (1992). So much to celebrate: Woodward's 100th anniversary. Woodwards stores.