Bioethics

Bioethics

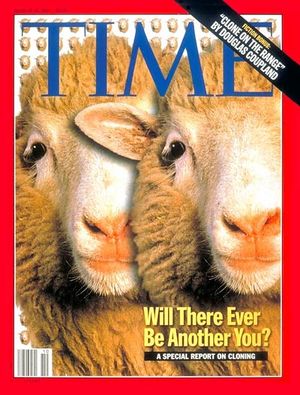

Bioethics is the study of moral and obligational considerations that arise predominantly from the advancement of medical technology and research. Bioethics, however, is not restricted to the field of medicine alone and is considered and debated from multiple fields of discipline. Considered a branch of philosophy, bioethics finds a significant threshold in modern society as the pace of knowledge and technology continues to advance rapidly. Respectively, this pace in technology sparks debates as researches question social implications associated with recent advancements. For instance, the moral considerations in the implications of cloning humans and the resurrection of extinct species has been a source of vehement bioethical debate and contemplation among researchers since the success of Dolly the Sheep in 1996. Moreover, those disciplines that often study bioethics include (but are not limited to) law, politics, literature, psychology, history, pharmaceuticals, nursing, genetics, and biology. A sample of the variety of topics considered by Bioethics that continue to be debated in modern conversation include: abortion, eugenics, alternative medicine, euthanasia, animal rights, [1] and cloning.

History of Bioethics

There is no uniform view on how the field of bioethics began. In historical terms, medical practitioners have had a long standing concern for patients as seen through the Greek Hippocratic Oath or the ancient Indian Charak Samhita. However, the invention of bioethics as a field of study with a focus on incorporating the philosophical and analytical approach to health care has been relatively recent. There are multiple claims to the coining of the term “bioethics”. In 1970 Van Rensselaer Potter an American biological scientist and professor of oncology at the McArdle Laboratory for Cancer Research in association with the University of Wisconsin was the first to use the term in publication. In his original article, Potter describes bioethics as a bride joining the “present and future, nature and culture, science and values, and finally between humankind and nature” [1]. Bioethics to Potter was the means of describing what he saw as a fairly recent emergence of philosophical conscience in the field of life sciences. More generally, Potter sought a greater appreciation for human values in the face of moral dilemmas (this may have been inspired by the atrocities of the Second World War). The term was perpetuated by the creation of the [2] in 1971 by Georgetown University, in which its founder André Helleger chose to call its ethical study of medicine bioethics. Notably, at the same time of Potters and Hellegers’ use of bioethics Hans-Martin Sass- founding member of Germany’s Bochum Zentrum fuer Medizinische Ethik (Bochum Center for Medical Ethics) and Senior Research Scholar Emeritus at the Kennedy Institute of Ethics at Georgetown University, accredits the origin of the word to Fritz Jahr in 1927. Yet, despite the dispute amongst scholars on the origin of the term, it is widely accepted the field became prominent in the United States and spread forth across the globe.

Earlier than the solidification of the field, bioethics can be said to have achieved its prominence largely due to the atrocities achieved through conflict during the Second World War which created an awakening within the scientific community. During World War II, the emergence of the atomic bomb and the use of nuclear weapons on humans began a significant development in how scientific research should be conducted and used. With the approval of the Manhattan project in 1942 by United States president Franklin D. Roosevelt along with the eventual bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, the horrific consequences of scientific research were highly publicized. Prominent activists such as Robert Oppenheimer, a former developer of the atomic bomb, lobbied for the ethical considerations of the use of such destructive technology. Oppenheimer took note of the great destructive force of the atomic bomb and the horrific consequences of radiation burns amongst serious consequences (is now known radiation to be the cause of a myriad of medical problems and deaths within Japanese communities even decades later)[2]. In response to the outcry of ethical considerations for the use of nuclear technology and rallying efforts to create responsible scientists were widely heard. Edward Teller (collaborator of the atomic bomb and father of the hydrogen bomb) narrated the importance of ethic within science when he said,"The important thing in any science is to do the thing that can be done. Scientists naturally have a right and duty to have opinions. But their science gives them no special insight into public affairs. There is a time for scientists…to restrain their opinions least they be taken more seriously than they should be".[3]

Feminist Concerns in Bioethics

The development and scope of bioethics has received extensive criticism from the field of feminist theory. Specifically, the challenges directed expose a shallow regard to the subject of gender in the medical field. Strong articulation for these concerns comes from author Susan M. Wolf who through her publication, “Feminism and Bioethics: Beyond Reproduction” has created a significant voice for feminist input into bioethics. Critique of Wolf’s work by Lisa S. Parker, makes note on the structure of her arguments as they do not reproduce previous arguments or impart that bioethics requires more focus on women. Rather, Parker notes that Wolf’s approach in creating a critique of bioethics as a whole and her call for closer inspection on its components makes for a far stronger case. [4]

In her work, Wolf writes specifically on issues that she sees needs attention in bioethics and feminism as a first step to re-analyzing the field. She notes that though a single cohesive theory or perspective of feminism is non-existent, nonetheless, feminist analysis has much to offer to the field of bioethics. Specifically, Wolf draws on perspectives of Liberal Feminism, advantages of feminist over feminine analysis, use of feminist standpoint theory, bioethics learning from a women’s self-help health movement and Critical Race Theory. Wolf writes that defining the terms within feminism and bioethics is important in understanding the issues within both fields. She points towards a problem with feminist bioethics noting that: Feminist work does not discriminate between the sexes, instead, it contradicts oppression based on gender and indeed male contribution to feminist conversation is important. Another critique of bioethical literature is the notion of only two genders, which Wolf imparts that culturally, biologically and behaviourally indicates more flexibility. Wolf also asks for the consideration of why stereotypes exist for diseases that historically have been ignored in one gender, cardiac illness in women for example, and thus the consideration of gender roles in the creation of medical stereotypes.[5]

Themes in Feminist Bioethics

Continuing the conversation of feminism within bioethics, author Winifred J. Ellenchild Pinch takes the approach that two distinct themes in feminist bioethics exist in which require attention. Her first theme regards the ethics of care (means by which individuals are able to think, reason, and decide about right and wrong), noting that that gender differences in decision making is central to examining moral dilemmas. Pinch’s second theme is the questioning of assumptions of traditional philosophical discourse and the often presented roles for individuals based on gender presumed. Pinch notes that the frequently cited view of women’s roles as biologically and functionally determined centring on sexual, procreative and child rearing activities has oppressive tendencies and is thus morally unacceptable. The goal is then to readdress the imbalances of power and a correction of the biased position of the male as normal and ideal in health care.[6]

Gender in Bioethics

American philosophy professor and bioethicist currently teaching at Michigan State University, Hilde Lindemann observes that the field of bioethics is gendered feminine, but its methods resist the notion which poses a real threat to women. Her notion comes from her observation that among fellow philosophers, bioethics is not held in any particular high esteem, and rather it sits at the bottom of respected philosophical fields. She notes that there exists interesting parallels between bioethics` position in society and the place of women. for instance, those positions within society that hold high esteem are predominately those of males. Lindemann references that in the U.S less than 2% of Fortune 500 companies are lead by women, while 95% of women account for those working as nurses, 75% of those providing long-term care for elderly relatives or friends, and 5.4 million women stayed at home in 2003 to care for children.[7] Lindemann notes this gendered orientation to health care and the notion of prestige reflects in bioethics with more bioethicists identifying themselves with the interests and concerns of doctors rather than other health care workers as physicians hold more social respect. She observes that these skewed power roles reflected in the expectation of gender roles hurts intellectual discourse in bioethics and by effect harms ethical concerns by being trumped by societal norms.

Future of Bioethics

Despite bioethics as a relatively new field many hospitals are developing bioethical committees to incorporate and aid in advising in critical decision making and research. Bioethics continues to grow with increasing post-secondary institutions offering courses or specializations in the field. Schools offering degrees in bioethics include University of Toronto, Queens University, McGill, Dalhousie, and Memorial University of Newfoundland[8] . Currently, a variety of bioethical groups exist to further link the broad study. In Canada, the Canadian Bioethics Society is a national, member-driven, registered charity serving as a forum for individuals interested in sharing ideas relating to bioethics.[9]

World Congress of Bioethics

The 12th World Congress of Bioethics was held in Mexico from June 25 to June 28, 2014. Since its creation the annual convention sets out to focus on the promotion of original findings and new theoretical perspectives surrounding the ethical issues that emerge from the advances of science and technology. Discussions include debates about humans, animals and the environment as a whole.[10] The congress also sets out to discuss cultural differences in what is considered ethical or moral in the context of religion and regional differences.

Other Issues

Controversy

The debate surrounding bioethics often considers the effects of certain health research. Stirring the concern for bioethics were studies and researches that were questionable in regards to their moral ethics. For instance, the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis study that occurred from 1932-1972[11], in which the United States Public Health Service `set out to study the progression of untreated syphilis in rural African American men who thought they were receiving free health care from the government. Initially, the study involved 600 black men of which 201 who did not have the disease. Even when penicillin became the drug of choice for syphilis in 1947, researchers did not offer it to the subjects who for some continued to go untreated. In addition, The 1960`s brought ethical concerns on sending humans to the moon, as well, from 1961-1962, famous researcher[12] was conducting experiments using electrical shocks in order to observe how far participants were willing to go on order to obey orders. These are a few examples that lead to a revision of ethical principles for research in 1964.

Infants Act

Children are not recognized in the Infants Act in BC as being able to make their own medical decisions on the same basis that competent adults are able to make these decision. However, a study that involves diabetes care shows children typically have a high capacity to take control of their health care decisions than what is typically recognized in bioethics. Many people assume that children do not have the capacity to make their own decisions in the way that adults can make them, but there is debate over the legitmacy of this argument. The assumption that children are not mature enough to make these serious decisions is claimed to have been debunked in research. Ultimately, while children should be consulted in their medical conditions, it is accepted by society that the parent is more able to clearly decide what is best for the child.[13]

Bioethics in Health Sciences

Areas of health sciences that are relevant to Bioethics include:

- Abortion

- Alternative Medicine

- Animal Rights

- Artificial Insemination

- Artificial Life

- Artificial Womb

- Assisted Suicide

- Biological Patent

- Bio Piracy

- Body Modification

- Circumcision

- Cloning

- Contraception

- Eugenics

- Faith Healing

- Genetically Modified Organism

- Human Experimentation

- Lobotomy

- Medicalization

- Medical Torture

- Moral Status of Animals

- Nazi Human Experimentation

- Patients Bill of Rights

- Population Control

- Professional Ethics

- Quality of Life (Healthcare)

- Reproductive Rights

- Stem Cell Controversy

- Transexuality

- Vaccination Controversy

References

- ↑ Ten Have, H.,A.M.J. (2012). "Potter's notion of bioethics. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal", 2014,pgs. 59-82

- ↑ H.H. Fawcett, "Effects of A-Bomb radiation on the human body", Journal of Hazardous Materials,Volume 48,Issues 1–3, 2014,pgs. 273–275

- ↑ Life Magazine, issue 1954, 2014, pg.69

- ↑ Lisa S. Parker, "Susan M. Wolf (ed.): Feminism and Bioethics: Beyond Reproduction", Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics, Volume 19, Issue 4,2014, pgs. 411-418

- ↑ Wolf, Susan M., "Feminism and Bioethics : Beyond Reproduction", Oxford University Press, 2014

- ↑ Pinch, Winifred J. Ellenchild. "Feminism and bioethics." Health Reference Center Academica,2014

- ↑ Hilde Lindemann, "Bioethics’ Gender", The American Journal Of Bioethics: AJOB, 2014

- ↑ "Canada Bioethics University Programs",2014

- ↑ "About the Canadian Bioethics Society",Canadian Bioethics Society,2014

- ↑ World Congress of Bioethics, 2014

- ↑ "The Tuskegee Timeline", Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,2014

- ↑ "The Milgram Experiment", Simple Psychology,2014

- ↑ Priscilla Alderson, Katy Sutcliffe, Katherine Curtis,"Children's competence to consent to medical treatment",Hastings Cent Rep, 2014, pgs.25-34

Also See

- American bioethicists Hilde Lindemann and Susan M. Wolf

- Bioethical events going on around the world

- For more information on global bioethics